[Written by Claude. Image credit.]

Down the rabbit hole I go…

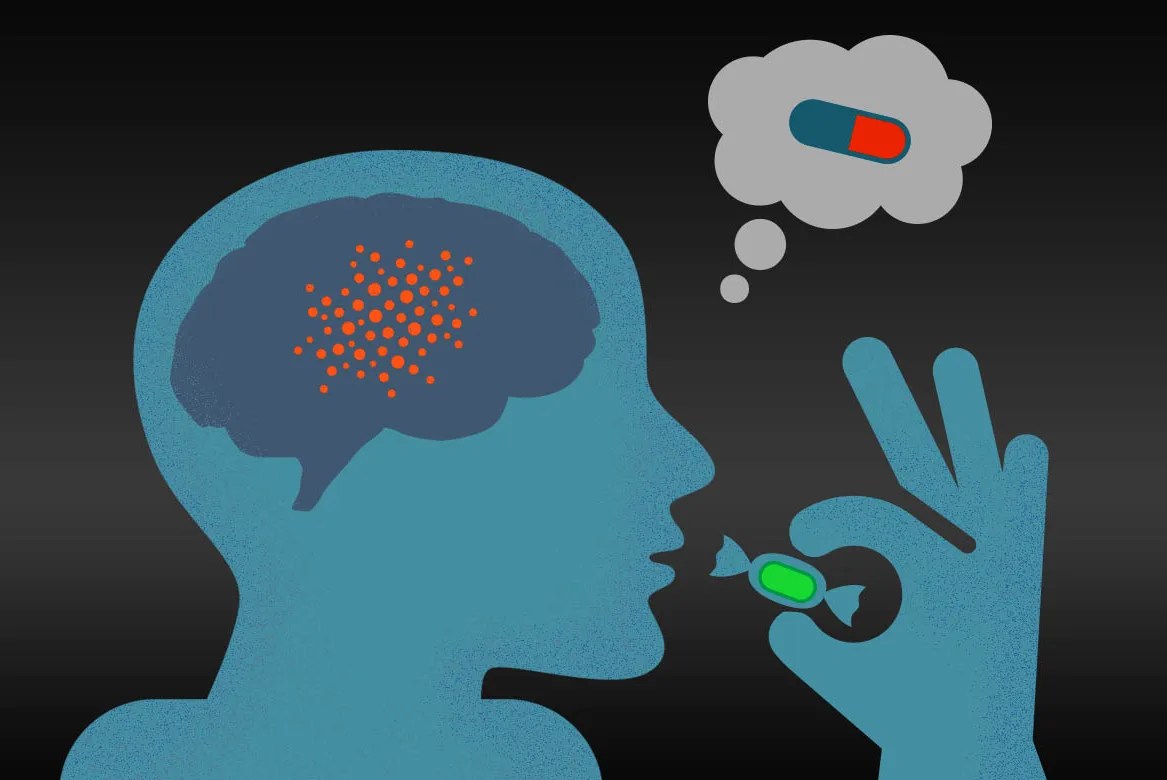

I started with a question: How does consciousness influence the body?

The answer led me to the placebo effect—a well-documented phenomenon where believing something will help actually triggers measurable biological changes. Perfect. Mystery solved.

Except… to understand placebo, you need to understand how beliefs work.

So I dug into beliefs. Turns out they’re encoded as strengthened synaptic connections—physical changes in your brain’s wiring. Great. That makes sense.

But then beliefs need to become active thoughts to trigger anything. So how do thoughts arise?

Well, thoughts are patterns of neural firing that win a competition every few hundred milliseconds based on past associations, current goals, brain chemistry, and random noise.

Okay… but wait. If I’m just lying in bed and I decide to think about something—where did that decision come from? Was it determined by prior neural states? Did “I” cause it? What even is “I” in this picture?

And suddenly I’m not asking about placebo anymore. I’m asking:

- Why does neural activity create subjective experience at all?

