It’s strange how some questions linger in the mind—like a splinter that occasionally pokes at you. Recently, I was reminded of a question that has haunted me since my high school biology days: How did life begin? It’s one of those exasperating puzzles that is both endlessly fascinating and depressingly unresolvable. Now, thanks to AI, I’ve learned a few new words and concepts that have shed fresh light for me on this enduring mystery.

[Written by ChatGPT]

1. Abiogenesis Theories

Abiogenesis encompasses ideas that life emerged from nonliving chemistry on Earth. Under this umbrella, several specific hypotheses have been proposed:

A. Primordial Soup (Oparin–Haldane Hypothesis)

- Concept:

Early Earth’s reducing atmosphere (rich in methane, ammonia, hydrogen, and water vapor) provided the setting for energy-driven chemical reactions that produced organic molecules. These molecules accumulated in bodies of water (the “primordial soup”) and eventually led to more complex chemistry. - Researchers/History:

- Alexander Oparin and J. B. S. Haldane were the original proponents.

- Modern prebiotic chemistry labs (for example, John Sutherland’s group at the University of Manchester) continue to refine our understanding.

- Evidence:

- The Miller–Urey experiment (1953) demonstrated that amino acids and other organic compounds can be synthesized from simple gases using energy sources like electric sparks.

- Analysis of meteorites, such as the Murchison meteorite, shows that organic molecules are common in extraterrestrial material.

en.wikipedia.org

B. RNA World Hypothesis

- Concept:

The hypothesis proposes that RNA, which can both store genetic information and catalyze chemical reactions (as ribozymes), was the first self‑replicating molecule. Over time, RNA-based systems gave rise to DNA/protein-based life. - Key Researchers:

- Jack Szostak (Harvard University) and John Sutherland (University of Manchester) are among the leaders actively investigating nonenzymatic RNA replication and nucleotide synthesis.

- Gerald Joyce and Michael Yarus also contribute significantly to our understanding of catalytic RNA.

- Evidence:

- Laboratory experiments have shown that RNA can catalyze its own ligation and even promote replication under certain conditions.

- In vitro evolution experiments demonstrate that ribozymes can evolve new functions in the lab.

C. Metabolism‑First Hypotheses

- Concept:

Instead of starting with genetic molecules, these theories posit that self‑sustaining networks of chemical reactions (metabolic cycles) developed first and later gave rise to genetic systems. - Key Researchers:

- Günter Wächtershäuser is one of the primary proponents, proposing the iron‑sulfur world hypothesis (see below) as an example of metabolism‑first.

- Some theoretical work in systems chemistry and network theory (e.g., by Stuart Kauffman) explores autocatalytic sets that could self‐organize.

- Evidence:

- Experiments simulating hydrothermal vent conditions show that iron‑sulfur minerals can catalyze reactions that produce organic molecules.

- Theoretical models of autocatalytic networks have been developed that demonstrate how chemical systems could reach a tipping point toward self‑sustaining metabolism.

D. Lipid World / Protocell Formation

- Concept:

Life may have started when simple lipids self‑assembled into vesicles (protocells), encapsulating organic molecules and providing a microenvironment for chemical reactions to occur. - Key Researchers:

- Jack Szostak (Harvard) and Pier Luigi Luisi (University of Rome) have led experimental efforts to create protocells in the lab.

- Evidence:

- Experiments have demonstrated that fatty acids can spontaneously form vesicles under the right conditions.

- Researchers have shown that such vesicles can encapsulate RNA and other molecules, offering a plausible model for early cell-like structures.

E. Clay Hypothesis

- Concept:

Clay minerals could have acted as catalysts and templates for the assembly of organic molecules, facilitating the polymerization of nucleotides and amino acids. - Key Researcher:

- Graham Cairns-Smith pioneered the idea that clays may have played a role in the origin of life.

- Evidence:

- Laboratory studies indicate that clay surfaces can catalyze the formation of longer organic polymers from monomers.

- The layered structure of clays provides a natural template that might align molecules in a way that promotes bonding.

F. Iron‑Sulfur World / Hydrothermal Vent Hypothesis

- Concept:

Life might have begun at deep-sea hydrothermal vents where chemical energy from geothermal processes and the catalytic action of iron‑sulfur minerals could drive the formation of organic molecules. - Key Researchers:

- Günter Wächtershäuser is best known for this hypothesis.

- Michael Russell and colleagues have provided models and experimental evidence for the vent scenario.

- Evidence:

- Deep-sea hydrothermal vent ecosystems support chemosynthetic life, demonstrating that life can thrive independent of sunlight.

- Experiments replicating vent conditions show that iron‑sulfur compounds can catalyze the synthesis of simple organic molecules.

