[Written by ChatGPT]

Thinking, Fast and Slow is one of those rare books that changes the way you see the world—and yourself. Written by Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics, the book explores the two ways our minds work: the fast, instinctive side and the slow, thoughtful side. Kahneman walks you through everyday situations—making a choice, judging a person, reacting to a headline—and gently reveals just how often we rely on shortcuts that lead us astray. It’s eye-opening, humbling, and oddly comforting to realize how universal these mental quirks really are.

When the book came out in 2011, it didn’t just land in academic circles—it exploded into boardrooms, classrooms, and living rooms. Its ideas changed how people think about thinking. Marketers, investors, teachers, and policymakers started paying closer attention to how decisions actually happen—not how we wish they did. Concepts like “loss aversion” and “confirmation bias” became part of everyday vocabulary, helping people recognize patterns in themselves and others they’d never noticed before.

What makes Kahneman’s story even more powerful is the deep partnership he had with Amos Tversky, his collaborator and close friend. Together, they challenged the old idea that humans are mostly rational creatures. Kahneman often says the best work of his life was done with Tversky, who passed away before they could share the Nobel. Their work wasn’t just intellectually brilliant—it was rooted in curiosity, generosity, and a real desire to understand what makes us tick. That spirit comes through on every page of Thinking, Fast and Slow, and it’s a big part of why the book continues to resonate with so many people.

Related posts: Cognitive biases, Conscious vs. Unconscious thinking

Part I: Two Systems

This section introduces the central concept of the book: the division of the mind into two modes of thinking—System 1 (fast, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, deliberate).

Chapter 1: The Characters of the Story

- Introduces System 1 (automatic, quick thinking) and System 2 (effortful, conscious reasoning).

- System 1 handles routine tasks and snap judgments; System 2 takes over when logic or focus is required.

- Most decisions are made by System 1, with System 2 endorsing them unless there’s a clear error.

Chapter 2: Attention and Effort

- System 2 thinking requires mental effort and attention, which are limited resources.

- When we’re mentally taxed (e.g., memorizing a number), we rely more on System 1.

- Mental effort is exhausting—this helps explain why people often take cognitive shortcuts.

Chapter 3: The Lazy Controller

- System 2 is “lazy” and often avoids engaging unless absolutely necessary.

- This laziness allows System 1 to dominate, which is efficient but can lead to biases.

- Self-control and cognitive tasks draw from the same mental pool—when one is used, the other weakens.

Chapter 4: The Associative Machine

- System 1 links ideas together automatically via associative memory.

- When you hear a word or see a picture, related concepts get activated instantly.

- This helps us navigate the world efficiently but can also produce false impressions or stereotypes.

Chapter 5: Cognitive Ease

- When things feel easy to understand (fluent, familiar, repeated), we trust them more.

- Cognitive ease = more System 1 processing; cognitive strain = System 2 activation.

- We are more likely to accept ideas as true when they are easier to read, pronounce, or recall.

Chapter 6: Norms, Surprises, and Causes

- System 1 constantly builds and updates mental norms about the world.

- When something violates a norm (a surprise), System 2 may get triggered to reassess.

- We have a strong bias toward interpreting the world in terms of causes and stories, even when randomness is involved.

Chapter 7: A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions

- System 1 is prone to jumping to conclusions with limited evidence.

- It creates coherent stories even from sparse information—this is often useful, but can lead to errors.

- This is the basis of many cognitive biases, like stereotypes or overconfidence.

Chapter 8: How Judgments Happen

- Judgments are often made by substituting a difficult question with an easier one without realizing it.

- System 1 provides quick impressions, and System 2 often just agrees.

- Example: “Is this person competent?” becomes “Do I like them?”

Chapter 9: Answering an Easier Question

- This “attribute substitution” happens when we unconsciously answer a different question than the one asked.

- Especially true for abstract or complex questions (e.g., “How happy are you with your life?” becomes “How happy are you right now?”).

- System 1 simplifies problems automatically and intuitively.

Key Takeaway from Part I:

Humans are not purely rational beings. Our brains rely heavily on the fast, intuitive System 1, and although System 2 is capable of deep thought and logic, it’s often lazy or distracted. Understanding this dual-system model helps explain many of the flaws in our judgment and decision-making.

Part II: Heuristics and Biases

This section explains how System 1 uses mental shortcuts (heuristics) that often lead to biases—systematic errors in judgment.

Chapter 10: The Law of Small Numbers

- People mistakenly believe that small samples represent the whole population.

- This leads to overinterpreting random patterns (e.g., assuming two lucky wins mean skill).

- In truth, small samples are more likely to show extreme outcomes due to chance.

Chapter 11: Anchors

- When people make estimates, they are influenced by arbitrary “anchors”—initial numbers presented to them.

- Even unrelated or random numbers can skew judgments (e.g., spinning a roulette wheel before estimating African nations in the UN).

- System 1 suggests the anchor, and System 2 adjusts—often insufficiently.