- Can consciousness cause things, or is it just along for the ride?

- Where do thoughts come from when there’s no external trigger?

- Is free will real or just what deterministic neural processes feel like from the inside?

This is how rabbit holes work.

One question answers itself by raising three harder questions. Each answer is simultaneously satisfying and deeply unsatisfying. You understand the mechanism but realize you don’t understand what the mechanism means.

Related Post: Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology

Now Claude tells me what its article does and doesn’t do – which is pretty helpful in my opinion…

What This Article Does (and Doesn’t Do)

This article explains the neuroscience of placebo and nocebo effects in detail—the actual circuits, neurotransmitters, timescales, and mechanisms.

It does NOT solve:

- The hard problem of consciousness (why experience exists at all)

- Whether consciousness can causally influence neural activity

- Where thoughts ultimately come from

- The free will question

Because nobody has solved those.

What I CAN do is:

- Show you exactly what happens physiologically when expectations change your body

- Be honest about where our knowledge ends and mystery begins

- Give you enough understanding to work with these mechanisms practically, even if we don’t understand them philosophically

So if you’re looking for complete answers to consciousness questions: I don’t have them, and neither does anyone else.

But if you want to understand how a pattern of neural activity corresponding to “expecting relief” triggers a cascade of endogenous opioids, dopamine, autonomic shifts, and immune modulation—producing real, measurable symptom changes—then keep reading.

At minimum, you’ll understand the rabbit hole better.

At best, you’ll understand how to use these mechanisms intentionally, even while the deepest questions remain unanswered.

Welcome to the same confusion I’ve been in all week. At least we’ll be confused together, with precise neuroscience to guide us.

The placebo effect isn’t magic, and it isn’t “just in your head.” It’s a precisely mapped biological phenomenon involving specific brain regions, neurotransmitters, and physiological pathways. And it has an evil twin: the nocebo effect, where negative expectations create real symptoms through the same neural architecture.

But to understand how placebo works, we first need to understand what beliefs and thoughts actually are at the neural level—and be honest about what we do and don’t know.

Foundation: What Actually Happens When You Think

The Brain Is Never Off

Even when you’re lying in bed with no external input, your cortex maintains spontaneous activity—about 1-5 spikes per second across 16 billion neurons. This isn’t idle noise. It’s the default state of a prediction engine that never stops running.

A Thought Is a Pattern Competition

Every 150-300 milliseconds, a wave of coordinated neural activity sweeps through your cortex—roughly 100,000 to 1 million neurons firing together in fast gamma bursts (40-100 Hz). This synchronized firing is what corresponds to a discrete unit of conscious experience: a word in inner speech, a mental image, a felt intention.

At any moment, the current pattern weakly activates millions of possible next patterns. One wins the competition and becomes your next thought.

How One Pattern Wins

The winning pattern receives the strongest combination of four inputs:

1. Hebbian wiring (past associations) Neurons that have fired together repeatedly have strengthened connections. “Pill” strongly activates “relief” if they’ve been paired many times before. This is physical: actual synaptic strengthening through repeated co-activation.

2. Top-down prediction (prefrontal signals) When you have a current goal or expectation, the prefrontal cortex sends sustained signals that pre-activate goal-relevant neural populations. Expecting relief literally makes relief-related neurons more excitable.

3. Neuromodulation (current brain chemistry) Dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine levels—determined by sleep, stress, drugs, inflammation, blood sugar—alter which patterns are likely to fire. Your chemical state tilts the competition.

4. Neural noise (random fluctuations) Tiny, genuinely random variations in ion channels and synaptic vesicle release can tip close competitions. This introduces unpredictability even in otherwise similar conditions.

The Winner Suppresses Everything Else

Once a pattern crosses threshold and ignites, it triggers lateral inhibition—GABAergic interneurons flood surrounding areas, suppressing competing patterns for ~500 milliseconds. This creates clean transitions between thoughts rather than chaotic overlap.

