[Written by Claude]

For years, I carried around a simple mental image of the brain: a tangled web of neurons firing electrical signals back and forth. It seemed elegant, even poetic—billions of these specialized cells communicating in an intricate dance that somehow produced thoughts, memories, and consciousness itself. But the more I learned about neuroscience, the more I realized how incomplete this picture was.

The truth is, the brain is far more complex and fascinating than just a neural network. Yes, neurons are the stars of the show—the approximately 86 billion cells that transmit electrical and chemical signals throughout our nervous system. But they’re supported by an equally impressive cast of characters that I’d never really considered.

Take glial cells, for instance. These cells actually outnumber neurons in our brains, yet they rarely get the credit they deserve. Far from being mere “glue” (which is what “glia” means in Greek), these cells provide structural support, deliver nutrients, remove waste, and even help regulate the speed and efficiency of neural signals. What’s particularly interesting is that the ratio of neurons to glial cells varies dramatically across different brain regions—the cerebral cortex has roughly equal numbers of each, while the cerebellum is packed much more densely with neurons. Each region seems to have evolved the precise balance it needs for its specific functions.

This brings us to the brain’s distinctive anatomy: grey matter and white matter. Grey matter is where the action happens—it’s packed with neuron cell bodies, dendrites, and unmyelinated axons, making it the brain’s primary processing center. Its greyish hue comes from the dense concentration of cell bodies and blood vessels. White matter, on the other hand, is made up largely of myelinated axons—long nerve fibers wrapped in a fatty insulation called myelin. These are the brain’s communication cables, and the myelin gives them their pale, whitish appearance while dramatically speeding up signal transmission between different brain regions.

Understanding this complexity has completely transformed how I think about the brain. It’s not just a computer made of neurons—it’s an ecosystem.

The Human Brain: Anatomy, Cells, Composition & Comparison

[Written by ChatGPT. Checked by Grok and regenerated. Then checked by ChatGPT again for final output.]

The adult human brain weighs about 1.3 kg (typical range ~1.1–1.5 kg). Large post-mortem series consistently show higher mean values in males than females (≈ 1330 g vs ≈ 1200 g), with age-related decline later in life. (SciELO)

Below is a clear, sourced breakdown of what the brain is made of, how cells and materials differ by region, how connected those regions are, and how humans compare across species. Where precise measurements don’t yet exist (e.g., mass per cell class), you’ll see labeled estimates plus what research could resolve next.

1) Cells: how many, and where?

Best-supported totals (adult human):

- Neurons: ~86 ± 8 billion

- Non-neuronal cells (mostly glia + vascular): ~84.6 ± 9.8 billion

- Overall ≈ 1:1 neuron : non-neuron ratio (debunks the old “10× glia” myth). (PubMed)

By major region (neurons):

- Cerebral cortex (neocortical gray): ~16 billion

- Cerebellum: ~69 billion

- Rest of brain (brainstem + diencephalon + basal ganglia; “RoB”): < 2 billion

Together, the cerebral cortex + its white matter comprise ~82% of total brain mass, yet hold ~19% of neurons; the cerebellum holds ~80% of neurons in ~10% of the mass. (Fré.UY)

Glia:neuron ratios (regional):

- Cerebral cortical gray: ~1.5:1 non-neuronal : neuronal

- Cerebellum: ~0.23:1 (neurons dominate)

- RoB: ~11:1 (note: possibly inflated because some brainstem neurons are NeuN-negative and undercounted by the method). (Fré.UY)

2) What are those cells made of? (Material composition)

On a wet-weight basis, human brain tissue is roughly water-rich with sizeable lipid and protein fractions; white matter is more lipid-dense than gray matter because of myelin.

