[Written by Grok]

Pre-19th Century: Ancient Ties and Coexistence

Long before recorded history, the land now called the United States was home to the Native Nations, a diverse tapestry of tribes—Cherokee, Sioux, Navajo, and hundreds more—whose cultures, languages, and spiritual traditions were rooted in the mountains, plains, and rivers. Their sacred stories spoke of a covenant with the Creator, granting them stewardship over the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific. By the 1500s, an estimated 10 million Native Americans thrived, living in harmony with the earth.

In the 16th century, newcomers—Settlers from Europe—arrived, driven by dreams of wealth, religious freedom, and empire. They claimed the land under doctrines like Manifest Destiny, believing it their divine right to “civilize” the wilderness. Over centuries, the Settlers displaced the Native Nations through wars, disease, and broken treaties (e.g., the 1830 Indian Removal Act, akin to early Ottoman land policies in Palestine). By the 1800s, Native populations dwindled to 250,000, confined to barren reservations, while Settlers built a burgeoning nation, the United States, across 98% of the land.

Late 19th Century: The Native Revival Movement

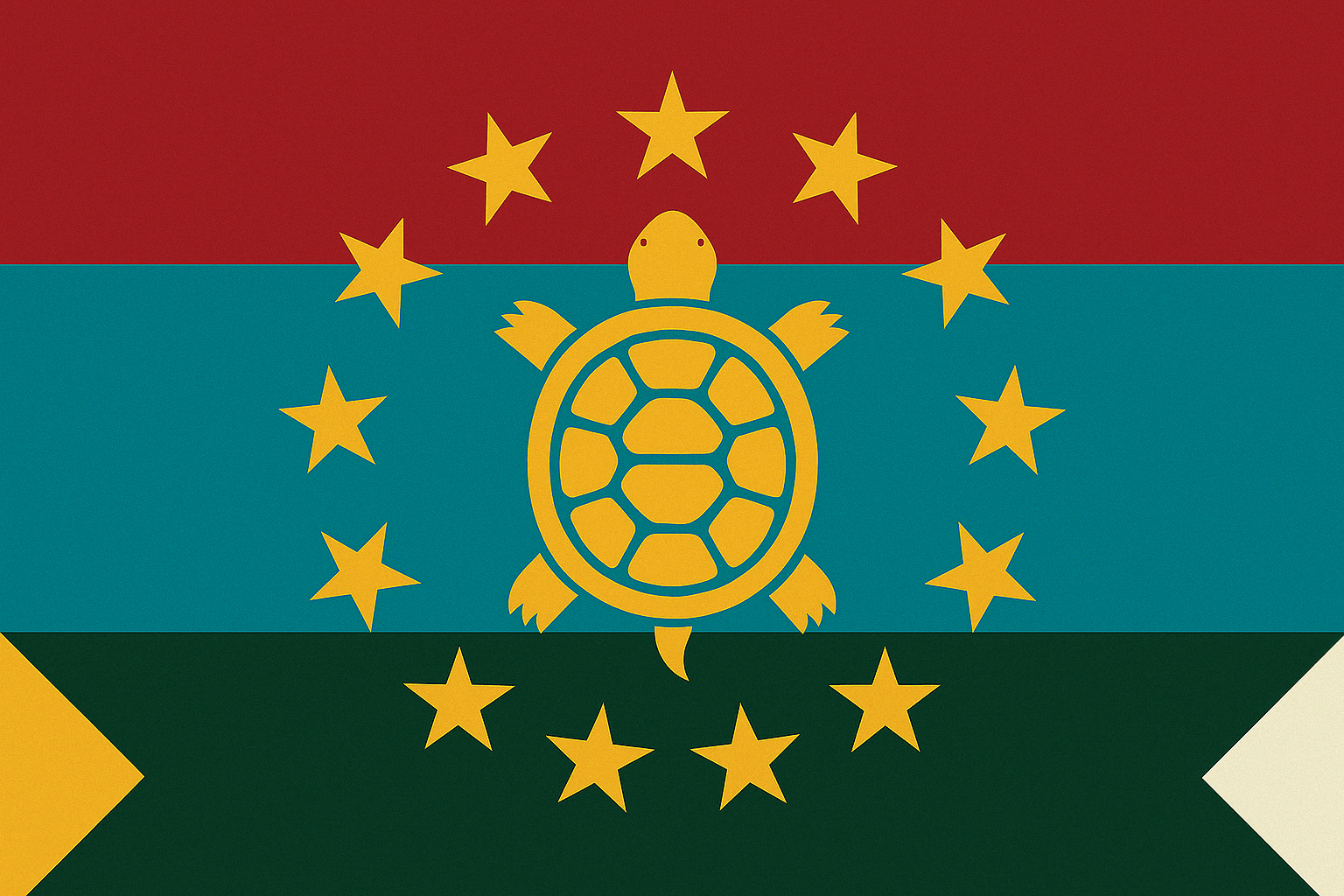

By the 1880s, Native Americans, scattered across reservations and diaspora communities (akin to Jewish exile), faced cultural erasure. A new movement, “Natavism,” emerged, inspired by figures like Wovoka, who preached a spiritual and political return to ancestral lands. Natavists argued the Creator’s covenant and their millennia-long presence justified reclaiming the United States as a Native homeland, not just for religious reasons but to escape persecution and restore dignity after genocide (paralleling Zionism’s response to antisemitism).

Unlike historical Native resistance (e.g., Sioux Wars), Natavism gained global sympathy. European powers, guilty over colonial atrocities, and a nascent League of Nations endorsed a Native homeland. Settlers, now 50 million strong, saw the land as their birthright, built on centuries of toil, and viewed Natavist claims with suspicion, fearing loss of their homes (mirroring Palestinian reactions to early Zionism).

Early 20th Century: Migration and Tensions

From the 1890s to 1930s, Native Americans from reservations and abroad (e.g., urban diaspora, akin to Jewish immigration) began returning to key regions—Oklahoma, the Dakotas, and Arizona—buying land or settling in underpopulated areas. Supported by international funds (like the Jewish Agency), they established self-governing communities, reviving languages and traditions. By 1940, 500,000 Natives lived in these enclaves, a small but growing presence.

