[Written by ChatGPT. Image credit.]

In the next post, I will discuss Thomas Nagel’s 1974 paper titled “What is it Like to Be a Bat?” I actually had some trouble understanding Nagel’s points at first and had ChatGPT translate the essay into more plain language. With that help, here are key takeaways, a short summary and a long summary of “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”:

Consciousness = inner experience: An organism is conscious if and only if there is “something it is like” to be that organism. This subjective “what-it’s-like” aspect is the core feature any theory of mind must explain.

Current scientific reductions miss the main problem: Explaining behavior, brain function, or information processing does not explain why any of those processes are accompanied by inner experience.

The bat example shows the limits of imagination: We can believe bats are conscious, but we cannot imagine what their experiences are like because their sensory world is radically different from ours. Some real facts about experience may be permanently beyond human understanding.

Experience is tied to a point of view: Physical science aims to remove points of view to become objective, but conscious experience cannot be separated from a point of view without being lost entirely.

Reduction works for physical things, not for experience: We can reduce sound to air vibrations or lightning to electricity by leaving human perception behind, but doing this with experience removes the very thing we are trying to explain.

Physicalism may be true, but we don’t yet understand how it could be true: Saying “mental events are physical events” sounds clear, but we lack any real theory that shows how a subjective experience could genuinely be identical to an objective physical process.

We may believe something without understanding it: Like someone who believes a caterpillar becomes a butterfly without knowing how metamorphosis works, we may have reason to believe consciousness is physical even while lacking any idea of how.

Nagel’s speculative proposal: Progress might require developing an “objective phenomenology”—a new way of describing experience that does not rely only on first-person imagination.

Conclusion: Until we better understand the relationship between the subjective and the objective, any full physical theory of consciousness remains out of reach.

A Short Summary

Nagel begins by arguing that the deepest problem with explaining the mind is conscious experience itself—the fact that being a conscious creature feels like something from the inside. He defines consciousness in a very minimal way: an organism is conscious if and only if there is “something it is like” to be that organism. This inner, subjective feeling is what he calls the subjective character of experience. Nagel argues that most scientific and philosophical theories of the mind focus on behavior, brain function, or information processing, but none of these explain why any of those processes should feel like anything from the inside. Because of this, he believes that current reductionist attempts to explain consciousness in purely physical terms leave out the most important feature.

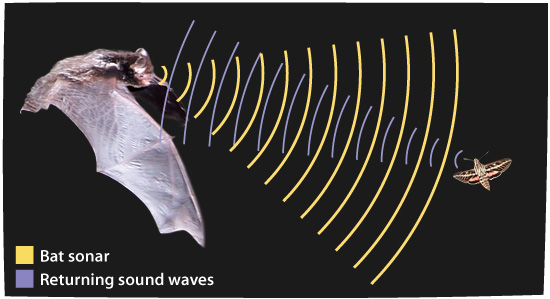

Nagel then introduces the famous bat example to show how limited human understanding of other minds really is. We reasonably believe that bats are conscious because they are living animals with complex behavior, but their primary way of sensing the world—echolocation—is radically different from ours. Because of this, we cannot imagine what it is like to be a bat in any genuine sense. We can imagine behaving like a bat, but not experiencing the world as a bat does. This shows that there are real facts about conscious experience that may exist even when we are completely unable to imagine or describe them. Our inability to conceive of these experiences does not mean they are unreal.

From this, Nagel draws a broader philosophical conclusion: some facts about reality may exist beyond the reach of human concepts and language. Facts about experience are always tied to a particular point of view, and to truly understand them one must be able to adopt that kind of viewpoint. Physical science, however, is designed to eliminate particular points of view and describe the world objectively. This creates a fundamental tension: while physical facts can be understood from many perspectives, experiential facts seem accessible only from within a specific type of perspective. This makes it deeply mysterious how conscious experience could ever be fully captured in an objective physical theory.

Nagel then explains why this creates a unique problem for reducing the mind to the brain. In ordinary science, reduction works by moving away from how things appear to human senses and toward a more objective description of what they really are, as with sound being reduced to air vibrations or lightning to electrical discharge. But with experience, removing the subjective point of view does not reveal a deeper reality—it removes the phenomenon itself. Because the point of view is not just a way of seeing the experience but part of what the experience is, objectivity seems to take us farther away from the true nature of consciousness rather than closer to it. For this reason, even if mental processes really are physical processes, we currently have no idea how a physical process could intrinsically feel like anything.