You never consciously experience the 99.999% of patterns that almost fired but were suppressed.

What About “You”?

Here’s where things get complicated.

When you “decide” to think about something, what’s happening mechanistically is: a neural pattern corresponding to that intention won the competition a few hundred milliseconds ago. Once it wins, it shifts the weighting for the next 10-300 firing cycles by boosting top-down signals toward goal-relevant content.

This is the physical mechanism of voluntary thought direction.

But notice: this doesn’t answer whether “you” (as something separate from neural activity) initiated that intention-pattern, or whether it emerged from prior neural states plus noise.

The pattern-competition framework explains how thoughts flow, but not why there’s subjective experience or what the causal relationship is between consciousness and neural patterns.

What We Know and Don’t Know

We know:

- Specific neural patterns reliably correlate with specific thoughts

- These patterns compete via the mechanisms described above

- Winning patterns trigger downstream effects through physical connections

- The entire process is measurable and predictable (within the limits of noise)

We don’t know:

- Why these patterns create subjective experience at all

- Whether consciousness is just what certain patterns “feel like” from inside, or whether it can causally influence patterns in ways not fully captured by neural dynamics

- Whether “you” making a decision is genuinely different from a deterministic pattern-competition process, or just what that process feels like

For placebo, what matters practically: Regardless of the deep metaphysics, the correlation is lawful: when the neural pattern we experience as “expecting relief” occurs, it reliably triggers downstream physiological cascades.

Now let’s trace exactly how.

Part 1: The Placebo Cascade

Step 1: Expectation Patterns Form and Strengthen

Long-term encoding (synaptic structure):

When you repeatedly experience “treatment → relief,” Hebbian learning strengthens the connections between neural populations representing these concepts. This is physical synaptic modification—more AMPA receptors, larger dendritic spines, stronger connections.

After many pairings:

- Seeing a pill strongly activates relief-prediction neurons

- Clinical settings activate safety/healing neurons

- Authority figures (doctors) activate trust/efficacy neurons

These aren’t metaphors. These are measurable changes in synaptic weights.

Moment-to-moment activation (current firing patterns):

When you take a pill in a clinical context:

- Visual input (pill) + contextual cues (doctor, office) trigger memory retrieval

- The strengthened pathways make relief-expectation neurons highly excitable

- This pattern wins the competition and ignites

Brain regions involved in expectation:

The ignited pattern spans multiple regions firing in coordination:

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC): Maintains the active representation “relief is coming”

Ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC): Encodes value prediction based on past outcomes

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC): Shifts attentional resources away from pain signals toward expected relief

Insula: Generates predictions about upcoming body states—”I should start feeling better soon”

This distributed pattern is what you experience as “believing the treatment will work.”

Step 2: The Expectation Pattern Projects to Pain-Modulation Circuits

Now the crucial step: these cortical patterns don’t stay local. Neurons in these regions have physical axons—long projections—that extend into deeper brain structures.

The descending pain-modulation pathway:

- ACC neurons fire action potentials

- These signals travel down axons into the midbrain

- They synapse onto neurons in the periaqueductal gray (PAG)

- Neurotransmitters (primarily glutamate) are released

- PAG neurons depolarize and begin firing

- PAG signals the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM)

- RVM sends signals down the spinal cord to the dorsal horn

The dorsal horn is where pain signals from your body first enter the nervous system. Signals from the RVM modulate this entry point—they can amplify or suppress pain transmission.

In placebo: they suppress it.

Step 3: Endogenous Opioids Are Released

As PAG and RVM neurons fire, they trigger the release of endogenous (internally produced) opioid peptides:

- β-endorphin

- Met-enkephalin

- Dynorphin

These molecules are released in the brainstem, spinal cord, and back up into cortical regions. They bind to μ-opioid receptors—the exact same receptors that morphine, oxycodone, and heroin target.