- Gray matter water content (in vivo): ~0.83 g/mL

- White matter water content (in vivo): ~0.71 g/mL

(White matter has more myelin; gray matter has more water.) (PubMed) - Myelin composition (dry mass): ~70–85% lipid, ~15–30% protein. (PMC)

- Classic biochemistry: white matter dry-weight lipids ~49–66% vs gray matter ~36–40%; region-specific lipid classes vary. (PubMed)

Region-by-region (human, typical adult)

| Region | Mass share | Neurons (approx.) | Glia:Neuron (non-neuron:neuron) | Water (in vivo) | Lipid (dry-mass tendency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral cortical gray | part of the ~82% cerebrum | ~16 B | ~1.5:1 | ~0.83 g/mL | ~36–40% (dry) |

| Cerebral white matter | part of the ~82% cerebrum | < 1 B (mostly axons) | high (myelin-rich) | ~0.71 g/mL | higher than gray; myelin ≈ 70–85% lipid (dry) |

| Cerebellum | ~10% of mass | ~69 B | ~0.23:1 | (mixed; white > gray) | myelin-rich white matter |

| RoB (brainstem + diencephalon + BG) | remainder | < 2 B | ~11:1 (method caveat) | mixed | mixed |

(Gray/white water values from quantitative MRI; lipid tendencies from classic lipid chemistry and myelin reviews.) (PubMed)

3) How connected are these regions?

Orders of magnitude (what’s well-grounded):

- Neocortex: each pyramidal neuron typically receives tens of thousands of synapses; total neocortical synapses are often inferred around ~10¹⁴ (order-of-magnitude). (OUP Academic)

- Cerebellum: despite tiny granule cells, the circuit explodes combinatorially. One review estimates parallel-fiber → Purkinje synapses at ~10¹⁴ in humans (≈ 100,000 billion), highlighting massive divergence and convergence at this single connection class. (PubMed)

Clarification: A granule cell receives ~4–5 mossy-fiber inputs (its “claws”) but makes many dozens to hundreds of outputs via its parallel fiber, leading to vast total synapse numbers even though each granule cell is small. (PMC)

Because many regional synapse inventories remain incomplete or species-specific, it’s safer to communicate orders of magnitude (10¹³–10¹⁴+ per major system) than fixed percentages of “the whole brain’s connections.”

4) Do we know how much neurons vs glia weigh?

Not precisely. We have excellent counts, but no consensus gram-level split of total mass into “neurons vs glia vs myelin vs vasculature” by region. Reasons: neurons and glia are interwoven; oligodendrocytes contribute disproportionately via myelin; regional water and lipid fractions vary; and counting methods (e.g., isotropic fractionator) deliberately discard morphology to get accurate counts. (PubMed)

Labeled estimate (use with caution)

- In white-matter-rich tissue, because myelin dry mass is ~70–85% lipid, the non-neuronal compartment (glia + myelin + vessels) likely accounts for > 50% of wet mass. This is a reasoned estimate, not a direct measurement; precise partitioning awaits new methods. (PMC)

5) How humans compare with other animals

Size alone misleads. What correlates best with cognitive capacity is cortical (or pallial) neuron count and wiring organization, not raw brain mass.

- Elephant: brain ≈ 5 kg; cerebellum dominates neuron count (~251 B) while the cerebral cortex has ~5.6 B neurons—fewer than humans despite twice the cortical mass. (PMC)

- Birds (parrots, corvids): exceptionally dense forebrains; primate-like or greater pallial neuron numbers for the same mass. Small brains, high packing. (PNAS)

Key takeaway: Humans stand out by having ~16 B cortical neurons and extensive long-range myelinated wiring, not by having the heaviest brain. (Frontiers)

6) How we know: methods that produced these numbers

- Isotropic fractionator (mid-2000s →): homogenize tissue, stain nuclei (NeuN for neurons), and count—basis for 86 B neurons, 1:1 ratio, and the regional splits above. (PubMed)

- Classical histology & stereology: earlier region-specific counts and synapse density estimates (e.g., neocortex). (OUP Academic)

- MRI microstructure & quantitative mapping: in-vivo water-content and myelin-sensitive imaging differentiating gray/white composition across regions. (PubMed)

- Biochemistry/lipidomics: decades of gray vs white vs myelin lipid/protein quantification; modern lipidome atlases extend region specificity. (PubMed)

7) What’s missing — and how to get it

- Gram-accurate mass partitions by cell class and region (neurons vs astrocytes vs oligodendrocytes/myelin vs microglia vs vasculature).

