[Written by Claude. Cognitive Bias Codex from here. Image credit.]

Related Post: Cognitive Bias #1, Cognitive Bias #2

How evolution built brains that act fast, consequences be damned

Imagine two of your ancestors standing at the edge of a river. A child has fallen in and is being swept downstream.

Ancestor A thinks: “I should gather more information. How deep is the water? What’s the current speed? What’s my exact swimming ability? What are the statistical risks? Let me calculate the optimal intervention strategy.”

Ancestor B thinks: “CHILD DROWNING” and jumps in.

Ancestor A’s genes aren’t in you. Ancestor B’s are.

This single scenario explains why every bias in the “Need to Act Fast” category exists: Evolution didn’t reward perfect decisions. It rewarded fast decisions. More precisely, it rewarded brains that could overcome paralysis and do something when doing nothing meant death.

The Tyranny of Time

Here’s the brutal arithmetic of survival that shaped your brain:

- Fast decision, wrong outcome: You might survive, learn, adjust

- Slow decision, right outcome: You might be too late

- No decision, any outcome: You definitely lose

In the ancestral environment, almost every important decision came with a time limit. The predator is approaching—hide or fight? The food is available—eat now or save for later? The tribe is moving—follow or stay? The stranger approaches—welcome or attack?

Natural selection didn’t give us time to think. It gave us mechanisms to overcome our own hesitation so we could act before the opportunity (or threat) disappeared.

These mechanisms—what we now call biases—weren’t bugs in the system. They were the system. They’re how evolution solved the fundamental problem: how do you get an intelligent, thoughtful brain to do things when thinking takes too long?

The Commitment Problem: Why We Can’t Quit

Let’s start with perhaps the most puzzling category of biases: why do we keep investing in things that clearly aren’t working?

The Sunk Cost Trap

The sunk cost fallacy seems purely irrational. You’ve spent two hours and $50 on a terrible movie. Leaving won’t get your money or time back. Yet you stay because you’ve “invested too much to quit now.”

But consider our ancestors. They spent three days tracking a wounded animal. On day four, the trail grows faint. Should they quit and start over, or keep pursuing?

In the modern world, we say “ignore sunk costs—they’re already gone.” But in the ancestral world, persistence often paid off. The hunting party that gave up easily came home hungry. The one that kept going despite setbacks often succeeded. Resources and opportunities were scarce enough that abandoning a pursuit meant losing everything invested and having to start completely over.

The brain’s solution? Wire in a strong bias toward completion. Make it painful to quit. Make past investment feel meaningful. Make giving up feel like failure.

Was this always optimal? No. Did it work better than constantly giving up and starting over? Absolutely.

The IKEA Effect: Loving Your Labor

The IKEA effect—valuing things more because you made them—seems like pure vanity. But it’s actually a brilliant evolutionary solution to a problem: how do you motivate people to create things when creation is hard?

Our ancestors who spent days crafting a tool needed to value that tool enough to maintain it, protect it, and use it carefully. If they saw their hand-made spear as worthless compared to someone else’s, they’d lack motivation to create anything.

The brain’s solution? Automatically boost the perceived value of things you create. Make your own creations feel special. This wasn’t irrational—it was a motivational hack that kept our ancestors innovating, building, and creating even when it was difficult.

Today, you overvalue the wobbly chair you assembled yourself. But that same mechanism is why humans became the only species that creates complex tools, builds structures, and makes art.

Loss Aversion: Keeping What You Have

Loss aversion—feeling losses more intensely than equivalent gains—is evolution’s way of saying “DON’T DROP THE BALL.”

In the ancestral environment, gains were nice but losses could be catastrophic. Finding extra food was good. Losing your stored food meant starvation. Making a new friend was valuable. Losing an ally could get you killed. Gaining territory expanded options. Losing territory could mean death.

The asymmetry was real: the pain of loss needed to be stronger than the pleasure of gain because losses threatened survival more than gains enhanced it.

Your ancestors who felt “meh” about losing their spear but “yay!” about finding a new one ended up defenseless. Your ancestors who clutched their spear desperately and felt devastated when they lost it kept their tools and survived.