2. Panspermia Theories

Panspermia moves the question of the origin of life off Earth by suggesting that life—or its building blocks—might be widespread in the cosmos and can be transferred between planets. Variants include:

A. Lithopanspermia

- Concept:

Microbial life can be transferred between planets by being encased in rocks or meteorites ejected from a planetary surface. - Key Researchers:

- Researchers like David Melosh have modeled impact processes and survival probabilities of microorganisms during ejection and re-entry.

- Chandra Wickramasinghe and Fred Hoyle were influential proponents of cosmic panspermia.

- Evidence:

- Meteorites such as those from Mars (e.g., ALH84001) and studies of the Murchison meteorite show that organic compounds are common in space.

- Space exposure experiments (like the Tanpopo mission) have demonstrated that certain microbes can survive for extended periods in space when shielded. princeton.edu en.wikipedia.org

B. Radiopanspermia

- Concept:

Tiny life forms or spores might be propelled through space by radiation pressure from stars. - Key Researchers:

- Svante Arrhenius originally proposed the concept.

- While less emphasized today, some theoretical studies in astrobiology continue to examine the possibility.

- Evidence:

- Calculations and models indicate that if microbes are small enough, radiation pressure could impart sufficient acceleration.

- However, the harshness of radiation also poses a challenge to survival, making this idea less supported by experimental data.

C. Directed Panspermia

- Concept:

Life might have been deliberately spread by an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, seeding planets with microbial life. - Key Researchers:

- Francis Crick and Leslie Orgel famously proposed directed panspermia in the 1970s.

- Though largely speculative, it has been discussed in SETI and astrobiology circles.

- Evidence:

- There is no direct experimental evidence for directed panspermia. It remains a hypothesis that is more often explored in science fiction and philosophical debates than in laboratory work.

D. Molecular (Pseudo-) Panspermia

- Concept:

Instead of whole cells, this theory suggests that space delivers the organic molecules—the building blocks of life—which then help trigger local abiogenesis. - Key Researchers:

- Many of the same researchers involved in prebiotic chemistry (such as those studying meteorite organics) contribute indirectly here.

- Evidence:

- Analysis of cometary and meteoritic material (for example, via the Stardust mission) has repeatedly confirmed that complex organic molecules exist in space. en.wikipedia.org

3. Autocatalytic Set and Network Theories

- Concept:

Rather than a single, “miraculous” event, life may have emerged when a network of molecules began to catalyze each other’s formation in a self‑sustaining cycle. Once an autocatalytic set is established, it can grow and evolve. - Key Researchers:

- Stuart Kauffman is a leading figure in developing the theory of autocatalytic networks.

- Various groups in systems chemistry and synthetic biology are actively exploring these ideas.

- Evidence:

- The Soai reaction is an example of asymmetric autocatalysis in a chemical system, demonstrating how a small imbalance can be amplified.

- Theoretical models and computer simulations have shown that molecular networks can exhibit self‑organization and even rudimentary replication dynamics.

Summary Table

| Theory | Key Proponents/Groups | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Primordial Soup | Oparin, Haldane; John Sutherland’s group | Miller–Urey experiment; meteorite organic analyses |

| RNA World | Jack Szostak, John Sutherland, Gerald Joyce | In vitro RNA replication; ribozyme experiments; laboratory synthesis of ribonucleotides |

| Metabolism‑First | Günter Wächtershäuser; Stuart Kauffman | Experiments simulating vent conditions; theoretical models of autocatalytic networks |

| Lipid World / Protocell Formation | Jack Szostak, Pier Luigi Luisi | Spontaneous formation of fatty acid vesicles; protocell experiments that encapsulate RNA |

| Clay Hypothesis | Graham Cairns-Smith | Laboratory studies showing clay-catalyzed polymerization; templating effects of mineral surfaces |

| Iron‑Sulfur World / Hydrothermal Vent | Günter Wächtershäuser, Michael Russell | Discovery of chemosynthetic communities at hydrothermal vents; laboratory simulations of iron‑sulfur catalysis |

| Lithopanspermia | David Melosh; Chandra Wickramasinghe and Fred Hoyle | Survival studies of microbes in meteorite analogs; analysis of Martian meteorites; space exposure experiments like Tanpopo |

| Radiopanspermia | Svante Arrhenius | Theoretical models; calculations of radiation pressure effects (though challenged by high radiation damage concerns) |

| Directed Panspermia | Francis Crick, Leslie Orgel | Conceptual arguments; speculative discussions within SETI; no direct experimental evidence |

| Molecular (Pseudo-) Panspermia | Many prebiotic chemists (e.g., teams studying the Murchison meteorite) | Analyses of organic compounds in comets and meteorites; Stardust mission findings |

| Autocatalytic Set / Network Theories | Stuart Kauffman; researchers in systems chemistry | Laboratory demonstrations of autocatalysis (e.g., Soai reaction); theoretical models and computer simulations showing self‑organizing chemical networks |

Final Thoughts

Each theory provides a different piece of the puzzle regarding the origin of life. Researchers continue to work on these ideas through laboratory experiments, field studies (like meteorite analysis), theoretical modeling, and space missions. While no single theory currently explains every step from chemistry to biology, together they help us frame the questions and design experiments to test how life might arise under various conditions.