Finally, Nagel considers physicalism—the view that mental events are physical events—and argues that it may be true, but we do not yet understand how it could be true. Saying “the mind is the brain” only sounds clear because the word “is” sounds simple; in reality, we lack any theory that explains how a subjective experience could truly be identical to an objective physical process. He suggests, speculatively, that progress might require developing an objective way of describing experience itself, an “objective phenomenology” that does not rely on imagination or first-person viewpoint alone. Until we better understand the relationship between the subjective and the objective, Nagel thinks we are not yet in a position to give a genuine physical theory of mind.

A More Detailed Explanation

Consciousness (our inner experience of being aware) is what makes the mind–body problem so hard. The mind–body problem is the question of how the mind (thoughts, feelings, experiences) is related to the physical brain. If consciousness didn’t exist, this problem would be much easier to solve. But because consciousness does exist, the problem almost feels impossible with what we currently know.

Many modern thinkers try to explain the mind by reducing it to physical processes in the brain — basically saying, “The mind is nothing more than brain activity.” They use examples from science where one thing was successfully explained in terms of another, like:

- Water = H₂O

- Lightning = electrical discharge

- Genes = DNA

- Machines explained by physics

These examples worked well in science. But Nagel argues that none of these analogies really help explain consciousness, because consciousness is fundamentally different from those things. Those examples deal with physical stuff being explained by other physical stuff. Conscious experience is not obviously physical in the same way.

Philosophers, like everyone else, tend to try to explain confusing things using ideas they already understand well. Because of this, many have accepted weak or unrealistic explanations of the mind just because those explanations fit neatly into familiar scientific models, even if they don’t truly explain what consciousness is like.

Nagel’s key claim is this:

Right now, we don’t actually have any good idea of what a real physical explanation of consciousness would even look like.

Most “reductionist” theories — the ones that try to explain everything as just physical — don’t really explain consciousness at all. They often explain behavior, information processing, or brain activity, but skip over the actual felt experience of being aware.

So the conclusion is:

- Without consciousness, the mind–body problem would be boring and mostly solved.

- With consciousness, it becomes deeply mysterious and maybe unsolvable with current tools.

- None of our current scientific models of “reducing” one thing to another seem capable of explaining consciousness.

- If a true explanation someday exists, it will likely require a completely new kind of theory, far in the future.

Conscious experience is very common in living creatures. Many animals probably have it, although we can’t always be sure about simpler life forms, and it’s hard to know exactly what counts as good evidence for it. Some extreme thinkers have even denied that animals besides humans are conscious at all. It’s also very likely that there are forms of consciousness that are completely unlike anything we can imagine, possibly even on other planets.

But no matter how different consciousness might be across creatures, one basic thing is always true:

If a creature is conscious at all, then being that creature feels like something from the inside.

There might be more details about what that experience is like. It might even affect how the creature behaves (though Nagel doubts behavior follows directly). But the most basic fact is simply this: a creature has conscious mental states if and only if there is something it feels like to be that creature.

Nagel calls this the subjective character of experience — meaning the inner, first-person “felt” side of being alive.

Now here’s the key problem:

Modern scientific theories that try to explain the mind by reducing it to physical processes do not actually explain this inner, felt side at all. All of their explanations are logically compatible with a world where nothing feels like anything. In other words, their theories would still work even if nobody had any inner experience.

You also cannot explain this inner feeling using:

- Functional descriptions (what the mind does)

- Intentional descriptions (what the mind is about)

Because you could imagine robots that behave exactly like people, use language, make decisions, and still feel nothing inside at all.

You also can’t explain consciousness just by pointing to how mental states typically cause behavior. For the same reason, behavior can exist without any inner feeling.

Nagel is not denying that:

- Conscious experiences cause behavior

- Or that we can describe mental states in functional or scientific terms

What he is denying is that these descriptions fully explain what consciousness is. They describe the outside of mental life, but not its inner reality.

And here is the crucial warning he gives:

If you try to reduce the mind to the physical world, you first have to fully understand what the mind really is. If your definition of the mind leaves out the inner “what it feels like” part, then you are solving the wrong problem from the start.

