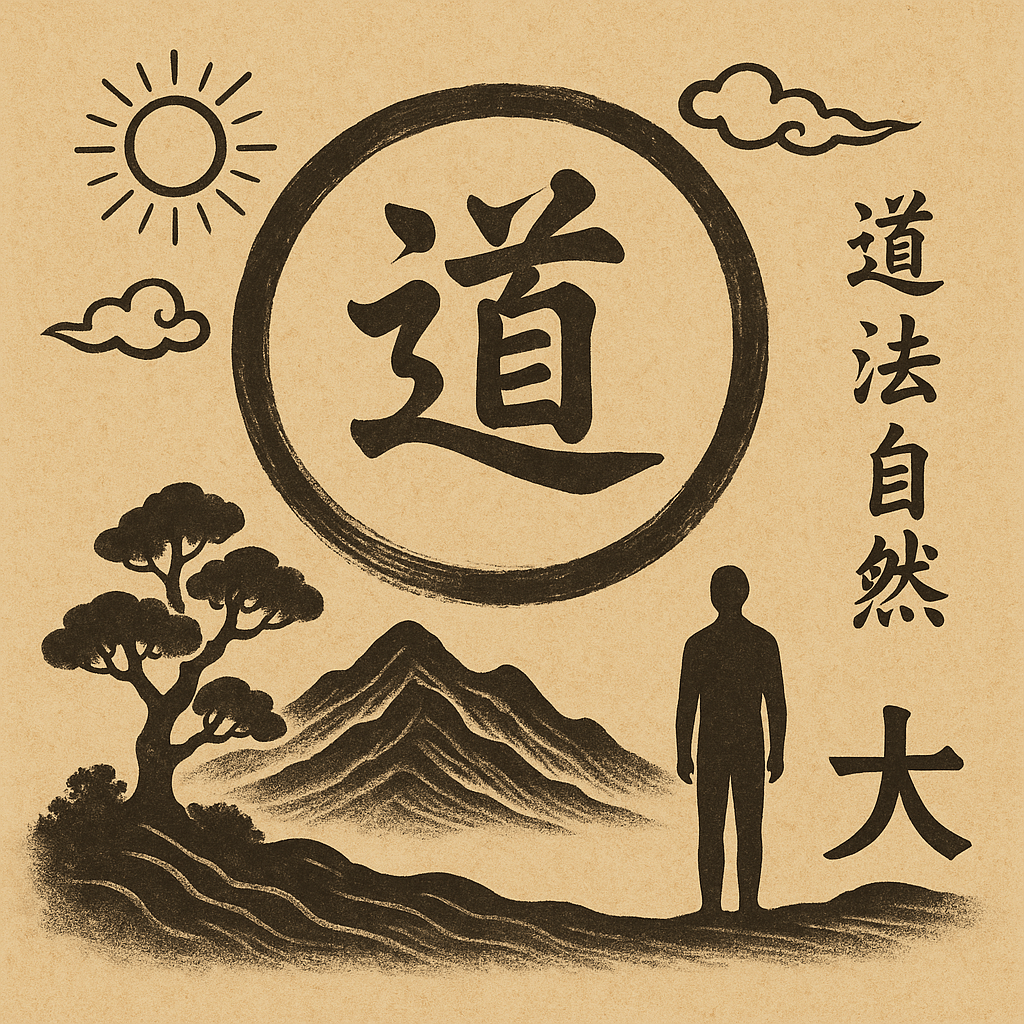

Verse 25 by Lao Zi: 有物混成,先天地生。寂兮寥兮,独立而不改,周行而不殆,可以为天地母。吾不知其名,强字之曰:道,强为之名曰:大。大曰逝,逝曰远,远曰反。故道大,天大,地大,人亦大。域中有四大,而人居其一焉。人法地,地法天,天法道,道法自然。

There is something formed from chaos,

Born before Heaven and Earth.

Silent and boundless,

Alone and unchanging,

It moves in cycles without exhaustion,

And can be called the Mother of Heaven and Earth.

I do not know its name;

I force myself to call it “Dao.”

If compelled to give it a designation, I call it “Great.”

Great means to flow on,

To flow on means to go far,

To go far means to return.