Today, you feel more upset about losing $100 than happy about finding $100. This seems irrational in a world of abundance, but it’s your brain using a calculator calibrated for a world of scarcity.

The Immediacy Bias: Now or Never

Why do we favor immediate rewards over delayed ones so dramatically?

Hyperbolic Discounting

Hyperbolic discounting—valuing immediate rewards disproportionately—exists because for most of evolutionary history, the future was profoundly uncertain.

If food is available now, you eat it now. Why? Because:

- You might not be alive tomorrow to eat it

- Someone else might take it

- It might spoil

- The opportunity might not return

A bird in the hand was genuinely worth several in the bush because the bush might be empty when you got there, or you might be dead, or the birds might fly away.

Your ancestor who chose the certain berry in front of them over the hypothetical larger harvest tomorrow survived famines, droughts, and unpredictable environments. The one who deferred gratification for a future that never came starved while waiting.

The Identifiable Victim Effect

The identifiable victim effect—caring more about one identified person than thousands of anonymous people—isn’t moral failure. It’s evolutionary mathematics.

In a tribe of 50-150 people, every individual mattered immensely. Losing one person was a 1-2% reduction in group strength, genetic diversity, and knowledge. You couldn’t afford to think statistically. You had to care intensely about each identifiable member.

Moreover, helping one person right in front of you had immediate, visible results. You could see them survive, they’d remember your help, reciprocity was direct and certain. Helping anonymous thousands? Our ancestors never faced that scenario. There was no psychological infrastructure for it.

Today, we’re moved to donate thousands to save one named child while ignoring millions dying from preventable diseases. Our brains are using tribal-scale empathy in a global-scale world.

The Confidence Engine: Believing You Can

Here’s a strange fact: the most successful humans weren’t the most accurate assessors of their abilities. They were the optimistic ones who slightly overestimated what they could do.

The Optimism Bias

Optimism bias—believing you’re more likely to succeed and less likely to suffer than you actually are—seems like self-delusion. But it was motivational fuel.

Imagine two hunters:

- Realistic Rick: “Hunting is dangerous. I’ll probably fail. I might get injured. The odds aren’t good.”

- Optimistic Olga: “I’m a great hunter. Today’s the day. I can do this.”

Rick stays in camp, conserves energy, and slowly starves. Olga goes hunting, fails most days, but occasionally succeeds—and that occasional success keeps her alive.

The person who accurately assessed that most attempts fail wouldn’t attempt anything. The person who slightly overestimated their chances kept trying until they succeeded.

Optimism wasn’t about being right. It was about being motivated.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect—incompetent people overestimating their ability—seems like pure arrogance. But consider: how do you get someone to try something they’ve never done before?

If beginners accurately assessed their incompetence, they’d never attempt anything new. The novice hunter who truly understood how bad they were at hunting would never hunt. The first-time tool maker who grasped their cluelessness would never make tools.

Evolution’s solution? Give beginners enough confidence to try despite their incompetence. Make them slightly delusional about their abilities so they’ll attempt things, fail, learn, and eventually become competent.

The overconfident beginner tries, fails, and learns. The accurately self-assessed beginner never starts. The first one eventually develops skills. The second one doesn’t.

Yes, this means incompetent people annoy you with their unwarranted confidence. But it also means humanity kept attempting new things despite having no idea how to do them.

The Illusion of Control

The illusion of control—believing we can influence random events—kept people engaged with the world.

If your ancestors truly accepted that hunting success was mostly random, that weather was unpredictable, that illness struck arbitrarily, they’d become passive and fatalistic. Why perform rituals before the hunt if outcome is random? Why try to predict weather if it’s chaotic? Why care for sick people if recovery is chance?

But here’s the thing: the world wasn’t entirely random. Skill did matter. Preparation helped. Knowledge improved outcomes. The problem was distinguishing what you could control from what you couldn’t.

