Yesterday, I attended a book club meeting centered around a popular Chinese book titled <认知觉醒> Cognitive Awakening. Having delved into the first two chapters, I was particularly struck by the book’s insightful exploration of the triune brain model and its profound connection to human behavior.

The author’s clear explanations provided me with a deeper understanding of how our brain’s evolutionary layers influence our actions and emotions. For example, the cognitive brain is likened to a young manager, responsible for planning and decision-making, while the emotional and reptilian brains are compared to two senior staff members who possess their own preferences and agendas—such as gorging on food whenever available, seeking instant gratification, or taking the easy path. This vivid analogy effectively illustrates the internal dynamics and sometimes conflicting motivations that drive our behavior.

However, during our book club discussion, a fellow member raised the point that the triune brain theory might be considered outdated in contemporary neuroscience. Despite this critique, I think that the model retains significant explanatory power when it comes to elucidating common human behaviors.

Notes: Part 1 Introspection, overcome anxiety

Chapter 1: Brain, Anxiety and Patience

- Cognitive ability, emotions, autonomous control develop and mature at different stages; roughly ages 22, 12, 2. Different parts of the brain also had different evolutionary duration. If autonomous brain is 100 years old, then the emotional brain is maybe 55 years old and the cognitive brain may be an infant.

- 80% of the neurons in the cell are part of the emotional and autonomous brain. Only 20% of the neurons are the neocortex. The 80% control critical functions and are supplied with more blood during emergency – causing cognitive brain fog.

- Autonomous and emotional brains have significant processing power at ~11Mbits/sec whereas the cognitive brain has a measly 40 bits/sec.

- For survival, humans needed to prioritize rapid response to danger, immediate gratification (e.g., consumption of food, enjoyment), strong desire for comfort, and energy conservation (thinking, learning, exercising all expend energy). So if we waste time watching Instagram instead of reading, if we eat too much, if we exercise for two days and give up, it’s not that we don’t have enough determination, it’s that the primitive brain has strong evolutionary pressure to behave as if we still live on the Savana.

- The reality is that the cognitive brain rarely have its own beliefs. It’s constantly inventing stories to legitimize what the primitive brain wants. If we want a stronger cognitive brain, we must exercise it and learn to use our natural tendencies to our advantage.

- Anxiety – deadlines, goals, choices, environment, difficult tasks. Want to do too many things and want to see immediate results without too much effort.

- Patience comes from having a longer term view. Accept where we are today, accept slow progress. Let the primitive brain learn the joy of achieving hard things, unleash the power of the primitive brain.

Chapter 2: Unconscious

- The unconscious brain is always working, mostly beyond our conscious awareness.

- Suffering is sometimes easier than solving problems. Real issues are often much smaller problems than we imagine.

- The more clear the goal/target, the easier it is to find a clear path.

- Leverage the power of our unconscious brain’s massive processing power. Tune into the unconscious, pay attention – the most touching, frequent thoughts, first reaction, dreams, body feedback, intuition.

- The most productive place to be in is in stretch zone (what touches you), rather than comfort zone (what the primitive brain wants to do) and difficulty zone (what the cognitive brain wants to do).

[Written by ChatGPT]

An Analytical Essay on the Triune Brain Theory: Evidence, Structural and Functional Differences, and Contemporary Revisions

The human brain, a marvel of biological evolution, has long been a subject of fascination and intensive study. Among various models proposed to explain its complexity, the Triune Brain Theory, introduced by neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean in the 1960s, stands out for its attempt to categorize the brain into three distinct evolutionary layers: the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex. This essay delves into the Triune Brain Theory, examines the evidence supporting it, elucidates the structural and functional distinctions among its three components, and explores recent neuroscientific discoveries necessitating an updated model.

The Triune Brain Theory: An Overview

Paul MacLean’s Triune Brain Theory posits that the human brain comprises three evolutionary stages:

- Reptilian Brain (Basal Ganglia): Representing the most primitive layer, responsible for basic survival functions such as aggression, dominance, territoriality, and ritual displays.

