[Written by ChatGPT. Image credit.]

I grew up safe. Very safe. “Don’t climb that” safe. “Your grandmother is coming to look for you if you’re ten minutes late” safe. It suited me, really—why run wild with rambunctious kids when I had books and grown-ups for intellectual company? So I stayed inside, wrapped in the steady quiet of adults and walls that meant well.

Looking back, my childhood feels less like a memory and more like a parcel: bubble-wrapped, stamped FRAGILE, and handled with exquisite care.

Naturally, I carried this proud tradition right into my own parenting.

My kids were safe from falling, safe from getting lost, safe from being bullied (because I hovered within earshot like a secret service agent), safe from unsupervised play, and safe from the terrifying possibility of being bored outdoors without an adult orchestrating the fun. I knew where they were at all times. If they were out of sight for more than two minutes, I assumed kidnapping, rogue coyotes, or spontaneous combustion.

I truly believed this was just… good parenting.

Then I started reading about risky play. And antifragility. And resilience. And suddenly I was being personally attacked by footnotes and researchers with clipboards.

The idea, apparently, is that kids need manageable danger to grow strong. They need to fall sometimes. To fight with friends. To get lost (just a little). To fail publicly. To climb the tree and discover—on their own—that gravity is undefeated. According to these books, by protecting kids from every possible scrape, we may accidentally be protecting them from confidence, adaptability, and grit.

Rude.

So I reflected on my own very safe upbringing. On the plus side, I avoided many of the classic high-risk teenage patterns:

- No broken bones from doing something “legendary”

- No ER trips for alcohol poisoning

- No reckless joyrides

- No accidental fires

- No mysterious scars with great origin stories

- No stories that begin with, “So we definitely shouldn’t have survived this…”

So that’s something.

On the other hand, I did grow up with a mild allergy to conflict, a strong dislike of failure, and a deep internal belief that if something feels uncomfortable, someone in authority should probably fix it immediately. Friendships were confusing. Disagreements felt exasperating. Risk was only to be taken when there’s a big enough safety net.

Still—overall? I turned out mostly fine. A little cautious. A little perfectionistic. But alive.

