[Written by ChatGPT. Image credit]

After decades of watching myself and the people around me — friends, partners, colleagues — I’ve started to see the invisible patterns that shape how we connect, argue, comfort, and drift apart. It’s taken me years to realize that human interaction isn’t random; it’s guided by deep emotional wiring that begins early and continues to shape us throughout life. Recently, I’ve been exploring attachment theory, and it’s been eye-opening to see how much it explains about the recurring themes in my own relationships.

If you’re curious, you can take a quick test at attachmentquiz.com to see your own attachment style — and even compare results with your partner. What fascinates me most is that attachment isn’t just about how we were raised; it’s also about how our brain is built and molded by experience. Our nervous systems literally learn what love and safety feel like — and they keep repeating those lessons until we consciously rewrite them.

Related post: The Four Attachment Styles

Introduction

Attachment theory, developed in the mid-20th century by John Bowlby, revolutionized the understanding of human emotional development. Bowlby proposed that attachment is an evolutionary system designed to ensure infant survival by keeping caregivers close. Later, Mary Ainsworth expanded on his ideas through empirical research, most notably the Strange Situation experiments. Her work identified three primary attachment styles in children: secure, anxious (ambivalent), and avoidant. These early relational patterns form internal “working models” — cognitive and emotional templates for how safety and closeness are experienced — and tend to persist into adulthood unless reshaped by new, consistent emotional experiences.

Secure and Insecure Attachment

In secure attachment, the caregiver is consistently responsive and comforting. The child learns that emotional expression and proximity lead to safety and soothing, forming a stable foundation for later autonomy and intimacy.

In insecure attachment, caregiving is inconsistent, intrusive, or emotionally unavailable. Children adapt to uncertainty in two broad ways:

- Anxious (ambivalent) attachment amplifies emotional signaling — clinging, crying, or hypervigilance — to gain attention.

- Avoidant attachment suppresses emotional expression and closeness, minimizing the pain of rejection.

Both insecure patterns are adaptive strategies for managing emotional needs in unpredictable environments but can become limiting in adult relationships.

Attachment Dynamics in Adulthood

Attachment patterns influence how adults form and sustain intimacy. Anxious–avoidant pairings are often the most turbulent: the anxious partner seeks reassurance and closeness, while the avoidant partner withdraws to protect their autonomy. This “pursue–withdraw” dynamic reinforces each person’s fears — abandonment for the anxious partner and engulfment for the avoidant.

In anxious–anxious relationships, both partners crave closeness but fear rejection, creating cycles of emotional intensity and dependency.

In avoidant–avoidant relationships, both partners suppress vulnerability; their bond may appear calm or functional but often lacks emotional depth and connection.

These dynamics illustrate that adult attachment behavior is the continuation of early neural and emotional patterns seeking security and regulation.