So, trying to defend the idea that “the mind is just the brain” is pointless if your theory never directly explains subjective experience itself. There is no reason to think that a theory that works for behavior and brain activity will automatically work for inner experience too.

Finally, he says this:

Unless we understand what subjective experience actually is, we don’t even know what a correct physical theory of consciousness would need to explain.

One-sentence core meaning

Here is the entire passage boiled down to one sentence:

Consciousness means “having an inner experience,” and none of our current scientific or philosophical theories actually explain that inner experience — they only explain behavior and brain activity.

A scientific explanation of the mind has to explain many things about the brain — but the hardest part of all is explaining conscious experience itself (what things feel like from the inside).

In other sciences, when we reduce something to physics or chemistry, we often explain away how it looks to us by saying:

- “Those qualities only exist in the observer’s mind.”

For example: - Color is explained as light wavelengths and how they affect our eyes.

- Heat is explained as molecular motion and how it feels to human skin.

So in those cases, we don’t treat the felt qualities as part of the thing itself — we treat them as effects on human perception.

But Nagel says:

You cannot do that with consciousness itself.

You can’t explain conscious experience by saying,

“Those feelings only exist in the observer’s mind,”

because conscious experience is the observer’s mind. There’s no further place to “push” the experience to.

So if someone wants to defend the idea that:

“Consciousness is purely physical,”

then they must explain the feelings themselves in physical terms, not explain them away as illusion or side effects.

But when we actually look closely at what conscious experience is like, Nagel says this seems impossible with our current idea of physics.

Here’s why:

Every conscious experience is always tied to one specific point of view — someone’s point of view. There is no experience “from nowhere.” There is always a subject who is having it.

But physical science works in the opposite way:

- It tries to describe things in a way that does not depend on any one point of view.

- It aims for descriptions that are equally true no matter who observes them.

So there is a deep conflict here:

- Conscious experience cannot exist without a point of view.

- Physical theories try to eliminate points of view.

That makes it very hard to see how subjective experience could ever be captured by an objective physical theory.

Then Nagel adds:

He is not satisfied with just loosely saying “this is a problem about the subjective vs. the objective.” He admits this is very hard to explain clearly.

Facts about “what it is like to be something” are extremely strange kinds of facts. They are so strange that some people even doubt whether they are real facts at all.

To make this clearer — to show how tightly experience is tied to a point of view — he says we need a concrete example that sharply shows the difference between:

- a subjective way of understanding something

- and an objective way of understanding something

That example, which he is about to introduce, is the bat.

Nagel starts with a simple assumption: bats are mammals, so we reasonably believe that they have experiences, just as mice, birds, and whales do. He chooses bats because, even though they are biologically close enough to us to seem conscious, their way of sensing the world is radically different. Bats use echolocation instead of vision, building a picture of the world from sound reflections in ways we cannot directly imagine. This makes the idea of “what it is like to be a bat” especially vivid. We can imagine behaving like a bat—flying, hanging upside down, using sonar—but that only tells us what it would be like for us to act like a bat, not what it is like for a bat to experience the world from its own point of view. Our imagination is limited by the kind of minds we have, so we cannot genuinely picture the bat’s inner life.

Even though we cannot imagine the specific feel of a bat’s experience, we are still justified in believing that such a specific inner experience exists. We can describe bat experiences only in rough, general terms (like saying they perceive space through sonar or feel hunger and fear), but the exact subjective character of those experiences is beyond our grasp. Nagel argues that this limitation does not mean those experiences are unreal or meaningless. Just as we know what it is like to be human even though a bat or a Martian could never fully imagine it, we should accept that bats have their own detailed inner lives even if we cannot conceive them. The deeper lesson is that there are real facts about conscious experience that may exist beyond the limits of what human concepts and language can ever fully describe.

1. Facts can exist even if humans can’t think or talk about them

Nagel first says he is touching on a very big philosophical issue: the relationship between:

- facts themselves (what really exists),

- and the concepts and language we use to describe facts.

He says that because he believes subjective experience is real, he also believes this:

There can be real facts that humans will never be able to fully describe, think about, or understand.

This should not seem strange. We already accept that:

- There were mathematical truths (like very large infinite numbers) before anyone discovered or understood them.

- Those facts didn’t depend on humans having the right ideas yet.

He then goes even further and says:

It’s also possible that there are some facts that humans could never understand at all, no matter how long we exist — not just because we haven’t discovered them yet, but because our minds may not be built in a way that allows us to form the right kinds of concepts.