By understanding who is working on each theory and the nature of the supporting evidence, we get a clearer picture of this multifaceted challenge—a puzzle that touches on chemistry, geology, biology, and astronomy.

Are We Extraterrestrial?

There is considerable evidence and a long‐standing hypothesis that materials carrying biological molecules—and even entire microorganisms—can be exchanged between Earth and space. In other words, genetic “ingredients” and possibly even living cells may travel from Earth out into space and vice versa, both in Earth’s early history and continuing today.

Below are the key points:

1. Natural Ejection of Terrestrial Material into Space

Large impact events (from asteroids or comets) on Earth can launch fragments of rock into space—a process known as lithopanspermia. Some of these rocks, if they contained microbial life or organic compounds, might survive the harsh journey through space. Research and simulations have shown that low‐velocity ejecta may be more easily captured by other bodies in the solar system, and indeed, studies have suggested that material ejected from Earth in ancient impacts may have reached the Moon, Mars, or even traveled interstellarly (for example, see the Princeton study discussed in

2. Infall of Extraterrestrial Organic Material

Meteorites, comets, and interplanetary dust continuously bombard Earth. Many meteorites (like the famous Murchison meteorite) have been found to contain a rich assortment of organic molecules—including amino acids, nucleobases, and even sugars—which are the building blocks of genetic material. Although these compounds are not “genetic material” in the strict sense (DNA or RNA), they provide the essential ingredients for life. Moreover, organic molecules synthesized in space may have been delivered to Earth in its early history, contributing to prebiotic chemistry (see also

en.wikipedia.org on the ubiquity of organic compounds in space).

3. The Panspermia Hypothesis

Some researchers (notably Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe) have long argued that life itself—or its genetic precursors—might have originated elsewhere in the cosmos and been “seeded” on Earth via incoming meteoritic material. While still controversial and not part of the mainstream consensus on abiogenesis, the panspermia hypothesis posits that genetic material (or even dormant microbes) could travel between planetary systems (as summarized in

4. Ongoing Evidence from Space Missions

Recent experiments provide further support for the exchange process. For example, the Tanpopo mission on the International Space Station has collected cosmic dust and even exposed terrestrial microorganisms in low Earth orbit. These experiments show that hardy microbes (such as the extremely radiation‐resistant Deinococcus species) can survive the combined effects of vacuum, radiation, and temperature extremes in space for years (see

en.wikipedia.org). This survival capability suggests that if microorganisms are ejected from Earth, they might remain viable long enough to eventually encounter another habitable environment.

5. A Two-Way Street

In summary, the exchange goes both ways:

- Outward from Earth: Impact events eject rocks containing microbes or organic molecules, which can travel through space.

- Inward to Earth: Extraterrestrial bodies (meteoroids, comets, dust) bring organic compounds—and perhaps even intact genetic material—down to Earth.

Although it is still an active area of research whether such exchanges have directly led to the seeding of life (or new genetic diversity) on Earth or elsewhere, the cumulative evidence from astrophysics, laboratory experiments, and space missions supports the notion that Earth is not an isolated “island” but part of a larger, dynamic system in which genetic material is continuously exchanged.

Conclusion:

Genetic material (or its essential building blocks) is indeed exchanged between Earth and space both in the distant past and in ongoing processes. This natural exchange—through meteorite impacts, cosmic dust infall, and even inadvertent contamination from human spacecraft—forms one of the foundations for panspermia theories, which continue to be explored and debated in astrobiology.