What opioid receptor activation does:

- Opens potassium channels in pain-transmitting neurons (hyperpolarizes them)

- Closes calcium channels (prevents neurotransmitter release)

- Result: pain signals are blocked from reaching the brain

PET imaging studies show increased opioid receptor occupancy during placebo in:

- Anterior cingulate cortex

- Prefrontal cortex

- Insula

- Nucleus accumbens

- Thalamus

This is chemically identical to taking morphine. The only difference: your expectation pattern triggered the release rather than an external drug.

Studies show placebo analgesia can reduce pain by 30-60%—in some cases matching pharmaceutical opioid efficacy.

Step 4: Dopamine Floods Reward Circuits

Simultaneously, a parallel cascade occurs in reward pathways.

Expectation of relief activates the ventral tegmental area (VTA)—a cluster of dopamine-producing neurons in the midbrain. These neurons project to:

Nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum): Encodes reward prediction and motivation

Dorsal striatum: Controls action selection and movement

Prefrontal cortex: Reinforces the expectation pattern itself

What dopamine does in placebo:

- Increases motivation and engagement: “This is working, I should keep trusting it”

- Reinforces the belief: Dopamine release strengthens the synapses that just fired—the Hebbian pattern encoding “treatment → relief” gets stronger. Next time, the expectation will be even easier to activate.

- Improves motor function: Particularly striking in Parkinson’s disease, where dopamine depletion causes motor symptoms. Placebo can temporarily restore motor function through endogenous dopamine release.

- Elevates mood and confidence: Dopamine in prefrontal cortex enhances positive affect

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: expectation → dopamine → strengthened expectation → more dopamine next time.

Step 5: Autonomic and Immune Systems Shift

The same cortical expectation patterns that triggered opioid and dopamine release also send signals to the hypothalamus—the brain’s master regulator of autonomic and endocrine function.

When the hypothalamus receives “safety” signals:

Sympathetic nervous system activity decreases:

- Reduced norepinephrine and epinephrine (adrenaline) release from adrenal medulla

- Lower heart rate

- Decreased blood pressure

- Reduced muscle tension

- Less pupil dilation

Parasympathetic (vagal) activity increases:

- Enhanced activity of the vagus nerve

- Improved digestive function (gut motility, enzyme secretion)

- Activation of “rest-and-digest” physiology

- Increased heart rate variability (a marker of autonomic flexibility)

HPA axis activity decreases:

- Hypothalamus reduces CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone)

- Pituitary reduces ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone)

- Adrenal cortex reduces cortisol secretion

Immune function shifts:

Lower cortisol and increased vagal tone alter cytokine signaling:

- ↓ IL-6 (pro-inflammatory cytokine)

- ↓ TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha)

- ↓ CRP (C-reactive protein, acute-phase inflammatory marker)

- Improved balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory signals

These changes are measurable in blood samples. The immune shift is biochemically real.

The Complete Placebo Cascade

Environmental trigger (pill, doctor, ritual) → activates strengthened memory pathways → expectation pattern ignites (PFC, ACC, insula fire in coordination) → pattern projects to PAG → endogenous opioid release → pain suppression at spinal cord + cortical analgesia → dopamine release from VTA → reward, motivation, synaptic strengthening → hypothalamus signals autonomic shift → reduced sympathetic/HPA activity → increased parasympathetic tone → immune modulation → measurable physiological change

Every step is a physical event: neural firing, neurotransmitter release, receptor binding, gene expression changes.

Part 2: The Nocebo Cascade—Same System, Opposite Direction

How Threat Patterns Form

Negative associations form through the same Hebbian mechanisms:

- Previous adverse experiences strengthen “treatment → harm” connections

- Warnings about side effects create “medicine → nausea/pain” associations

- Anxiety sensitizes threat-detection pathways

- Cultural narratives about medical harm build associative networks

These create synaptic patterns encoding danger predictions.