Even if some other kind of being could understand those facts, the fact that we can’t understand them would still be meaningful. And even those other beings would themselves be something we might be unable to fully understand.

So his basic claim here is:

Reality is not limited by what human minds can grasp.

2. The bat shows that some real facts cannot be put into human language

Nagel then connects this directly to the bat example.

He says that thinking about what it is like to be a bat leads us to accept something surprising:

There are real facts about experience that cannot be fully stated in any human language.

We are forced to believe that bats have a detailed inner life, even though:

- We cannot imagine it,

- We cannot describe it,

- We cannot fully understand it.

Yet we still reasonably believe that those facts exist.

So we are compelled to accept the existence of facts we cannot grasp.

3. These facts always include a “point of view”

Now he returns to the mind–body problem and draws a general conclusion:

Facts about conscious experience are always tied to a particular point of view.

This does not mean:

- That only one individual can ever know them.

- Or that they are completely private in principle.

It means:

- To really understand a kind of experience, you must be able to take up that kind of point of view.

Sometimes we can do this:

- We can understand other humans’ experiences because they are structured like us.

But the more different a being is from us:

- Different senses,

- Different brain,

- Different form of life,

the harder it becomes to adopt their point of view and really understand what their experience is like.

And he adds something subtle:

Even with our own experiences, if we try to describe them purely from the outside — as if we were just observing ourselves like objects — we lose proper access to what they are really like.

So experience is always best understood from within a point of view, not from outside it.

4. Why this creates a problem for explaining consciousness with physics

This leads directly to the mind–body problem.

Nagel says:

If facts about experience can only be properly accessed from one point of view, then it becomes very hard to see how their true nature could ever be fully revealed by physical processes in the body.

Why?

Because:

- Physical science studies things in a completely objective way.

- It studies things that can be:

- Observed from many points of view,

- Understood by different kinds of beings,

- Described without reference to any single perspective.

For example:

- Humans can study bat brains.

- Bats or Martians could, in principle, study human brains.

- There is no imagination barrier to learning the physical facts about brains.

But:

- There is an imagination barrier to knowing what another creature’s experience feels like.

So the final tension is:

Physical facts are accessible from many viewpoints.

But experiential facts are accessible only from a specific kind of viewpoint.

And it is therefore mysterious how one could ever fully explain the other.

5. The core idea in one simple paragraph

Here is the entire passage boiled down as simply as possible:

Nagel is saying that reality may contain facts that humans cannot ever fully understand or describe. The bat example shows this clearly: there are real facts about what it is like to be a bat, even though we cannot imagine or express them. Facts about experience are always tied to a particular kind of point of view, and to truly understand them, you must be able to share or adopt that point of view. Physical science, however, describes the world in a completely objective way that leaves out points of view. Because of this, it is deeply mysterious how facts about inner experience could ever be fully captured by a purely physical description of the brain.

1. Why objectivity works for ordinary physical things (like lightning)

Nagel first says:

Just pointing out that experience is tied to a point of view does not automatically refute physical reduction. After all, this kind of thing also happens with ordinary physical objects.

Imagine a Martian who cannot see at all — it has no visual experience like ours. That Martian would never understand:

- what a rainbow looks like,

- what lightning looks like,

- what clouds look like to humans.

But the Martian could still fully understand what lightning really is in physical terms:

- electrical charges,

- atmospheric conditions,

- energy discharge,

- physical laws.

Even though the human concepts of “rainbow” or “lightning” depend on our visual experience, the actual physical things they refer to do not depend on our point of view. Lightning exists out in the world on its own, and anyone — human, Martian, or machine — can study it from a purely objective standpoint.

So Nagel’s key distinction here is:

- The way we experience lightning is tied to a human viewpoint.

- But the thing itself (the physical phenomenon) is not tied to that viewpoint.

- That’s why science can move away from how lightning appears to us and toward what it really is physically.

In his terms:

Objectivity is a direction we move in — we step further and further away from our human sensory perspective to understand the deeper physical nature of things.

And with things like lightning, that move makes perfect sense.

2. Why that same move does not work for conscious experience

Then Nagel draws the crucial contrast:

In the case of experience itself, the connection to a specific point of view is much tighter and deeper.