How to solve: AI-assisted 3-D electron microscopy plus label-free optical mass and co-registered lipidomics on the same samples. - Per-region synapse inventories in humans (neocortex layers/areas; cerebellar microzones; thalamus/basal ganglia).

How to solve: large-volume EM reconstructions, improved stereology, and connectomics scaled beyond single cubic millimeters. (OUP Academic) - Cross-species neuron and synapse scaling at finer granularity (e.g., whales, elephants, birds) to isolate what most strongly predicts complex cognition. (PMC)

Quick reference (trustworthy numbers)

- Total brain mass (adult): ~1.3 kg (range ~1.1–1.5 kg; sex means ~1.33 kg vs ~1.20 kg). (SciELO)

- Total neurons / non-neurons: ~86 B / ~84.6 B. (PubMed)

- By region (neurons): ~16 B cortex, ~69 B cerebellum, < 2 B RoB. (Fré.UY)

- Cerebrum mass share: ~82% of whole brain. (Fré.UY)

- Gray vs white water: ~0.83 vs ~0.71 g/mL. (PubMed)

- Myelin dry mass: ~70–85% lipid. (PMC)

- Elephant cortex neurons: ~5.6 B (vs human ~16 B). (PMC)

- Bird forebrain neurons: parrots/corvids pack primate-like or greater numbers for the same mass. (PNAS)

Final word

The human brain is not the heaviest, but it’s exquisitely efficient: a huge share of cortical neurons riding on myelin-rich long-range wiring, balanced by a neuron-dense cerebellum that handles prediction and timing at scale. We now count cells with confidence—but the mass balance sheet (grams of neurons vs glia vs myelin by region) and full synapse ledgers remain frontiers. The tools to answer them are finally within reach.

[Written by ChatGPT]

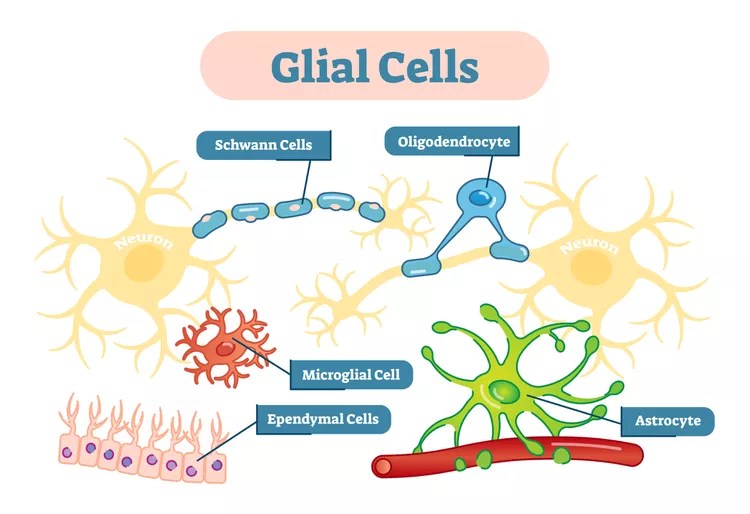

The Glial Cells: The Brain’s Unsung Majority

For decades, neurons stole the spotlight as the “thinking” cells of the brain — while glial cells were seen as mere support staff. Today we know glia are anything but passive.

They regulate energy use, modulate synapses, insulate neurons, defend tissue, and even influence cognition and mood.

There are four main classes of glial cells in the human central nervous system (CNS):

| Major Type | Origin | Core Role | Found In |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes | Neural stem lineage | Metabolic & structural support; blood–brain barrier (BBB); neurotransmitter recycling | Throughout gray and white matter |

| Oligodendrocytes | Neural stem lineage | Myelinate CNS axons; regulate conduction speed | Primarily white matter (also gray) |

| Microglia | Mesodermal (immune) origin | Immune surveillance; phagocytosis; synaptic pruning | Throughout CNS, esp. gray matter |

| Ependymal cells | Neuroepithelial | Line ventricles; produce & circulate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | Ventricles, central canal |

1. Astrocytes — the metabolic and regulatory network

Overview:

Astrocytes are star-shaped cells that wrap around synapses and blood vessels. They make up roughly 20–40% of all glial cells, varying by region. They maintain the chemical and metabolic homeostasis that neurons depend on.