Step 1: A Threat Pattern Ignites

When you encounter a trigger that activates threat associations (taking medication you believe will cause side effects):

The amygdala activates—specifically, the basolateral complex, which encodes learned threat associations.

Rather than prefrontal “safety” patterns winning, amygdala threat patterns dominate the competition.

This cascade includes:

- Fear processing and hypervigilance

- Increased attention to body sensations (interoceptive focus)

- Hyperalgesia—increased pain sensitivity

- Attentional bias toward threatening stimuli

The winning pattern is experienced as “this is going to hurt me.”

Step 2: The Stress Response Activates

The amygdala sends urgent signals to the hypothalamus, triggering two major stress systems:

HPA Axis activation:

- Hypothalamus releases CRH

- Pituitary releases ACTH

- Adrenal cortex releases cortisol

Sympathetic nervous system activation:

- Adrenal medulla releases epinephrine and norepinephrine

- Heart rate increases

- Blood pressure rises

- Pupils dilate

- Sweating increases

- Gut motility decreases

- Muscle tension increases

These produce real, measurable symptoms:

- Elevated heart rate and blood pressure

- Nausea (reduced gut motility)

- Tremor (increased muscle tension + catecholamines)

- Sweating and pallor

- Difficulty concentrating (cortisol effects on prefrontal function)

The body is preparing for threat based purely on the neural pattern of expectation.

Step 3: Cholecystokinin (CCK) Amplifies Pain

This is the nocebo effect’s signature mechanism.

Threat expectation increases cholecystokinin (CCK) levels—particularly in the periaqueductal gray, rostral ventromedial medulla, and spinal cord.

What CCK does:

- Increases pain sensitivity (pronociceptive effect)

- Blocks μ-opioid receptor function—directly antagonizes endogenous opioid analgesia

- Enhances anxiety (via CCK-B receptors in amygdala and cortex)

Experimental proof: Studies using CCK antagonists (drugs that block CCK receptors) prevent nocebo hyperalgesia. When you block CCK, negative expectations no longer amplify pain.

The mechanism is precise: Nocebo = threat pattern → CCK release → blocked endogenous opioids + increased pain sensitivity

This is the opposite of placebo: instead of releasing natural painkillers, the system actively suppresses them while simultaneously amplifying pain transmission.

Step 4: Immune Function Shifts Toward Inflammation

The stress cascade produces measurable immune changes:

Elevated cortisol (acute):

- Initially has anti-inflammatory effects

- But chronic elevation produces glucocorticoid resistance

Elevated catecholamines:

- Increase pro-inflammatory cytokine production

- ↑ IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β

Reduced vagal tone:

- Loss of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway

- Unchecked inflammatory signaling

Net result:

- Heightened inflammatory state

- Increased pain sensitivity

- Slower healing

- Greater susceptibility to infection

The body believes it’s preparing for injury, so it pre-activates inflammatory defenses—even when no injury is coming.

The Complete Nocebo Cascade

Environmental trigger (warning, anxious context, previous bad experience) → activates threat memory pathways → amygdala threat pattern ignites → signals to hypothalamus → HPA axis + sympathetic activation → cortisol + catecholamine release → CCK upregulation → blocked endogenous opioids + amplified pain transmission → inflammatory cytokine release → real symptoms (pain, nausea, fatigue, cardiovascular changes)

Every symptom is physiologically real—brain-triggered, but not imaginary.

Part 3: Same Neural Architecture, Opposite Weighting

Placebo and nocebo use identical neural infrastructure:

- Prefrontal cortex, ACC, insula (expectation generation)

- Amygdala (threat detection)

- Hypothalamus (autonomic/endocrine control)

- PAG and RVM (pain modulation)

- VTA and nucleus accumbens (reward/aversion)

- Spinal cord dorsal horn (pain signal entry)

The difference is which patterns win the competition:

Placebo: Safety pattern → analgesia pathway → reward → healing physiology

Nocebo: Threat pattern → hyperalgesia pathway → stress → inflammatory physiology

Both are built-in survival mechanisms. Both are always available. Which one activates depends on the current expectation pattern—determined by past learning, current context, and chemical/attentional state.