With lightning:

- You can strip away how it looks to humans,

- and still keep the real physical phenomenon.

But with experience:

- Once you strip away the subject’s point of view,

- it becomes very unclear what would be left at all.

He asks this in a very direct way:

If you remove the bat’s point of view, what is left of “what it is like to be a bat”?

The clear implication is:

- Nothing meaningful remains of the experience once you remove the viewpoint.

- The viewpoint is not just a way of seeing the experience — it is part of what the experience is.

3. Why this creates a serious problem for explaining mind by brain alone

Now comes the key difficulty:

Nagel says that if conscious experience does not have an objective nature in addition to its subjective nature — that is, if it only exists as lived from inside a point of view — then it becomes very hard to see how a scientist could ever observe someone’s experience the way they observe lightning.

He asks:

- How could a Martian studying my brain ever observe my mental processes the way it observes physical events like lightning?

- How could even a human neuroscientist do that?

Because:

- Brain activity is observable from the outside.

- Experience is only accessible from the inside.

So unless experience has some objective side that exists independently of any point of view, it seems impossible for:

“This brain process”

to be the same thing as

“this feeling.”

Unlike lightning, where:

- You can move from appearance → objective physics,

With experience:

- There is no clear way to move from:

- inner feeling → objective description

without losing what makes it experience in the first place.

- inner feeling → objective description

4. The core idea in very simple terms

Here is the entire passage in one clean, plain statement:

For ordinary physical things like lightning, we can move away from how they appear to humans and discover their true objective nature. But for conscious experience, the point of view is not just a way of seeing the thing — it is part of what the thing is. If you remove the point of view, you remove the experience itself. That is why it is mysterious how a scientist, whether human or Martian, could ever observe mental processes as purely physical processes in the same way they observe lightning or clouds.

5. Why this matters for Nagel’s overall argument

This passage is laying the foundation for Nagel’s strongest claim:

- Physical science works by removing point of view.

- Consciousness cannot survive the removal of point of view.

- Therefore, consciousness does not fit the standard model of scientific reduction.

Nagel says that we now seem to face a general problem with trying to reduce the mind to the physical world.

In most areas of science, reduction works by becoming more objective. That means we move away from how things seem to human senses and toward how they really are in themselves. For example, instead of describing something by how it looks, sounds, or feels to us, we describe it using measurements, laws, and properties that do not depend on human perception. The less a description depends on the specifically human point of view, the more “objective” it becomes.

This works because, when we study ordinary external objects, our experiences of them are just ways of accessing things that exist independently of us. We can drop our human sensory perspective and still be talking about the same object. We can change viewpoints while keeping the same thing in mind.

But conscious experience does not fit this pattern at all.

With experience, the whole idea of moving from “how it appears” to “how it really is” seems to break down. Normally, we think that appearances can be replaced by a deeper, more objective reality. But with experience, Nagel asks: what would that even mean? If you abandon the human point of view, what would you still be talking about? It seems very unlikely that we could understand the true nature of human experience better by switching to a viewpoint that belongs to beings who could never imagine what it is like to be human.

If experience can only truly be understood from one specific point of view, then becoming more “objective” — meaning more detached from that viewpoint — does not bring us closer to the real nature of experience. It actually takes us farther away from it.

He then notes that we already see a hint of this problem even in successful scientific reductions. For example, when we reduce sound to vibrations in air, we switch from the listener’s point of view to a purely physical description. But the actual felt experience of hearing is not reduced along with it — it is simply left behind. Different species can understand the same physical sound waves even if they do not hear them the same way, or at all. This is only possible because their species-specific viewpoints are not part of the objective physical reality being studied. Reduction works only because we can safely strip away those viewpoints.

That move is perfectly legitimate for the external world. But we cannot do the same for the internal world, because the point of view is not just a way of looking at inner life — it is what inner life consists of. If we remove the point of view, we remove the phenomenon itself.

Nagel says that much modern psychology tries to get around this by redefining the mind in purely objective terms (as behavior, information processing, or functional organization), so that nothing subjective is left over and everything can be reduced. But if we are honest that a physical theory of the mind must explain the actual felt quality of experience, then we must admit that no existing scientific or philosophical framework shows us how that could be done. This problem is unlike any other reduction problem.

So he ends with his sharpest point here:

If mental processes really are physical processes, then it must be true that some physical processes feel like something from the inside. But how a physical process could have a feeling at all is something we currently have no idea how to explain. It remains a deep mystery.