Chapter 12: The Science of Availability

- Availability heuristic: People judge frequency or probability based on how easily examples come to mind.

- If you can recall something easily (like shark attacks), you may think it’s more common than it is.

- Media coverage amplifies this effect.

Chapter 13: Availability, Emotion, and Risk

- Emotional events are more vivid and thus more available.

- This leads to distorted risk perception (e.g., fear of flying vs. driving).

- The more dramatic and emotional an event, the more likely people are to overestimate its likelihood.

Chapter 14: Tom W’s Specialty

- Introduces the representativeness heuristic: judging probability based on how much something resembles a stereotype.

- People ignore base rates (statistical realities) in favor of how “typical” someone or something seems.

- Example: Guessing Tom W studies computer science because he fits the “nerdy” stereotype, ignoring actual enrollment statistics.

Chapter 15: Linda: Less is More

- Famous conjunction fallacy experiment: People think it’s more likely Linda is a feminist bank teller than just a bank teller.

- Why? Because her description fits the feminist stereotype.

- But it’s statistically impossible for a subset (feminist bank teller) to be more probable than the broader set (bank teller).

- System 1 loves coherent stories, even at the expense of logic.

Chapter 16: Causes Trump Statistics

- People prefer causal explanations over statistical ones, even when statistics are more reliable.

- We like narratives—they’re easier for System 1 to process.

- This contributes to the neglect of base rates and reliance on “compelling stories.”

Chapter 17: Regression to the Mean

- When something is unusually good or bad, the next measurement is likely to be closer to average.

- People misinterpret this natural regression as being caused by their actions (like a punishment or reward).

- Example: A pilot might wrongly believe that yelling at someone improves performance, when it’s just statistical reversion.

Chapter 18: Taming Intuitive Predictions

- Intuitive predictions are often too extreme, because they ignore statistical realities.

- Kahneman suggests using a three-step process:

- Start with the base rate.

- Adjust based on individual information.

- Resist the urge to over-interpret weak evidence.

- System 2 can intervene to correct System 1’s overconfidence.

Key Takeaway from Part II:

We often rely on shortcuts—like how typical something seems or how easily it comes to mind—to make judgments. These heuristics are efficient but can systematically mislead us. Awareness of these biases is the first step toward better thinking and decision-making.

Part III: Overconfidence

This section focuses on the limits of human intuition, especially among experts, and explores how we often misjudge our knowledge, predictions, and understanding of events.

Chapter 19: The Illusion of Understanding

- People create coherent narratives of past events, believing they were predictable.

- This hindsight bias makes the world seem more predictable than it really is.

- We underestimate the role of luck and randomness in outcomes.

- “What you see is all there is” (WYSIATI): We build stories based only on the information at hand, ignoring what we don’t know.

Chapter 20: The Illusion of Validity

- We tend to be overconfident in our judgments, even when they lack accuracy.

- Confidence comes from the coherence of the story, not its correctness.

- Example: Stock pickers or interviewers may feel certain about their decisions despite poor track records.

Chapter 21: Intuitions vs. Formulas

- Statistical models outperform human judgment in most areas (e.g., predicting success in college, parole decisions).

- People resist algorithms because they trust intuition more, even when data proves otherwise.

- Combining multiple inputs into a simple formula often produces better results.

Chapter 22: Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?

- Expert intuition is only reliable in high-validity environments (e.g., chess, firefighting), where patterns repeat and feedback is quick.

- In low-validity environments (e.g., financial markets, politics), intuition is often flawed.

- Kahneman distinguishes between genuine skill and illusory pattern recognition.

Chapter 23: The Outside View

- Planning fallacy: People underestimate time, cost, and risk in projects.

- Inside view: Based on the specifics of the case; too optimistic.

- Outside view: Uses statistics from similar past cases; more realistic.

- Kahneman recommends adopting the outside view for better predictions.

Chapter 24: The Engine of Capitalism

- Entrepreneurs are often overly optimistic—this drives innovation and economic growth but also high failure rates.

- Optimism is reinforced by WYSIATI and the illusion of control.

- Overconfidence leads to risk-taking, which sometimes pays off (but usually doesn’t).

- Society benefits from this bias—but individuals may pay the price.

Key Takeaway from Part III:

Humans are naturally overconfident in their knowledge, predictions, and control over outcomes. We construct believable stories based on incomplete data and often trust intuition over evidence. Recognizing when to apply the outside view and statistical thinking is crucial for better decisions—especially in uncertain, complex environments.

Part IV: Choices

This section introduces Prospect Theory, Kahneman’s major contribution to behavioral economics, and explores how people evaluate gains and losses irrationally, often violating expected utility theory.

Chapter 25: Bernoulli’s Errors

- Traditional economics (Bernoulli’s theory) assumes rational decision-making and expected utility.

- Kahneman and Tversky found that real-world decisions don’t follow these principles.

- People are more sensitive to changes in wealth than to total wealth—reference points matter.