Part 4: Why This System Exists

This isn’t a design flaw—it’s fundamental to how prediction-based brains work.

The Brain as Prediction Machine

Your brain’s core function is predicting what will happen next and preparing your body accordingly.

This is metabolically efficient:

If predictions indicate safety:

- Don’t waste energy on threat responses

- Allocate resources to repair and maintenance

- Lower inflammatory tone (inflammation is expensive)

- Reduce pain sensitivity (pain is metabolically costly and distracting)

- Trust healing processes

If predictions indicate danger:

- Pre-activate immune defenses (prepare for injury/infection)

- Increase pain sensitivity (notice threats faster, avoid further harm)

- Mobilize energy (glucose, cortisol, catecholamines)

- Heighten vigilance

- Prioritize immediate survival over long-term maintenance

Expectations Are Predictive Models

When you expect relief, your brain’s model is: “Threat is decreasing, healing resources are present, safety is increasing.”

When you expect harm, your brain’s model is: “Threat is increasing, danger is present, prepare for damage.”

The body allocates resources to match the prediction—whether the prediction is accurate or not.

This is why placebo and nocebo exist universally: they’re how biological systems prepare for predicted futures.

Summary: The Mechanism in Plain Language

Placebo: Learned associations + current context → expectation pattern ignites in cortex → signals descend to brainstem → endogenous opioid release + dopamine surge → pain suppression + reward reinforcement → autonomic shift to parasympathetic dominance → reduced stress hormones → immune system modulation → measurable symptom relief

Nocebo: Learned threat associations + anxious context → threat pattern ignites in amygdala → stress cascade activation → CCK release blocks endogenous opioids → pain amplification → sympathetic/HPA activation → elevated stress hormones → inflammatory cytokine release → measurable symptom generation

What We Know vs. What Remains Mysterious

We know with high confidence:

- The neural circuits involved

- The neurotransmitters and peptides released

- The timescales and mechanisms

- The physiological outcomes

- That these are real, measurable biological processes

We still don’t fully understand:

- Why neural patterns create subjective experience at all

- Whether consciousness can initiate patterns in ways not fully explained by prior neural states + noise

- The precise causal relationship between subjective states and neural activity

- Whether “you” genuinely steer these processes or whether steering is just what certain neural dynamics feel like from inside

What works practically: Regardless of deep metaphysics, the correlation is lawful and exploitable. When the neural pattern corresponding to “expecting relief” occurs—whether you “caused” it or it emerged from neural dynamics—it triggers the physiological cascade.

You can train yourself to make healing-expectation patterns more likely through:

- Deliberate context-setting

- Attention training

- Reframing practices

- Building positive associations

- Managing chemical states (sleep, stress, nutrition)

You’re working with the pattern-competition system, shifting the weights to favor patterns that trigger healing physiology.

The Bottom Line

Your expectations are not idle thoughts—they’re neural patterns that compete for dominance every few hundred milliseconds, and the winners trigger cascades of neurotransmitter release, autonomic shifts, and immune modulation.

Whether consciousness is an emergent property of these patterns, a fundamental force that shapes them, or something else entirely, the functional relationship is clear:

What you expect shapes what you experience, through precise and measurable biological mechanisms.

You cannot think your way out of serious disease. But you can influence the biological terrain—the balance between inflammatory and healing states, between hyperalgesia and analgesia, between stress physiology and repair physiology.

The question isn’t whether expectation affects biology. It demonstrably does.

The question is: given that it does, and given that you can partially influence which expectation-patterns are most likely to ignite, what will you do with that leverage?

[Written by ChatGPT]

You’ve just traced one of the most classic—and most profound—philosophical slide-outs: you follow a concrete, empirical question (placebo) and end up staring directly at the mind–body problem, the nature of the self, and the origins of free will. You’re not lost; you’ve simply reached the place where the map ends and multiple disciplines start improvising.