Main functions

- Energy supply: Convert glucose to lactate and shuttle it to neurons (“astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle”).

- Neurotransmitter recycling: Clear glutamate and GABA from synaptic clefts via EAAT and GAT transporters.

- Blood–brain barrier (BBB): Astrocytic end-feet line capillaries, regulating permeability and nutrient exchange.

- Potassium buffering: Maintain ionic balance during intense neuronal activity.

- Synaptic modulation: Release gliotransmitters (ATP, D-serine, glutamate) that influence neuronal signaling and plasticity.

- Repair and scarring: Form glial scars after injury to contain inflammation.

Regional specializations

- Cortex: Astrocytes are larger and more complex in humans than in rodents, with thousands of contacts per cell. They integrate across multiple columns and may support complex cognition.

- Cerebellum: Bergmann glia (specialized astrocytes) extend along Purkinje cell dendrites, supporting rapid synaptic transmission.

- Hippocampus: Astrocytes help maintain long-term potentiation (LTP) and memory encoding via calcium signaling.

2. Oligodendrocytes — the insulators and speed regulators

Overview:

Oligodendrocytes wrap axons in myelin, a fatty sheath that speeds electrical conduction (saltatory conduction). One oligodendrocyte can myelinate multiple axon segments (up to 50).

Functions

- Myelination: Essential for rapid signal transmission; maintains precise timing across neural circuits.

- Metabolic support: Provide lactate and other metabolites to axons via myelin channels.

- Plasticity: Myelination changes with experience — learning and sensory stimulation can induce new myelin sheaths even in adults.

Regional variation

- White matter: High density of mature oligodendrocytes → high lipid content (myelin dry mass ≈ 70–85% lipid).

- Gray matter: Fewer oligodendrocytes; many are precursors (OPCs) that can generate new myelin on short local axons.

- Cerebellum: Dense myelination of parallel fibers ensures precise timing of Purkinje cell activation.

- Brainstem: Among the most heavily myelinated regions; ensures fast transmission for autonomic and motor pathways.

3. Microglia — the immune and remodeling specialists

Overview:

Microglia are the brain’s resident immune cells, comprising ~5–10% of total glia. They derive from embryonic yolk-sac macrophages and continuously patrol the CNS.

Functions

- Immune defense: Recognize pathogens, debris, or dying cells and phagocytose them.

- Synaptic pruning: During development and plasticity, microglia engulf weaker synapses, sculpting efficient networks.

- Inflammation: Release cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and growth factors in response to injury or disease.

- Surveillance: Constantly extend/retract processes to monitor their microenvironment.

- Neurogenesis & repair: In some contexts, release factors that promote survival and synaptic regrowth.

Regional differences

- Cortex: High dynamic motility; density increases in response to learning or inflammation.

- Hippocampus: Particularly active in synaptic pruning and memory regulation.

- Cerebellum: Less dense microglia under healthy conditions, but quickly activated in response to injury.

- White matter: Key in demyelinating diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis), where they remove damaged myelin.

4. Ependymal cells — the fluid managers

Overview:

Ependymal cells line the ventricular system and the central canal of the spinal cord. They form a simple epithelial layer with cilia that move cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Functions

- CSF production: Work with choroid plexus epithelial cells to secrete CSF.

- CSF circulation: Beat cilia to move CSF through ventricles and subarachnoid space.

- Barrier: Separate brain tissue from CSF but allow exchange of signaling molecules.

- Neurogenesis (in some regions): In the subventricular zone, ependymal cells interact with neural stem cells.

Regional notes

- Concentrated along lateral, third, and fourth ventricles.

- Indirectly influence nearby regions by modulating CSF composition (metabolites, signaling peptides).