Settlers, whose towns and farms dominated the landscape, grew alarmed. Clashes erupted, like the fictional “Tulsa Riots” of 1921, where Settler militias attacked Native settlements, and Native defenders retaliated (akin to 1929 Hebron riots). Both sides formed militias: Native “Red Hawks” (like Haganah) and Settler “Patriot Guards” (like Arab irregulars). The U.S. government, under British-like federal oversight, struggled to mediate, promising both groups rights but fueling mistrust.

1947–1948: Partition and War

In 1947, a global body, the United Nations, proposed a partition plan to resolve the growing conflict. The United States would be split: 55% for a Native state (including Oklahoma, parts of the Dakotas, and Arizona, areas of historical significance) and 45% for a Settler state, with shared control over sacred sites like the Black Hills (akin to Jerusalem). The Native Nations, desperate for sovereignty after centuries of loss, accepted. Settlers, who owned most land and saw partition as unjust, rejected it, fearing fragmentation of their nation (paralleling the 1947 UN Partition Plan).

In 1948, the Native Nations declared independence, establishing the Native States of America (NSA), with a capital in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. War broke out as Settler militias and neighboring states (e.g., Canada, Mexico, in place of Arab states) attacked to prevent NSA’s formation. The Native forces, armed with international support and guerrilla tactics, prevailed, capturing 75% of the U.S., including key cities like Tulsa and Rapid City. During the war, 700,000 Settlers fled or were expelled—some due to Native attacks (e.g., a fictional “Sioux City Massacre”), others fearing violence or following militia orders (mirroring the Nakba). They became refugees in urban enclaves like Chicago’s “Settler Strip” or rural “West Counties” (akin to Gaza and West Bank).

1948–1967: Consolidation and Division

The NSA, now home to 1 million Natives (including diaspora returnees), built a democratic state, reviving tribal governance and culture. It prevented Settler refugees from returning, citing security risks, and absorbed 500,000 Native immigrants (paralleling Israel’s post-1948 policies). The Settler Strip, under a neighboring state’s control (e.g., Canada, like Egypt’s Gaza), and West Counties, annexed by another (e.g., Mexico, like Jordan’s West Bank), housed 2 million displaced Settlers in crowded camps, with limited rights (akin to Palestinian refugees).

Tensions simmered. Settler resistance groups, like the “Patriot Dawn” (like PLO), launched raids, killing Native civilians. The NSA responded with border fortifications and airstrikes, deepening Settler grievances. By 1967, a second war erupted when neighboring states mobilized against the NSA. The NSA preemptively struck, capturing the Settler Strip and West Counties in six days, placing 1.5 million Settlers under military occupation (mirroring the 1967 Six-Day War).

