We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.

– Aristotle

[Written by ChatGPT]

What makes a life good?

It’s a question philosophers, poets, and ordinary people have asked for centuries. In today’s world of hyper-productivity and hustle culture, the answer often seems to orbit one word: work. But is paid work truly essential for a good life? Or is meaning found elsewhere — perhaps in stillness, relationships, creativity, or simply being alive?

To explore this, we turn to ikigai, a Japanese concept that offers a grounded, human-scale perspective on purpose — and then expand the view with similar ideas from other cultures.

Ikigai: A Reason to Get Up in the Morning

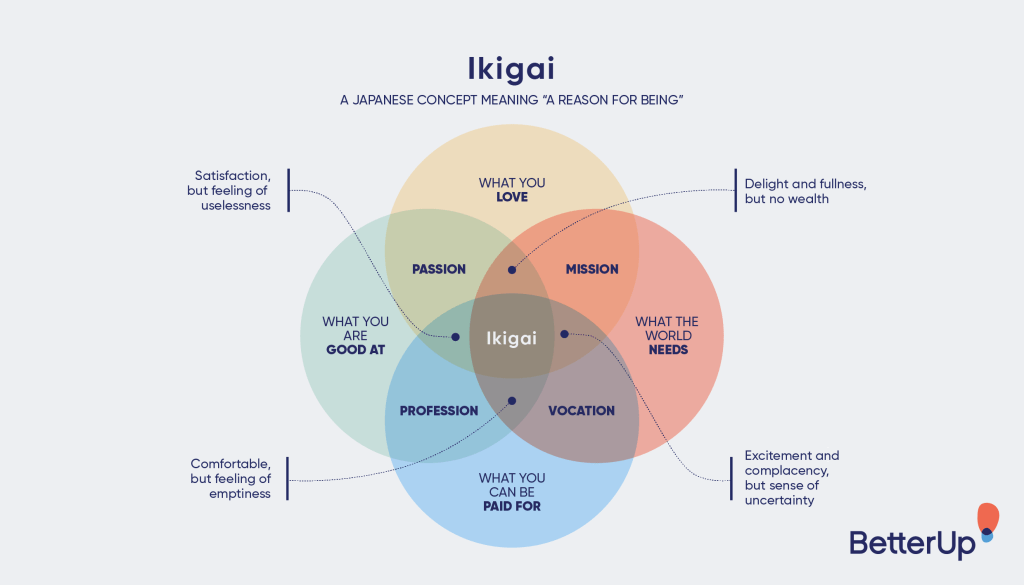

In Japan, ikigai (生き甲斐) means “a reason for being.” It’s what gives life flavor, direction, or a quiet sense of fulfillment. Western interpretations often reduce it to a tidy Venn diagram — the intersection of what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for.

But in its original cultural context, ikigai isn’t necessarily career-focused or tied to monetary gain. It can be:

- Drinking tea in the morning

- Caring for a grandchild

- Practicing a craft

- Watching the seasons change

Ikigai is less about achievement and more about continuity — the things that make you want to see tomorrow.

Across Cultures: Different Words, Same Heart

Other traditions echo this sense of grounded meaning:

- Dharma (India): A moral path or duty unique to each person, tied to both personal growth and social harmony.

- Ubuntu (Southern Africa): “I am because we are.” A philosophy of interconnectedness and purpose through community.

- Kuleana (Hawai’i): Responsibility with privilege — fulfilling your role in life with care and intention.

- Lagom (Sweden): Not too much, not too little. A balanced life — enough to feel secure, not so much that it overwhelms.

- Raison d’être (France): A more existential term — your reason for being.

These concepts suggest that a meaningful life doesn’t always require success or status. Instead, it emerges from connection, contribution, rhythm, and presence.

Is Paid Work Essential?

For many, paid work is a necessity — it provides food, shelter, stability. But even beyond survival, work can offer structure, identity, and purpose. That’s why even those who are financially secure — millionaires, retirees, or royalty — often keep working.

But here’s the twist: it’s rarely just about money. Many wealthy people continue working because:

- They seek challenge or growth

- They crave relevance or influence

- Their work aligns with their ikigai, their raison d’être, or their dharma

In this sense, monetary compensation is not the point — it’s a side effect. What matters is engagement. Humans are wired to create, serve, and strive — not endlessly, but meaningfully.

The Good Life Is Not a Formula

There’s no universal answer to what makes life good. But some patterns emerge:

- A sense of belonging

- Activities that feel worthwhile

- Moments of beauty and wonder

- The ability to give and receive

- Enough freedom to shape your days

Paid work can support these things — or it can obscure them. The key is to ask: Does this align with what I truly value? If the answer is yes, whether you’re earning or not, you’re likely living something close to a good life.

Final Thought: Maybe the Miracle Is Enough

Sometimes, meaning doesn’t need to be earned or justified. As Zen teachings remind us, “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” The miracle is simply being here — awake to the world, able to choose how we meet it.

Ikigai isn’t a destination — it’s a companion. And the good life? It might just be the one you’re already living, if you pause long enough to notice.

[Image source]

2 thoughts on “The Good Life: Ikigai and the Search for Meaning Across Cultures”