- Diminishing sensitivity: The subjective value of money decreases as amounts increase (e.g., $100 means more to someone with less money).

Chapter 26: Prospect Theory

- Kahneman and Tversky propose Prospect Theory as a better model of how people actually make decisions.

- Key principles:

- Loss aversion: Losses hurt more than gains feel good.

- Reference dependence: Outcomes are evaluated relative to a reference point, not in absolute terms.

- Diminishing sensitivity: Both gains and losses have decreasing marginal impact.

- This theory explains why people sometimes reject favorable bets or take irrational risks.

Chapter 27: The Endowment Effect

- People value something more once they own it, simply because they own it.

- This causes a gap between willingness to accept and willingness to pay.

- Related to loss aversion: giving something up feels like a loss.

Chapter 28: Bad Events

- Negative emotions and experiences are more powerful than positive ones.

- We react more strongly to threats and losses.

- This asymmetry shapes relationships, decision-making, and even legal systems.

Chapter 29: The Fourfold Pattern

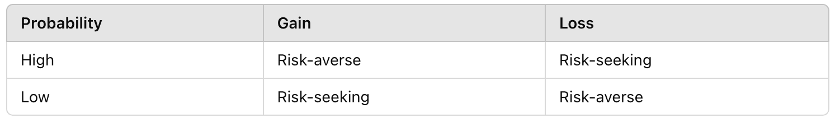

- People’s attitudes toward risk change depending on probability and whether the outcome is a gain or a loss:

- This explains behaviors like buying lottery tickets and insurance—both of which defy rational utility theory.

Chapter 30: Rare Events

- People overweight rare events when they are described but underweight them when they are experienced.

- This leads to paradoxes like overestimating the danger of terrorism but ignoring everyday risks like driving.

- Vividness and emotional charge of rare events magnify their perceived impact.

Chapter 31: Risk Policies

- Kahneman recommends broad framing: don’t treat every decision as a one-off.

- Develop risk policies (e.g., always accept a 50/50 bet with a good expected value).

- This helps override our instinctive aversion to short-term losses.

Chapter 32: Keeping Score

- People mentally track gains and losses, even if it’s irrational to do so.

- We’re especially reluctant to accept losses, even when they’re part of a longer-term win.

- Mental accounting causes people to treat money differently depending on context (e.g., refund vs. bonus).

Chapter 33: Reversals

- Preferences can reverse depending on how choices are framed.

- Two logically identical problems can yield opposite choices if phrased differently.

- This violates the principle of invariance in rational decision-making.

Chapter 34: Frames and Reality

- Framing effects show that the way information is presented changes our decisions.

- People often respond to the form of a problem, not just the content.

- This has major implications for marketing, policy, and ethics.

Key Takeaway from Part IV:

People don’t make decisions based on objective outcomes—they make them based on how choices are framed, their reference points, and their emotional response to gains and losses. We are not rational maximizers of utility; we are emotional, biased decision-makers trying to avoid regret and losses.

Part V: Two Selves

This final section explores the Experiencing Self (who lives through moments) and the Remembering Self (who tells the story of our life). Kahneman shows that we often make decisions for our remembering self, even if they come at the cost of present happiness.

Chapter 35: Two Selves

- We have two distinct perspectives on our lives:

- The Experiencing Self: lives moment to moment.

- The Remembering Self: reflects on experiences and makes choices.

- The two selves often disagree on what constitutes a good life or good decision.

- Example: A vacation with a terrible last day might be remembered negatively, even if most of it was enjoyable.

Chapter 36: Life as a Story

- The remembering self creates a narrative based on significant moments, especially the peak (best/worst part) and the end.

- This is known as the Peak-End Rule: we judge experiences based on how they felt at their peak and how they ended, not on duration.

- Duration neglect: the length of an experience barely affects how we remember it.

Chapter 37: Experienced Well-Being

- Experienced well-being is measured by how people feel in the moment, not what they remember.

- Kahneman uses time-use surveys to track actual enjoyment throughout the day.

- Activities like commuting are high in stress and low in happiness; socializing and relaxing bring more moment-to-moment joy.

- Money correlates with well-being only up to a point (about $75,000/year, at the time of the study); beyond that, it doesn’t increase happiness significantly.

Chapter 38: Thinking About Life

- When people evaluate their lives, they mostly consult the Remembering Self, not the Experiencing Self.

- This affects major decisions (career, marriage, children) that are often made for long-term narrative satisfaction rather than daily happiness.

- Kahneman suggests a tension between being happy in your life and being happy about your life.

- Final point: we should think carefully about which self we are trying to please—because they want different things.

Key Takeaway from Part V:

We are guided by two selves: the Experiencing Self, who lives in the present, and the Remembering Self, who makes decisions and tells the story. Many of our life choices are based on what we think we’ll remember fondly, not what actually feels good in the moment. This can lead us to sacrifice actual happiness for a better story.

5 thoughts on “Book Club: Rethinking How We Think – The Enduring Power of Thinking, Fast and Slow”