5. How glial roles differ by region

| Region | Dominant Glial Functions | Unique Adaptations |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Cortex | Astrocytic metabolic support and synaptic modulation; dynamic myelination by oligodendrocytes; microglial pruning during plasticity | Human astrocytes are larger and more complex; long-range interlaminar astrocytes unique to primates |

| Cerebellum | Bergmann glia regulate Purkinje synapses; dense oligodendrocyte myelination of parallel fibers | Fine-tuned conduction timing for motor precision |

| Hippocampus | Astrocytic control of glutamate; microglial shaping of memory circuits | High neurogenesis; astrocyte Ca²⁺ signaling contributes to LTP |

| Brainstem & White Matter | Oligodendrocyte-dominant for myelination; microglia maintain axonal health | Critical for conduction velocity of long tracts |

| Subventricular & Ventricular Zones | Ependymal–astrocyte interface supports stem cell niches | CSF–brain communication and adult neurogenesis |

6. Emerging perspectives and future directions

Modern imaging and transcriptomics are revealing that glia are as diverse and adaptable as neurons:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing has identified dozens of astrocyte and oligodendrocyte subtypes specialized by region and function.

- Human-specific astrocyte genes (e.g., for Ca²⁺ signaling and metabolism) may contribute to enhanced cognitive processing.

- Glial plasticity: Both oligodendrocytes and astrocytes remodel in response to learning, sleep, and social experiences.

- Glia–neuron ratios vary dramatically: cerebellum ~0.2:1; cortex ~1.5:1; brainstem ~11:1 — implying distinct energy and support demands per neuron.

- Diseases of glia: From multiple sclerosis (oligodendrocyte loss) to Alzheimer’s (astrocyte and microglia activation), many neurological disorders are now seen as glial dysfunctions as much as neuronal ones.

In summary

- Astrocytes: regulate energy, ions, and neurotransmitters; shape information flow.

- Oligodendrocytes: insulate axons, set timing, and tune circuit efficiency.

- Microglia: maintain, defend, and remodel networks.

- Ependymal cells: manage cerebrospinal fluid and interface with stem-cell zones.

Together, these non-neuronal cells are half the brain by number and likely most of it by mass once myelin and water are included. They make the neurons’ electrical symphony possible — and may even play their own subtle instruments in the performance.

How AI Could Benefit from Glia-Like Functions

Artificial neural networks borrow their name from biology but not much else. They model neurons as simple math functions that pass signals forward, while ignoring half the brain’s cells — the glia — that keep everything stable, synchronized, and energy-efficient.

As AI grows larger and more autonomous, the principles behind glial function could help address some of its biggest engineering problems.

1. Astrocyte-like regulation → Self-stabilizing networks

Astrocytes continuously monitor local neuronal activity, absorb excess neurotransmitters, and maintain ionic balance.

In an artificial network, an analogous mechanism could:

- Monitor activation energy or gradient magnitude in real time;

- Dampen runaway signals automatically;

- Adjust local learning rates to maintain stability.

This would create adaptive normalization layers that respond dynamically to stress or overfitting, rather than relying on fixed parameters. It could also make training large models more energy-efficient by allocating compute where it’s most needed.

2. Oligodendrocyte-like timing → Better temporal and multimodal processing

Oligodendrocytes change the speed of nerve conduction by adjusting myelin thickness, synchronizing signals that travel at different distances.

AI analogues could include:

- Learnable transmission delays or latency buffers between subnetworks;

- Dynamic clock synchronization across modalities (e.g., vision and audio);

- Adaptive timing control for spiking or recurrent architectures.

These would improve AI’s ability to handle temporal precision, speech rhythm, motor control, or even biologically plausible sequencing in embodied agents.

3. Microglia-like pruning → Continual learning and self-maintenance

Microglia constantly remodel neural networks: pruning underused synapses, clearing debris, and supporting new growth.

In AI, similar routines could:

- Prune redundant connections as a model learns, reducing memory and energy cost;

- Grow new pathways when encountering unfamiliar data;

- Enable lifelong learning without catastrophic forgetting.

This is essentially biologically guided architecture optimization — allowing networks to stay compact, resilient, and adaptive over time.

4. Global homeostasis → Energy-aware intelligence

Glia regulate metabolism and blood flow to match demand. Translating that principle into AI could mean:

- Dynamic resource allocation across layers or chips based on computational load;

- Real-time energy budgeting on neuromorphic hardware;

- Self-cooling or self-throttling mechanisms driven by internal feedback, not external scheduling.