- Paleomammalian Brain (Limbic System): Associated with emotions, memory, and social behaviors, this layer evolved with early mammals.

- Neomammalian Brain (Neocortex): The most recent addition, responsible for higher-order functions like reasoning, language, abstract thought, and conscious decision-making.

MacLean’s model suggested that these layers operate semi-independently, with the older structures governing instinctual behaviors and the neocortex enabling complex cognitive processes.

Supporting Evidence for the Triune Brain Theory

At its inception, the Triune Brain Theory garnered support from various observations and emerging neuroscientific findings:

- Evolutionary Biology: The hierarchical structure of the brain aligned with the evolutionary timeline. Reptilian features were evident in the basal ganglia of mammals, while the limbic system’s emergence corresponded with the evolution of mammals from reptiles. The neocortex, unique to primates, underscored the leap to advanced cognitive abilities.

- Comparative Neuroanatomy: Comparative studies revealed structural differences among species. For instance, reptiles lack a neocortex, which is prominent in mammals, particularly humans. This anatomical distinction supported the idea of layered brain evolution.

- Functional Segregation: MacLean observed that certain behaviors and functions could be localized to specific brain regions. The basal ganglia’s role in motor control and aggression, the limbic system’s involvement in emotions, and the neocortex’s association with reasoning seemed to validate functional segregation.

- Behavioral Studies: Research indicated that damage to specific brain regions led to predictable deficits. Lesions in the basal ganglia affected movement and aggression, while hippocampal damage impaired memory, supporting the association of these structures with their respective functions.

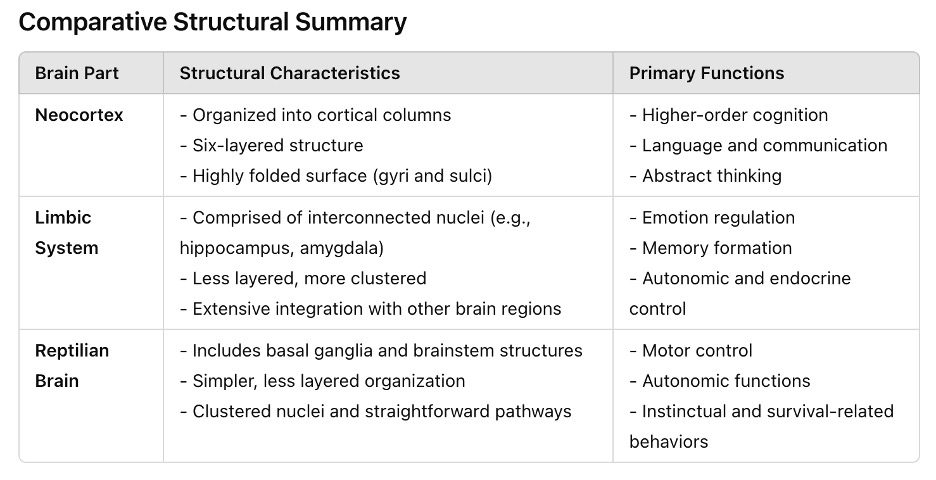

Structural and Functional Differences Among the Three Brain Parts

Understanding the Triune Brain Theory necessitates a detailed exploration of the structural and functional distinctions among its three components:

- Reptilian Brain (Basal Ganglia):

- Structure: Comprising the brainstem and the basal ganglia, this layer includes structures like the medulla, pons, and cerebellum.

- Function: Governs autonomic functions (heartbeat, respiration), motor control, aggression, territoriality, and ritualistic behaviors. It operates largely on instinct, ensuring survival through repetitive and automatic actions.

- Paleomammalian Brain (Limbic System):

- Structure: Encompasses the hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, and hypothalamus.

- Function: Mediates emotions, memory formation, and social interactions. The limbic system enables the processing of complex emotional states, attachment behaviors, and the consolidation of experiences into long-term memory.

- Neomammalian Brain (Neocortex):

- Structure: The outermost layer of the brain, notably the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobes, temporal lobes, and occipital lobes.