Evolution’s solution? Err on the side of assuming control. Make people believe their actions matter more than they actually do. Better to perform useless rituals while also doing genuinely useful preparation than to do nothing because you can’t tell which is which.

The gambler blowing on dice before rolling looks foolish. But that same mechanism is why humans kept refining hunting techniques, improving tool designs, and developing agriculture—believing their efforts mattered, even when early results were mostly noise.

The Autonomy Imperative: Don’t Fence Me In

A fascinating category of biases exists solely to preserve your freedom of choice.

Reactance: The Psychology of Rebellion

Reactance—resisting when your freedom is threatened—seems childish. Tell someone they can’t do something, and they immediately want to do it.

But in tribal environments, autonomy was survival. Being controlled by others meant:

- Loss of mate choice (genetic dead end)

- Loss of resource access (starvation risk)

- Loss of mobility (trapped in dangerous areas)

- Loss of decision-making (forced into lethal choices)

The person who accepted control too easily became a tool of others’ strategies. The person who fought for autonomy maintained the ability to make survival-critical decisions.

Your brain’s fierce protection of autonomy—even when it’s counterproductive—is evolution saying “nobody owns you.” This was life-or-death serious for most of human history.

Status Quo Bias: If It Ain’t Broke

Status quo bias—preferring things to stay the same—seems like pure conservatism. But it’s actually sophisticated risk management.

Every change is a gamble. The current situation might not be perfect, but you’re alive. You’ve figured out how to survive these circumstances. Change means uncertainty, new risks, and unknown problems.

For our ancestors, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” was wisdom. The current camp location has reliable water—moving might find better water or might find drought. The current leadership is mediocre—new leadership might be better or might be catastrophically worse. The current food sources are adequate—trying new plants might discover nutrition or poison.

The bias toward maintaining the status quo wasn’t laziness. It was caution born from experience that change often made things worse in a world where “worse” could mean death.

Today, we stick with suboptimal jobs, relationships, and habits because our brains are wired to fear change. The irony? In our modern world of abundance and safety nets, change is usually far less risky than our brains assume.

The Simplicity Preference: Good Enough, Fast Enough

Why do we prefer simple explanations and avoid ambiguity?

Occam’s Razor: Simpler is Usually Right

Occam’s razor—preferring simpler explanations—wasn’t philosophical elegance. It was computational efficiency.

Your ancestor hears rustling in the bushes. Possible explanations:

- Wind

- Small animal

- Large predator

- Alien spacecraft

- Ghost

- Elaborate prank by tribe members

The simplest explanation (wind or small animal) is usually right. Making decisions quickly required assuming the simplest explanation first, then escalating only if evidence demanded it.

Considering all possibilities every time wasn’t wisdom—it was paralysis. The brain that immediately jumped to “probably wind” and moved on could make hundreds of decisions daily. The brain that considered every possibility for every rustling leaf never got anything done.

Ambiguity Bias: Known Risks Beat Unknown Risks

Ambiguity bias—preferring known risks over unknown ones—exists because your ancestors had experience with known risks.

They knew how to handle the predators in their territory. They knew which plants in their area were safe. They knew the social dynamics of their tribe. These were known risks with proven survival strategies.

Unknown risks? No proven strategies. No knowledge base. No experience. Unknown risks killed people in surprising ways.

“Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t” wasn’t pessimism—it was the recognition that experience and knowledge were survival advantages. The familiar danger you’d survived before was genuinely safer than the unfamiliar danger you’d never encountered.

The Conjunction Fallacy: Detailed Feels Right

The conjunction fallacy—thinking specific scenarios are more probable than general ones—exists because specific scenarios activate memory and imagination more effectively.

“Linda is a bank teller” is abstract and hard to imagine. “Linda is a bank teller active in feminist causes” is vivid and creates a mental image. Your brain uses vivid mental images to evaluate probability (another shortcut), so the detailed version feels more real, hence more likely.

This seems irrational until you consider: in the ancestral world, the scenarios you could imagine in detail were usually based on things you’d actually seen or heard about. If you could vividly imagine a specific scenario, it was probably because similar things had happened.