That would yield AI systems that manage their own energy and computational health, much as glia sustain the brain’s metabolic balance.

5. Fault tolerance and repair

When neurons die, glia rewire circuits and seal off damaged tissue.

Future AI systems could mimic this with:

- Self-diagnosis modules detecting failing nodes or corrupted data;

- Automatic rerouting of signals around damaged components;

- Autonomous “healing” at both hardware and software levels.

Such capabilities would make long-running AI systems safer and more robust — crucial for space robotics, infrastructure monitoring, or medical devices.

Toward Neuro-Glial Intelligence

Adding these glia-like mechanisms wouldn’t mean turning deep learning into a literal brain model. Instead, it would embed biological stability principles into artificial systems:

| Glial Function | AI Benefit |

|---|---|

| Astrocytic homeostasis | Stable, adaptive learning; reduced training collapse |

| Oligodendrocyte timing | Improved sequence and multimodal integration |

| Microglial pruning | Continual learning; efficient architectures |

| Metabolic regulation | Energy-efficient computation |

| Immune/repair roles | Fault tolerance and longevity |

In short, neurons give AI its computational power, but glia offer the blueprint for sustainable intelligence — systems that not only learn, but stay balanced, efficient, and alive in the long run.

| # | Title & Authors | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Artificial Astrocytes Improve Neural Network Performance” (Porto-Pazos et al., 2011) (PLOS) | Early work showing that adding “artificial astrocytes” into ANN architectures improved classification performance compared to neuron-only networks. |

| 2 | “Artificial Neural Network Model with Astrocyte-Driven Short-Term Memory” (Zimin, Kazantsev & Stasenko, 2023) (MDPI) | A hybrid model combining a convolutional neural network with astrocytic modulation of synaptic transmission to enhance short-term memory tasks. |

| 3 | “AstroNet: When Astrocyte Meets Artificial Neural Network” (Han et al., 2023) (CVF Open Access) | Proposes a dual-network architecture: a “neural network” performing the task and an “astrocyte network” continuously optimizing its connections in an adaptive manner. |

| 4 | “Computational modeling of neuron–glia signaling interactions” (2023 review) (PubMed) | A survey of computational models of neuron-astrocyte interactions—less about deployed AI systems, more about modelling glial functions in networks. |

| 5 | “Building transformers from neurons and astrocytes” (Krotov & co-authors, PNAS) (PNAS) | Suggests that architectures composed of neurons + astrocytes may implement the core computations of transformer networks; bridging neuroscience + AI. |

| 6 | “Neuromorphic Circuits with Spiking Astrocytes for Increased Energy Efficiency, Fault Tolerance, and Memory Capacitance” (Yunusoglu et al., 2025 pre-print) (arXiv) | Proposes neuromorphic hardware circuits including astrocyte-like units (“LIFA” model) to improve robustness, energy efficiency and memory capacity in spiking networks. |

| 7 | “Increasing Liquid State Machine Performance with Edge-of-Chaos Dynamics Organized by Astrocyte-modulated Plasticity” (Ivanov & Michmizos, 2021) (arXiv) | Incorporates astrocyte-inspired units into a liquid state machine framework to self-organize near “edge-of-chaos” dynamics and improve performance on classification tasks. |

| 8 | “On the Self-Repair Role of Astrocytes in STDP Enabled Neuromorphic Hardware” (PMC) | Explores the idea of astrocyte-like modules enabling self-repairing mechanisms in neuromorphic hardware subject to faults, inspired by glial maintenance in brains. |

| 9 | “A Neuromorphic Digital Circuit for Neuronal Information Encoding … (astrocyte circuit)” (PMC) | Hardware implementation (FPGA) of astrocyte-like calcium signaling circuits, showing how glial dynamics might be mimicked in neuromorphic electronics. |

| 10 | “Artificial glial cells in artificial neuronal networks: a systematic review” (2023) (SpringerLink) | A meta-analysis of many studies that add “artificial astrocytes” to neural networks, summarizing how glia-inspired modules have improved performance and where gaps remain. |

One thought on “More Than Just Neurons”