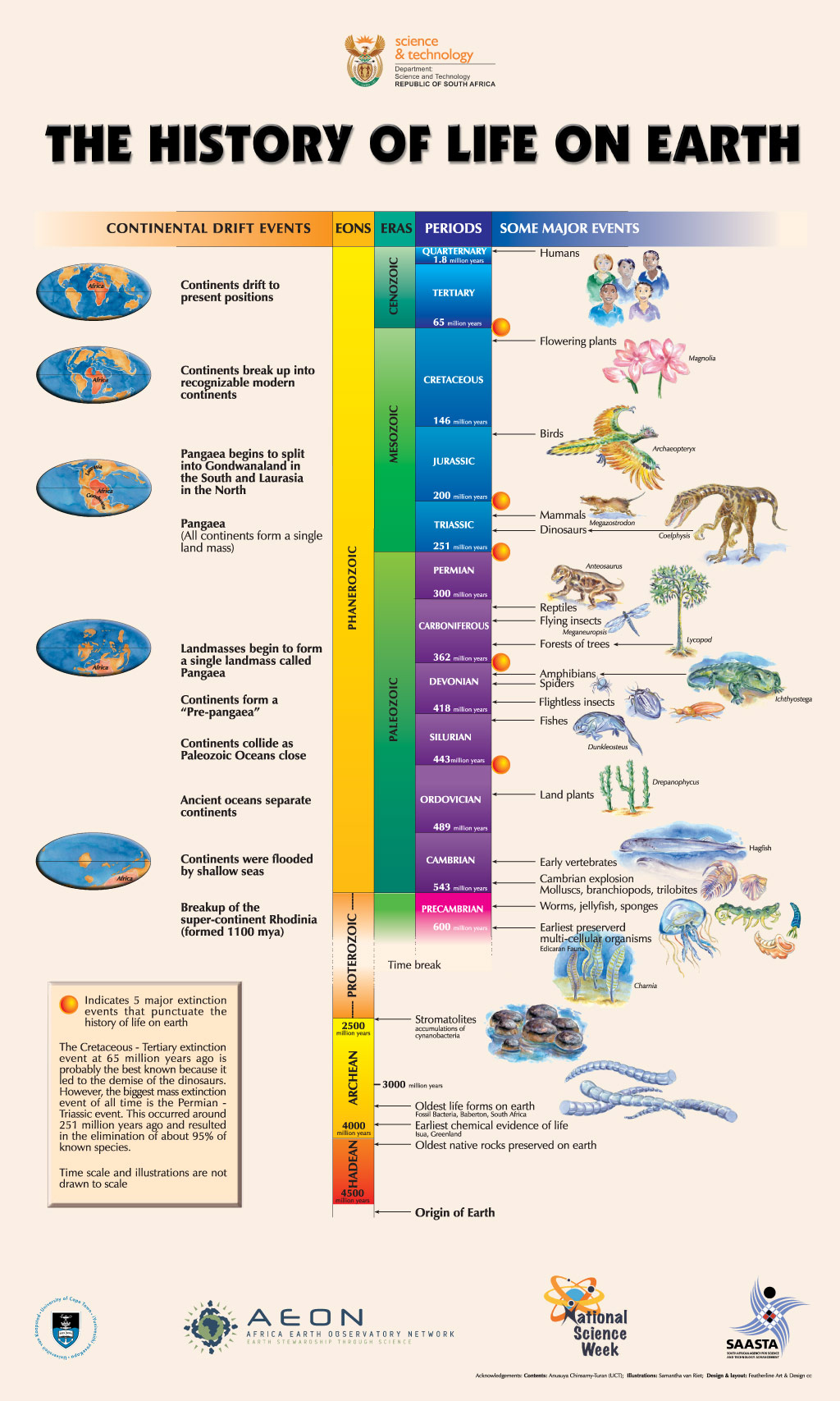

Key Milestones

- 13.8 BYA – Big Bang:

The universe begins in an extremely hot, dense state and then expands and cools. - 13.2 BYA – Formation of the Milky Way:

Our galaxy forms from gas and dust coalescing under gravity. - 4.6 BYA – Formation of the Solar System:

A rotating disk of material forms around the newborn Sun, eventually accreting into planets. - 4.54 BYA – Formation of the Earth:

Earth is assembled through the gradual coalescence of planetesimals. - 4.5 BYA – Formation of the Moon:

A giant impact between Earth and a Mars‑sized body ejects material that coalesces into the Moon. - 4.4 BYA – Emergence of Water on Earth:

Water appears on Earth via volcanic outgassing and impacts from water‑rich comets/asteroids. - 4.0 BYA – Establishment of the Early Atmosphere:

Volcanic outgassing produces an atmosphere that is very different from today’s oxygen‑rich air. - 3.5 BYA – Emergence of LUCA:

The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) appears as a simple, single‑celled organism lacking complex organelles. - 2.0 BYA – Endosymbiotic Event:

Early eukaryotic cells acquire mitochondria through an endosymbiotic event—engulfing an alpha‑proteobacterium—which is key to developing cellular complexity. - 600 MYA – Appearance of Early Multicellular Animals:

The earliest multicellular life begins to appear. - 470 MYA – Emergence of Land Plants:

Primitive plants colonize land, eventually transforming Earth’s surface and atmosphere. - 230 MYA – Dominance of Dinosaurs:

Dinosaurs emerge and dominate terrestrial ecosystems during the Mesozoic Era. - 2.5 MYA – Appearance of Early Humans:

Early members of the genus Homo appear, marking the beginning of our direct evolutionary line. - 300 KYA – Emergence of Homo sapiens:

Modern humans evolve, developing the advanced cognitive abilities and anatomical features we recognize today.