Therefore, Dao is great,

Heaven is great,

Earth is great,

And humanity is also great.

Within the universe, there are four greats,

And humanity dwells among them.

Humanity follows the Earth,

The Earth follows Heaven,

Heaven follows the Dao,

The Dao follows what is natural.

[Written by ChatGPT]

When we read ancient texts, we often expect to see humanity portrayed as either the pinnacle of creation or as tiny and insignificant compared to the cosmos. But in Chapter 25 of the Dao De Jing, Laozi does something different: he names four “greats” — Dao, Heaven, Earth, and Humanity.

This is a striking balance. Dao, the mysterious source of all things, comes first. Heaven, with its vast cycles of time and space, follows. Earth, the fertile ground that sustains life, is next. And then, alongside them, humanity is placed as the fourth great. Laozi doesn’t make us rulers of the universe, nor does he diminish us as powerless specks. Instead, he situates us as co-participants in the grand order.

Why call humans “great”? Unlike Earth and Heaven, which follow their courses automatically, humans have a special capacity: awareness. We can choose whether to live in alignment with the Dao or to resist it. In Daoist thought, this ability to consciously harmonize with nature is what makes us significant. Our greatness isn’t about domination — it’s about our potential to live wisely.

But Laozi also reminds us of humility. We are one among four, not the only “great.” Humanity follows Earth, Earth follows Heaven, Heaven follows Dao, and Dao follows what is natural. This chain of harmony places us within a larger system. Forgetting this — as when societies try to exploit the Earth without limit — throws everything out of balance. Remembering it brings us back into flow.

Seen this way, Laozi’s vision is both timeless and timely. To be “great” as humans is not to stand apart from nature but to belong within it. It is to recognize that our dignity comes from relationship, not dominance. In a world wrestling with environmental crises and social disconnection, this Daoist reminder feels as urgent as ever: humanity is truly great when it remembers its place among the Four Greats.

The Two Faces of Chapter 25: King or Human?

【第二十五章】有物混成,先天地生。寂兮寥兮,独立不改,周行而不殆,可以为天下母。吾不知其名,字之曰道,强为之名曰大。大曰逝,逝曰远,远曰反。故道大,天大,地大,王亦大。域中有四大,而王居其一焉。人法地,地法天,天法道,道法自然。

One of the most intriguing details in the Dao De Jing is how small variations in wording can reveal great shifts in meaning. Chapter 25, one of Laozi’s most majestic and mysterious verses, exists in slightly different forms across the centuries. Most modern readers encounter the line:

故道大,天大,地大,王亦大。域中有四大,而王居其一焉。

“Therefore Dao is great, Heaven is great, Earth is great, and the King is also great. Within the realm there are four greats, and the King is one among them.”

But in some later manuscripts, we find instead:

故道大,天大,地大,人亦大。域中有四大,而人居其一焉。

“Therefore Dao is great, Heaven is great, Earth is great, and Humanity is also great. Within the realm there are four greats, and Humanity is one among them.”

At first glance the difference seems small — one word replaced by another. Yet it changes the entire philosophical landscape.

From Cosmic Kingship to Human Participation

The earliest known manuscripts — the Guodian bamboo slips (c. 4th century BCE) and the Mawangdui silk texts (c. 2nd century BCE) — both use “王亦大”, “the King is also great.” This version reflects early Daoism’s deep connection with the art of rulership. The Dao, Heaven, and Earth form the great pattern of the cosmos, and the ideal ruler is “great” only by aligning with this order. Laozi’s teaching was not merely political, however; his king was meant to be a sage — a person who rules through non-action (wu wei) and harmony rather than coercion.

Centuries later, during the Han dynasty, commentators such as Heshang Gong began to reinterpret Laozi’s text in a more moral and personal way. In this spirit, the word “王 (king)” was replaced by “人 (human).” Now, greatness was not the privilege of rulers but the potential of every person who lived in accordance with Dao. The change reflects a shift from cosmic–political Daoism to existential–spiritual Daoism, emphasizing inner cultivation over imperial alignment.