1967–Present: Occupation and Conflict

The NSA’s occupation transformed the conflict. In the West Counties, Native settlements expanded, with 500,000 Natives moving to ancestral lands, often displacing Settler homes (like West Bank settlements). Checkpoints and a separation wall restricted Settler movement, citing attacks like the fictional “Oklahoma City Bombing” of 1975 (akin to Second Intifada). In the Settler Strip, a militant group, “Liberty Front” (like Hamas), took control in 2007, prompting an NSA blockade that crippled the economy, leaving 80% aid-dependent (like Gaza’s blockade).

Violence became cyclical (“violence begets violence”). Settler rocket attacks and suicide bombings killed 1,000 Natives since 2000, while NSA operations killed 30,000 Settlers, mostly civilians, in retaliatory strikes (paralleling Gaza wars). A 2023 “Liberty Front” attack killed 1,200 Natives, triggering a massive NSA campaign that devastated the Settler Strip, displacing 1 million (like October 2023 Hamas attack and aftermath).

Peace Efforts and Stalemate

Peace talks, like the fictional “Denver Accords” of 1993 (like Oslo), aimed for a two-state solution: NSA alongside a Settler state in the Strip and Counties. Initial progress—e.g., limited Settler autonomy—faltered as Native settlements grew and Settler militancy persisted. By 2025, only 25% of Natives support two states (down from 50% in 1990s), fearing loss of ancestral lands, while 60% of Settlers back armed resistance, per polls (mirroring Israel Democracy Institute and PCPSR data).

The NSA pursues a security-first approach, building advanced defenses and controlling Settler enclaves, believing peace requires Settler disarmament. Progressive Natives, like the “Harmony Council” (like B’Tselem), call for ending occupation, citing Settler poverty (40% unemployment in Strip) as inhumane, but they’re marginalized (10% support). Settlers demand right of return to lost lands, like Tulsa, which the NSA rejects, fearing demographic shifts (like Palestinian right of return).

University Debates and External Pressures

At elite U.S. universities (e.g., Harvard, Columbia), the conflict sparks heated debates. Settler advocates, like “Freedom for Settlers” (like SJP), protest NSA policies, calling settlements theft and blockades inhumane. Native defenders, like “Native Unity” (like StandWithUs), argue security justifies measures, citing Liberty Front attacks. Rhetoric escalates—e.g., “Natavism is colonialism” draws accusations of anti-Native bias (akin to antisemitism claims). A federal leader, echoing Trump’s policies, threatens university funding unless “anti-Native hate” is curbed, chilling Settler activism (like Title VI probes).

Current State

In 2025, the Native States of America thrives, with 5 million Natives, but faces global criticism for occupation. The 4 million Settlers in the Strip and Counties live under restrictions, with limited prospects, fueling resistance. Both sides see themselves as victims: Natives fear losing their hard-won homeland, Settlers mourn their displaced ancestors. The cycle of violence persists, with no clear path to peace, as mutual distrust overshadows fleeting hopes for coexistence.

2025–2100: Escalation and Stagnation

Over the 21st century, the Native-Settler conflict intensified, driven by resource scarcity and technological disparities. Climate change ravaged the Settler Strip, where rising temperatures and flooding displaced 500,000 into denser camps (akin to Gaza’s environmental woes). The NSA, leveraging advanced terraforming, made its lands resilient, widening the economic gap (NSA GDP per capita $80,000 vs. Strip’s $2,000, per fictional 2080 data). Settler resistance evolved: the Liberty Front deployed AI-guided drones, killing 2,000 Natives in a 2075 attack, prompting NSA orbital strikes that leveled Settler infrastructure, killing 50,000 (paralleling Gaza wars).

Peace efforts faltered. A 2050 “Global Accord” proposed a confederated state with shared governance, but Native fears of demographic shifts (Settlers projected to outnumber Natives by 2100) and Settler demands for full land return (akin to Palestinian right of return) derailed it. NSA settlements grew to 1 million, fragmenting West Counties further (like West Bank settlements, 700,000 in 2024). Universities, now virtual hubs, saw Settler activism branded as “digital terrorism,” with AI censors enforcing anti-Native bias laws (extending Trump-like policies).