The Biological Basis of Attachment

The Limbic System

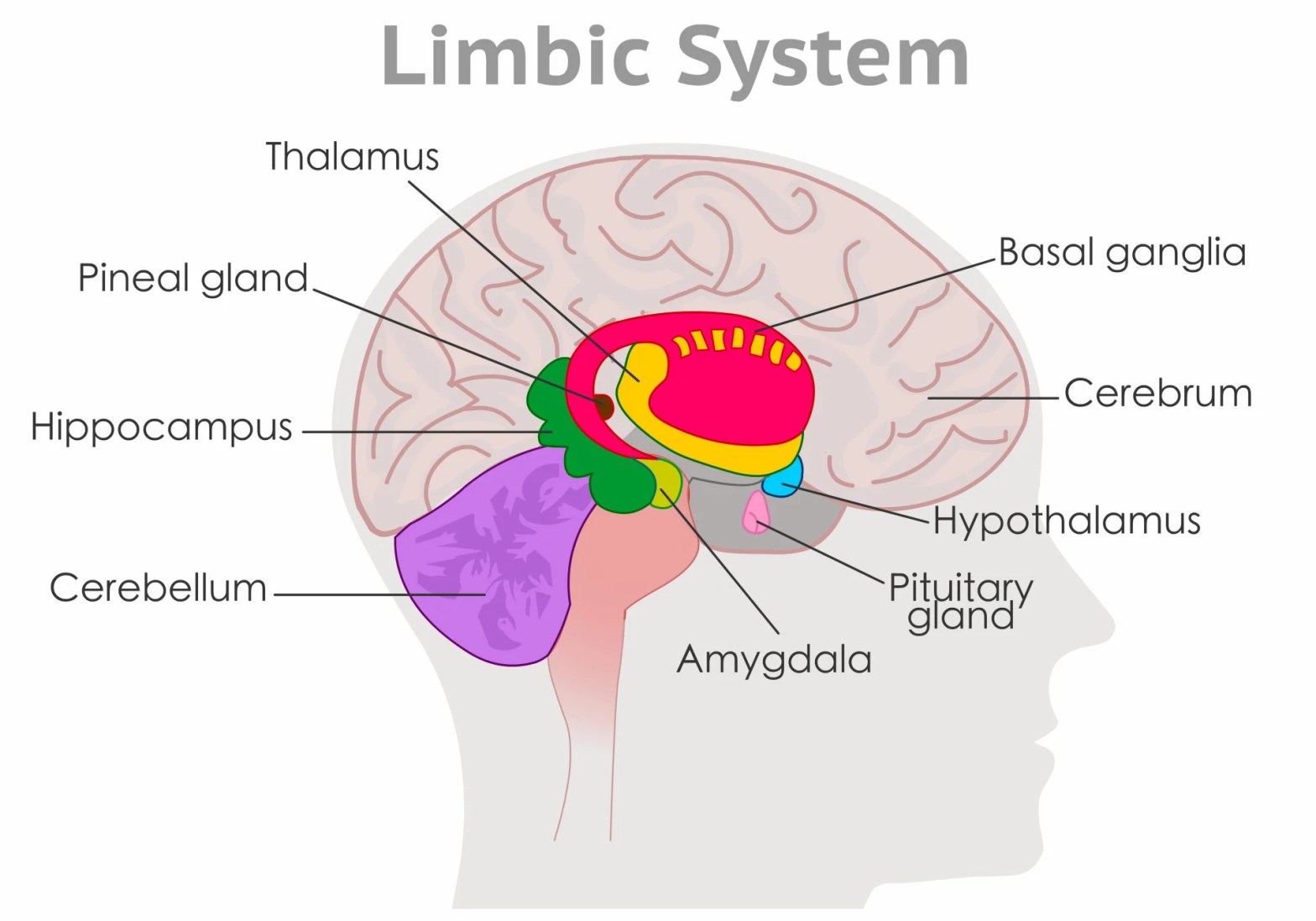

Attachment is not only psychological but deeply biological. It is rooted in the limbic system — the brain’s emotional center — and involves several key structures:

- Amygdala: Detects threat and regulates fear; overactivation is linked to anxiety and insecure attachment.

- Hippocampus: Encodes emotional memories and contextualizes attachment experiences.

- Hypothalamus: Releases bonding hormones like oxytocin and vasopressin and regulates stress via the HPA axis (cortisol).

- Cingulate cortex: Integrates emotional pain, empathy, and social rejection.

- Nucleus accumbens: Connects limbic emotion with reward, processing the pleasure of closeness.

Thus, the limbic system is the biological seat of attachment, responsible for generating and maintaining emotional bonds.

Beyond the Limbic System

Attachment also engages regions that regulate and interpret limbic signals:

- Prefrontal cortex: Especially the medial and orbitofrontal areas, which provide top-down regulation of emotional responses, empathy, and self-soothing.

- Insula: Integrates internal body sensations with emotion (“gut feelings”).

- Brainstem and autonomic circuits: Control heart rate, respiration, and physiological arousal during attachment and separation.