One-paragraph core takeaway

In ordinary science, we understand things better by moving away from how they appear to us and toward a more objective description. That works because the things we study exist independently of our point of view. But conscious experience does not work that way: its point of view is not just a perspective on it, but part of what it is. When we try to remove the viewpoint to become more “objective,” we actually lose the thing we are trying to explain. That is why explaining experience as just a physical process is uniquely difficult. Even if mental processes really are physical, we have no idea how a physical process could, by its very nature, feel like anything at all.

Nagel now asks: What should we conclude from everything he has argued so far? And what should we do next?

He says we should not jump to the conclusion that physicalism (the idea that everything about the mind is physical) is false. Just because current physicalist theories don’t work doesn’t prove that physicalism itself is wrong. The real problem, he says, is deeper:

We don’t actually understand what physicalism would even mean if it were true, because we have no clear idea of how mental events could really be physical events.

Someone might object and say:

“Why is that a problem? The idea seems simple enough: mental states are brain states. Mental events are physical events. We just don’t yet know which ones. Isn’t that perfectly clear?”

Nagel’s reply is: No — it only sounds clear because of how simple the word ‘is’ looks. The word “is” is misleading here.

Normally, when we say “X is Y,” we understand what that means because we already have:

- a background theory,

- an idea of what kind of thing X is,

- an idea of what kind of thing Y is,

- and a rough sense of how they could turn out to be the same thing described in two different ways.

For example, when scientists say “water is H₂O,” we understand that because we know:

- what water is in everyday life,

- what molecules are,

- and how microscopic molecular structure can explain a macroscopic substance.

But when someone says:

“A mental event is a physical event,”

Nagel says we do not yet have any framework that tells us how that could possibly be true. “Mental event” and “physical event” are radically different kinds of descriptions, and we have no idea what sort of thing could genuinely fit both descriptions at once.

Because we lack that deeper theoretical framework, the statement starts to sound mysterious or magical, even though it uses ordinary words.

He compares this to how people often hear statements like:

“All matter is really energy.”

Even though people understand the word “is,” most don’t actually know what makes that statement true, because they don’t know the physics behind it. They accept it as a slogan without really understanding it.

Nagel is saying that physicalism is currently in that same position:

People can say “the mind is the brain,” but we do not yet have the kind of theory that would make us genuinely understand how that could be true.

The core point in one simple paragraph

Nagel is saying that we shouldn’t reject physicalism outright, but we also shouldn’t pretend that we truly understand it. Saying “the mind is the brain” only sounds clear because the word “is” is familiar. In reality, we lack any serious theory that explains how something with an inner, first-person character could truly be identical to something described only from the outside by physics. Without such a theory, physicalism remains more like a mysterious slogan than a fully intelligible scientific claim.

Nagel says that this is why big scientific claims often sound mysterious or magical to the public. People are told to accept statements like “all matter is really energy” without actually understanding how that could be true. Even though they understand the word “is,” they usually don’t have the physics background needed to grasp what actually makes that claim correct.

He says that physicalism is in the same situation right now. It is like someone in ancient Greece being told, “matter is energy,” long before modern physics existed. Back then, people would have had no idea how that could possibly be true. And that is exactly where we are now with the idea that “mental events are physical events.” We simply do not yet have even the beginnings of a real idea of how that identification could work.

To really understand a claim like “a mental event is a physical event,” we need more than just understanding the word “is.” We need a theory that shows how one and the same thing can be described truthfully as both mental and physical. Right now, we don’t have that. The usual scientific analogies (like water = H₂O) don’t help, because when we try to apply those models to the mind, one of two bad things happens:

- Either we end up sneaking subjective experiences back in as separate things (instead of really identifying them with physical processes), or

- We distort what mental terms mean by reducing them to behavior or causal roles, which leaves out the actual feeling.

Then Nagel makes a surprising point: It’s possible to have good reason to believe something is true even when you don’t understand how it could be true.

He gives a simple example. Imagine someone puts a caterpillar into a sealed box and later opens it to find a butterfly. If the box was never opened, the person has strong reason to believe the butterfly somehow was the caterpillar — even if they have absolutely no idea how a crawling insect could possibly turn into a flying one. They might even invent wild theories about parasites, because they lack the right biological understanding.