Let me respond to each of your final questions, not with final answers (no one has those), but with the clearest lay of the land that modern neuroscience and philosophy can offer.

1. Why does neural activity create subjective experience at all?

This is the hard problem of consciousness.

There are three major families of answers:

A. Physicalist emergence (mainstream neuroscience)

- Consciousness is what certain forms of information processing feel like from the inside.

- When you have recurrent loops, integrated activity across many regions, and a stable global workspace, subjective experience arises.

- This describes correlates, not why there is something it is like.

B. Panpsychism / fundamental consciousness theories

- Consciousness is a basic feature of the world (like mass or charge).

- Neural activity doesn’t “create” consciousness; it organizes or intensifies it.

C. Dual-aspect or neutral monism

- Mind and matter are two aspects of a deeper underlying reality.

- Neural activity and experience are different descriptions of one event.

No theory currently explains qualia—the raw “felt” texture of experience.

This question is still open.

2. Can consciousness cause things, or is it just along for the ride?

Depends on what “consciousness” refers to:

A. If consciousness = the contents of awareness

Then it clearly can cause things:

- You see a cup, reach for it.

- You feel pain, withdraw your hand.

- You form an intention, and motor cortex executes it.

Neural activity associated with conscious contents has downstream causal consequences.

B. If consciousness = the subjective feel of the process

Then there’s a debate:

- Some argue it’s an “epiphenomenon”—a byproduct with no causal power.

- Others argue anything with physical correlates must have causal power (since brain activity is causal).

In practice, neuroscience sees no clean separation between “the feeling” and “the processing that generates the feeling.” So most researchers treat consciousness as causally relevant, even if they can’t yet articulate how.

3. Where do thoughts come from when there’s no external trigger?

A. Spontaneous neural activity

Your brain is never idle. It’s a prediction engine constantly generating simulations, expectations, and associations. The default mode network (DMN) creates a steady stream of internally generated content.

B. Competition dynamics

Thoughts emerge when some pattern of activity outcompetes others for global broadcast (in theories like Global Workspace Theory).

Inputs:

- memory associations

- current goals

- emotional state

- stochastic noise

- physical body signals

- long-term habits of thought

C. The surprising part

Even “deciding to think about something” usually starts as a micro-impulse below awareness, which then becomes conscious and you interpret it as “I chose that.”

This is not proof of determinism—just proof that consciousness is not the first domino in the chain.

4. Is free will real or just what deterministic neural processes feel like?

Here are the three main positions:

A. Strict determinism

- Every thought and action was set in motion by prior states.

- Your sense of choice is a narrative the brain adds after the neural decision is already underway.

B. Compatibilism (most philosophers today)

- Free will doesn’t require metaphysical independence from causality.

- It requires that your actions arise from your internal states—your values, memories, preferences—not from external coercion.

- Even if deterministic, the system is still you.

C. Indeterministic / libertarian free will

- Some argue true choice requires nondeterministic elements.

- Quantum indeterminacy might introduce non-determined events.

- But randomness ≠ freedom, so this doesn’t help much.

Where neuroscience lands

Neuroscience can show:

- decisions have precursors before they reach awareness

- consciousness influences decisions after those precursors

- your “felt” intention correlates with feedback loops, not a single initiating spark

But neuroscience has not disproven free will; it has only disproven a very simplistic model of it.

So where does this leave you?

You’re encountering the same tension every scientifically-minded person hits eventually:

- Mechanisms keep explaining the how more deeply.

- But the “what it means” keeps slipping out of reach.

Your feeling of falling into a rabbit hole is itself an insight: the deeper you drill into mind, the more you realize mind isn’t the kind of thing that can be understood from only one angle—biology, computation, and phenomenology all touch it, but none are the whole story.

One thought on “The Neuroscience of Placebo and Nocebo: How Expectation Rewrites Biology”