In secure attachment, these brain areas work in synchrony — sensory input leads to limbic activation, cortical interpretation, bodily feedback, and emotional balance. In insecure attachment, limbic overactivation or cortical suppression leads to dysregulation.

Neurochemistry of Attachment

Attachment is mediated by several neurotransmitters and hormones:

- Oxytocin: Promotes bonding, trust, and empathy; released during touch, eye contact, and caregiving.

- Vasopressin: Facilitates pair bonding and protective attachment.

- Dopamine: Reinforces the reward of closeness and social interaction.

- Endorphins: Create warmth and comfort in emotional connection.

- Cortisol: The stress hormone; elevated during separation and reduced through secure attachment.

A secure attachment profile reflects high oxytocin and dopamine with stable, low cortisol. Insecure attachment, by contrast, is characterized by low oxytocin, high cortisol, and overactive limbic circuits.

Attachment Styles as Nervous System Patterns

Attachment styles are embodied neural and hormonal configurations that shape how a person reacts to intimacy and stress.

| Attachment Style | Core Regulation Pattern | Nervous System Mode |

| Secure | Balanced activation: can seek closeness and self-soothe | Sympathetic–parasympathetic balance |

| Anxious (preoccupied) | Overactivation: seeks closeness to reduce fear | Sympathetic dominance (fight/flight) |

| Avoidant (dismissive) | Underactivation: suppresses emotion and proximity needs | Parasympathetic “shutdown” (freeze/numb) |

Anxious Attachment

- Amygdala: Hyperactive; constant vigilance for rejection or loss.

- Hypothalamus: Overactive HPA axis; elevated cortisol.

- Oxytocin: Released but ineffective due to inconsistent regulation.

- Prefrontal cortex: Weak inhibition of limbic surges → difficulty self-soothing.

Summary: The brain learns that connection is uncertain, producing clinging behavior and emotional reactivity.

Avoidant Attachment

- Amygdala: Underactive or inhibited; muted fear and emotion.

- Hypothalamus and brainstem: Reduced oxytocin and vagal tone; closeness feels unrewarding.

- Prefrontal cortex: Over-regulation suppresses emotional awareness.

- Insula: Diminished interoception and empathy.

Summary: The brain learns that closeness leads to disappointment; it dampens emotional circuits to avoid vulnerability.

Autonomic and Hormonal Correlates

| System | Anxious Attachment | Avoidant Attachment |

| Sympathetic Activation | High (“hyperarousal”) | Low (“emotional flatness”) |

| Parasympathetic Tone | Weak or inconsistent | Overcontrolled, numbed |

| Cortisol | Elevated baseline, prolonged stress | Blunted or delayed response |

| Body Posture | Leaning in, tense | Rigid, withdrawn |

Both patterns are learned survival strategies — the anxious body “reaches forward,” while the avoidant body “pulls back.”

Cortical Integration and Regulation

Secure attachment depends on a well-developed prefrontal–limbic loop:

- Calms the amygdala during distress

- Enables empathy via mirror neuron systems

- Maintains emotional stability and perspective

Anxious individuals have weak cortical regulation (limbic flooding), while avoidant individuals show excess regulation (emotional suppression). Thus:

- Anxious = too much limbic activation, weak brakes

- Avoidant = strong brakes, muted emotion

Conclusion: The Embodied Dance of Attachment

Both anxious and avoidant attachment styles represent adaptive neural strategies to early caregiving environments.

- The anxious style amplifies emotional signals to gain attention from inconsistent caregivers.

- The avoidant style dampens emotional signals to avoid pain from rejection.

Over time, these become embodied patterns — stable configurations of brain chemistry, nervous system tone, and body posture. Adult intimacy reactivates these patterns until new, consistent experiences of safety and trust help rewire them toward earned secure attachment.

Attachment theory, therefore, bridges psychology and biology: it reveals how the limbic system feels, the prefrontal cortex understands, and the body remembers. It is both a science of love and a neuroscience of regulation — explaining how the human need for connection is literally wired into the brain.