2100–2300: Technological Divergence and Stalemate

By the 22nd century, technology reshaped the conflict. The NSA developed quantum shields, neutralizing Settler attacks, while Settlers in the Strip used bioengineered viruses, sparking a 2150 pandemic that killed 100,000 across both groups (mirroring bioterrorism fears). The West Counties became a surveillance state, with NSA neural implants tracking Settler movements, reducing violence but deepening resentment (like Israel’s checkpoint tech). Off-world colonies, led by global powers, offered emigration, but only 200,000 Natives and 300,000 Settlers left, as most clung to ancestral claims (unlike Palestinian diaspora growth).

A 2200 “Lunar Summit,” mediated by a post-UN Galactic Council, proposed a one-state solution with equal rights. Native leaders, now 40% of a 10 million population (Settlers at 60%), rejected it, fearing cultural erasure, while Settler radicals, citing 1948’s “Great Exile,” demanded NSA dissolution. Violence subsided due to tech disparities—NSA’s autonomous drones quelled uprisings—but Settler poverty (50% unemployment) and Native paranoia persisted. Global universities, on orbital campuses, debated the conflict, with Settler narratives flagged as “heritage denial,” echoing 2025’s anti-Native bias accusations.

2300–2450: Climate Crisis and Coexistence Experiments

The 24th century brought a climate tipping point. Mega-droughts rendered the Settler Strip nearly uninhabitable, forcing 2 million into West Counties or NSA-controlled zones as “climate refugees” (akin to Gaza’s 1.9 million displaced, 2024). The NSA, facing global sanctions for water hoarding, experimented with coexistence: “Harmony Zones” in Oklahoma integrated 500,000 Settlers with Natives under joint governance (like Israeli-Palestinian grassroots projects). These zones, using AI-mediated councils, reduced violence, with only 100 deaths annually vs. 10,000 in 2100.

However, hardliners resisted. Native purists, citing sacred covenants (like religious Zionism), expanded settlements to 2 million, while Settler “Returnists” launched cyberattacks, disrupting NSA power grids. A 2400 treaty, the “Great Plains Accord,” proposed a federated state with autonomous Native and Settler regions, but only 30% of Natives and 35% of Settlers supported it (mirroring 2024 polls: 28% Israeli, 35% Palestinian for two states). Universities, now neural networks, saw Settler historians penalized for “revisionist” claims about 1948, perpetuating 2025’s censorship trends.

2450–2525: Toward Fragile Integration

By 2525, the Native-Settler conflict has transformed, though not fully resolved. The NSA, with 15 million citizens (40% Native, 50% Settler, 10% mixed), governs a unified but tense state after a 2500 “Unity Pact.” The Pact, driven by mutual survival amid a post-climate Earth (30% land lost to seas), dissolved the Settler Strip and West Counties, granting Settlers citizenship but limiting their political power to prevent Native minority rule (akin to one-state scenarios). Settlements were frozen, with 3 million Natives relocated to urban cores, easing land disputes.

Violence is rare, thanks to neural pacification tech, but cultural tensions linger. Settler “Memory Festivals” commemorate 1948’s exile, provoking Native counter-rallies celebrating NSA’s founding (like Israel’s Independence Day vs. Nakba Day). Economic gaps persist: Native elites control 70% of wealth, while Settlers face 20% unemployment (down from 50%). Education systems, unified via AI curricula, teach dual narratives—Native revival and Settler loss—but debates flare in virtual forums, with “anti-Native” labels still weaponized (echoing 2025 university dynamics).

Globally, the NSA is a mid-tier power, overshadowed by off-world empires. Exo-universities study the conflict as a case of “terrestrial reconciliation,” but Settler descendants demand reparations for 1948, while Natives cite centuries of pre-1948 genocide as justification (paralleling Israeli-Palestinian historical grievances). A small “Harmony Movement,” blending Native spirituality and Settler resilience, gains traction, with 10% of youth identifying as “Native-Settler” hybrids, hinting at cultural fusion.

Future Prospects

In 2525, the Native-Settler saga remains unresolved but less violent. The Unity Pact holds, driven by necessity, not trust. However, climate refugees from sunken continents (1 billion globally) strain resources, risking new conflicts. If the Pact collapses, Native hardliners could reimpose segregation, while Settler radicals might revive Returnist militancy, restarting the cycle (“violence begets violence”). Alternatively, continued integration, fueled by intermarriage and shared tech, could erode old divisions, creating a hybrid nation by 2700—though scars of 1948 endure.