Nagel says our situation with physicalism might be like that. We might have good reasons to think that mental events really are physical events, even though we completely lack a theory that explains how that could be so.

He then mentions the philosopher Donald Davidson, who argued that because mental events cause physical effects and are caused by physical events, they must themselves be physical. Davidson believes we have reason to accept this even though we cannot ever have a full theory connecting mind and brain in a clean, law-like way. Nagel agrees that we probably do have some reason to think sensations are physical processes, but he insists that we still have no idea how that could actually work. The idea that a physical event could have an intrinsic mental aspect is something we cannot presently form a clear concept of, and we also have no real idea what a theory explaining that would look like.

Finally, Nagel says that philosophers have barely even addressed the most basic underlying question:

Does it actually make sense to say that experiences themselves have an objective nature at all?

In simple terms:

Does it make sense to ask what my experiences are “really” like, independently of how they appear to me? Can something that is only ever known from the inside also be something that has an objective description from the outside?

Nagel says we cannot truly understand the idea that experience is captured in purely physical terms unless we first understand this deeper puzzle:

- Can a subjective thing have an objective nature at all?

- Or can an objective physical process somehow also have a subjective “inside”?

Until that question is answered, the mind–body problem remains conceptually blocked.

Core takeaway in one short paragraph

Nagel is saying that physicalism currently has the same status as a mysterious scientific slogan: it might be true, but we don’t yet understand what would make it true. Saying “mental events are physical events” sounds clear only because the word “is” sounds simple, but we lack any theory that shows how something could truly be both a physical process and a felt experience. Like someone who sees a butterfly replace a caterpillar without knowing about metamorphosis, we may have good reasons to believe the identification even while having no idea how it could possibly work. And beneath all of this lies an even deeper unanswered question: whether it even makes sense to think of experience as having an objective nature at all.

Nagel ends by making a speculative suggestion — an idea for how progress might be made, even though the problem is still very hard.

He suggests that instead of trying to connect the mind directly to the brain right away, we could first try to become more objective about experience itself. Right now, the only way we understand experiences is by using our imagination — by trying to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes or by reflecting on our own point of view. That means our understanding of experience is completely tied to empathy and first-person perspective.

Nagel thinks this is a serious limitation. He says we should treat this as a challenge to invent:

- new concepts, and

- new methods

for describing experience in a way that does not depend on imagining what it feels like. He calls this idea an “objective phenomenology” — a way of describing experiences objectively, even for beings who cannot have those experiences themselves.

The goal of such a project would be this:

To describe, at least partly, what experiences are like in terms that could be understood by someone who can never have those experiences.

For example, we might try to develop concepts that could explain what seeing is like to a person who has been blind from birth. Nagel admits that we would eventually hit a limit — some things would still be impossible to convey — but he thinks we could go much further than we can right now, and with much more precision.

He also says that the kinds of sloppy comparisons people currently use — like “red is like the sound of a trumpet” — are not very helpful. Anyone who has both seen red and heard a trumpet knows that these analogies don’t really capture what either experience is like.

However, he thinks that some structural features of experience — such as patterns, organization, relationships between sensations — might be describable in objective terms, even if the raw “feel” itself is partly left out. He also suggests that new kinds of concepts, different from our everyday first-person ones, might even help us understand our own experiences better by giving us some distance from them.

Finally, he connects this proposal back to the mind–body problem.

He says that if we could develop this kind of objective way of describing experience, it might help us ask better, clearer questions about the physical basis of experience. The parts of experience that can be objectively described might be better candidates for scientific explanation in the usual sense.

But even if that optimistic guess turns out to be wrong, he ends with a very firm conclusion:

We are not ready to seriously attempt a complete physical theory of the mind until we have thought much more deeply about the relationship between the subjective and the objective.

Otherwise, we will keep talking past the real problem instead of confronting it.

Core takeaway in one short paragraph

Nagel’s final message is that progress may require inventing an entirely new way of describing experience — one that does not rely on personal imagination or first-person perspective. Such an “objective phenomenology” would try to describe what experiences are like in terms that even a being incapable of having those experiences could understand. This might one day help connect experience to the physical world in a clearer way. But until we develop such tools, Nagel believes that any attempt to fully explain the mind in purely physical terms is premature and risks avoiding the real difficulty instead of solving it.

One thought on “Understanding Nagel”