- Function: Facilitates higher cognitive functions such as abstract thinking, language, problem-solving, planning, and conscious decision-making. The neocortex allows for nuanced social interactions, cultural development, and technological innovation.

Criticisms and Limitations of the Triune Brain Theory

While the Triune Brain Theory provided a foundational framework for understanding brain evolution and function, it has faced substantial criticism and is considered oversimplified by contemporary neuroscience standards:

- Lack of Evolutionary Accuracy: Modern evolutionary biology indicates that brain evolution is not strictly linear or hierarchical as MacLean proposed. Structures associated with the limbic system and neocortex co-evolved rather than emerging in distinct phases.

- Integration and Interaction: The theory underestimates the complexity of neural integration. Brain regions are highly interconnected, with significant cross-talk between what MacLean categorized as separate layers, challenging the notion of semi-independent operations.

- Neocortex Complexity: The neocortex is not merely an add-on to older structures but interacts dynamically with them. Functions like emotions and memory are deeply integrated with higher-order cognitive processes, contrary to the compartmentalization suggested by the theory.

- Empirical Evidence: Subsequent neuroscientific research has not consistently supported the distinct functional segregation proposed by the Triune Brain Theory. Brain imaging studies reveal that complex behaviors and cognitive functions involve multiple interconnected regions across different “layers.”

New Discoveries and the Need for an Updated Model

Advancements in neuroscience have necessitated revisions to the Triune Brain Theory, emphasizing a more integrated and dynamic understanding of brain function:

- Neuroplasticity: The brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections contradicts the rigid structural divisions proposed by the Triune Brain Theory. Neuroplasticity underscores the brain’s adaptability and the interdependence of its regions.

- Advanced Imaging Techniques: Functional MRI and other imaging technologies have revealed that cognitive and emotional processes engage widespread and overlapping brain networks, challenging the idea of discrete functional layers.

- Genetic and Molecular Insights: Discoveries in genetics and molecular biology illustrate that brain development and function are governed by complex gene-environment interactions, not merely the addition of evolutionary layers.

- Social and Cultural Influences: Contemporary research highlights the profound impact of social interactions and cultural contexts on brain function, suggesting that environmental factors play a crucial role in shaping neural pathways across all brain regions.

- Integrated Models: Modern theories, such as the Connectome project and Dynamic Systems Theory, propose that brain functions arise from the intricate connectivity and dynamic interactions among neurons across all regions, moving away from the compartmentalized view of the Triune Brain Theory.

Towards an Updated Model: A Synthesis of Integration and Complexity

In light of recent discoveries, an updated model of brain function should embrace the complexity and interconnectivity of neural networks. Rather than viewing the brain as a sum of evolutionary layers, it is more accurate to consider it as a highly integrated organ where various regions collaborate seamlessly to produce behavior, cognition, and emotion.

- Network-Based Approaches: Emphasizing neural networks over isolated regions, this perspective acknowledges that functions result from the collective activity of interconnected neurons across the entire brain.

- Hierarchical and Parallel Processing: Modern models recognize that information processing occurs both hierarchically and in parallel, facilitating efficient and flexible responses to environmental demands.

- Embodied Cognition: This approach posits that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body’s interactions with the environment, integrating sensory, motor, and cognitive systems.

- Temporal Dynamics: Understanding the brain’s function requires considering the temporal dynamics of neural activity, including how patterns of activation evolve over time to support complex behaviors.

Conclusion

The Triune Brain Theory provided an influential yet oversimplified framework for understanding the human brain’s evolution and function. While it highlighted the layered nature of brain development and the specialization of different brain regions, subsequent neuroscientific advancements have revealed a more intricate and integrated picture. Modern neuroscience emphasizes the dynamic interactions and interconnectedness of neural networks, moving beyond the compartmentalized view of the Triune Brain Theory. To accommodate new discoveries, contemporary models advocate for a holistic understanding of brain function, recognizing the brain as a complex, adaptable, and unified organ where cognitive and emotional processes emerge from the interplay of numerous interconnected regions. As research progresses, our models must continue to evolve, reflecting the brain’s true complexity and the sophisticated mechanisms underlying human thought, emotion, and behavior.