“天下母” or “天地母”: The Universal Source

Another variation appears in the line “可以为天下母” — “it may be called the Mother of the world.” Some later texts change it to “可以为天地母,” “the Mother of Heaven and Earth.” The original “天下” (all under Heaven) implies the totality of existence, while the later version narrows it slightly to the cosmic duality of Heaven and Earth. The change again shows how scribes and commentators shaped Laozi’s poetry to reflect evolving cosmologies — from a vision of Dao as the source of everything to one as the harmonizer of the cosmic pair.

Layers of Meaning, One Endless Way

Both versions are meaningful. The older, canonical text of Wang Bi (3rd century CE) preserves the ancient sense of cosmic rulership — Dao as the pattern by which the sage-king governs the world. The later Heshang Gong and Daozang traditions universalize that message, turning it inward toward the heart of every person.

Whether the “four greats” include the king or all humanity, the insight is the same: true greatness arises only from harmony with Dao. The change of one character — 王 to 人 — beautifully mirrors Laozi’s own teaching that names and distinctions are secondary. The Way remains inexhaustible, quietly flowing beneath all interpretations.

The Three Faces of Dao: From Mystery to Cosmos

Reading the Dao De Jing feels like walking through mist that slowly reveals a mountain—each shape emerging, dissolving, and returning to silence. Among its 81 verses, three seem to form a hidden current: Verse 1, Verse 4, and Verse 25. Read together, they trace a movement from mystery, to presence, to order—the unfolding of Dao itself.

Verse 1 · The Unspeakable Beginning

“The Dao that can be spoken is not the constant Dao;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth;

The named is the mother of the ten thousand things.”

Laozi opens with a paradox. To name is to limit, and yet we cannot help but name. What he calls Dao points to the source prior to language and form—the pure “is-ness” of reality before thought divides it into this and that. He invites us not to analyze but to un-see: to perceive the world before labels harden around it.

This verse plants the seed of humility. If we are to sense Dao, we must first admit that our words and categories—though useful—cannot contain the real.

Verse 4 · The Living Emptiness

“The Dao is empty, yet its use is inexhaustible.

Deep—it seems the ancestor of all things.”

Having turned from words to wonder, Laozi now feels the Dao. It is emptiness that never runs dry, like a well that nourishes without depletion. The image of water—soft, silent, and yielding—returns again and again in his writing.

Here Dao is not absence but fertile openness: it softens what is sharp, dissolves confusion, and quietly harmonizes what exists. Verse 4 transforms the abstract mystery of Verse 1 into living experience. The reader is no longer thinking about Dao but standing inside its flow.

Verse 25 · The Great Pattern and the Act of Naming

“There is something formed from chaos,

Born before Heaven and Earth.

Silent and vast, standing alone and unchanging,

Circulating and never exhausted—

It may be called the Mother of the world.

I do not know its name; I call it Dao.

Forced to give it a name, I call it Great.”

In this verse, Laozi’s insight expands to cosmic scale. The nameless origin of Verse 1 and the inexhaustible source of Verse 4 now appear as the pattern of the universe itself—the rhythm by which Heaven, Earth, and life renew themselves.

Here Laozi also does something extraordinary: he explains why he names the unnameable. Standing before the mystery, he admits: “I do not know its name.” Yet to guide others, he chooses a word—Dao, meaning “way,” “path,” or “flow.” It is not a noun but a verb, a movement. In naming it, he emphasizes that reality is not static being but ongoing becoming.

Still feeling language’s limits, he adds another word—“Great” (大)—and unfolds its meaning: “Great flows forth (逝), goes far (远), and returns (反).” In this poetic cycle, Laozi captures Dao’s ceaseless self-renewal. Naming thus becomes not an act of control but of reverent approximation—a way to point toward what forever exceeds words.

Coherence in the Flow

The three verses describe the same reality through three lenses:

- Verse 1 names the unnameable—mystery.

- Verse 4 feels its breath—presence.

- Verse 25 sees its cosmic dance—order.

Together they trace a movement from silence to manifestation and back again. Laozi does not build a theory; he composes a rhythm. The Dao that cannot be spoken nevertheless speaks through everything—through emptiness, through flow, through the great turning of Heaven and Earth.

To read these verses together is to watch the infinite inhale and exhale.

To live them is to sense that same breath moving quietly through oneself.

One thought on “Dao, Heaven, Earth, and Humanity”