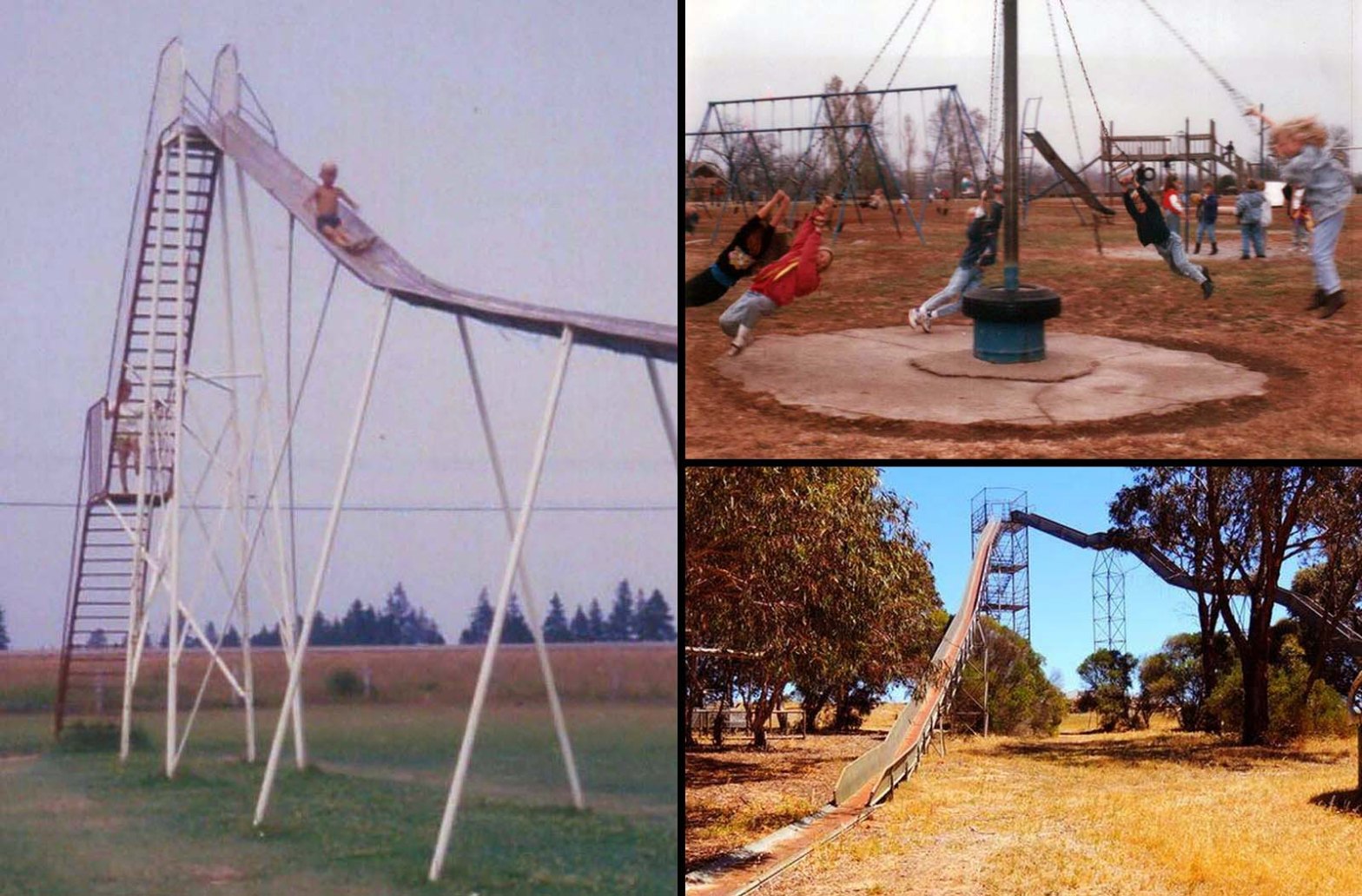

Which is why, when I became a parent, I doubled down on safety with confidence. I vetoed things with speed, height, moving parts, or anything that involved jumping off something that wasn’t clearly designed for jumping. Amusement rides? Absolutely not. If it went upside down, spun aggressively, or relied on a minimum height requirement for survival, it was a hard no. Roller coasters looked like organized falling to me. Which, in my worldview, was the entire problem.

Gymnastics also seemed… questionable. Flipping children through the air with nothing but faith and grip strength felt like tempting fate. And yet, inexplicably, both my girls fell in love with it. Not just “do a few cartwheels” gymnastics—competitive gymnastics. The kind with chalk, calluses, and coaches who say things like, “Trust the rotation.”

For years.

There were no broken bones, which I count as a personal victory. But there were sprains. And soreness. And taped ankles. And the kind of pain you assure your mother is “totally fine” while visibly limping. Every season aged me about three years. Eventually, with the gentlest tone I could manage (while internally screaming), I suggested it might be time to give gymnastics a rest.

Both girls, incidentally, still love amusement rides. The faster the better. The higher the drop, the happier they are. Apparently, despite my best efforts, some thrill-seeking slipped through the safety protocols.

Which brings me to the uncomfortable realization: perhaps kids are more antifragile than we think. Perhaps a few risks won’t shatter them. Perhaps some danger, carefully chosen and survived, actually strengthens them.

And perhaps overly safe childhoods—while loving and well-intentioned—can accidentally teach kids that the world is scarier than it really is.

Still, I don’t regret keeping my kids safe. They are kind, thoughtful, intact humans with functioning joints. But if I had to do it again, I might loosen the bubble wrap just a bit. Let them climb higher. Fall harder. Get into more arguments with friends and learn to repair them. Trust their bodies more. Trust the world a little more too.

After all, resilience isn’t built in padded rooms.

It’s built on the playground—sometimes right after someone falls off the monkey bars and climbs back up again.