Today, we’re exposed to thousands of fictional scenarios (movies, books, news) that we can imagine vividly but which are actually rare. Our brains weren’t built for this information environment.

The Attribution Machine: Protecting Your Self-Concept

Why do we take credit for success but blame circumstances for failure?

The Self-Serving Bias

Self-serving bias—attributing success to yourself and failure to circumstances—maintained the confidence necessary for repeated attempts.

If you attributed every failure to your own incompetence, you’d become demoralized and stop trying. If you attributed every success to luck, you’d lack confidence in your abilities.

Evolution needed humans who:

- Learned from failures (acknowledged what went wrong)

- But didn’t become depressed (protected self-esteem)

- Built on successes (recognized what they did right)

- But stayed motivated to improve (didn’t become complacent)

The self-serving bias achieved this impossible balance. When you failed, attributing it to external factors (“bad luck,” “unfair circumstances”) protected your confidence to try again. When you succeeded, taking credit built the self-efficacy needed to attempt harder challenges.

Yes, this makes you annoying at parties when you blame traffic for being late while taking credit for arriving early. But it also kept your ancestors attempting dangerous hunts after failures and trying complex tool-making after setbacks.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

Fundamental attribution error—attributing others’ behavior to personality and your own to circumstances—served social navigation.

When evaluating others, you need to predict future behavior. If someone acts aggressively, assuming “they’re an aggressive person” lets you avoid them in the future. If you assume “they had a bad day,” you can’t predict whether they’ll be aggressive tomorrow.

Stable personality attributions for others enable social strategy. You can categorize people (trustworthy, dangerous, generous, selfish) and make decisions about who to approach, avoid, cooperate with, or compete against.

But for yourself, you need flexibility. Seeing your own behavior as circumstantially driven lets you:

- Forgive yourself for mistakes (maintaining motivation)

- Adapt to different situations (being aggressive when needed, cooperative when beneficial)

- Avoid being locked into one self-definition

The double standard wasn’t hypocrisy. It was a sophisticated solution to different problems: predicting others vs. motivating yourself.

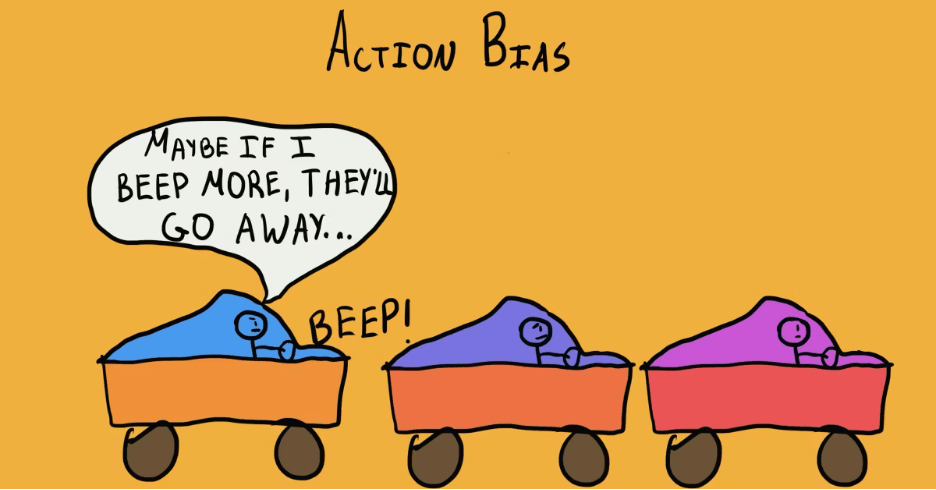

The Modern Trap: Stone Age Urgency Meets Information Age Complexity

Here’s what makes the “Need to Act Fast” biases particularly problematic today: we’re using emergency decision-making systems for non-emergency decisions.

Your brain’s action biases evolved for scenarios like:

- Physical danger (act now or die)

- Resource competition (grab it or lose it)

- Social dynamics (respond now or lose status)

- Immediate survival (food, shelter, safety)

These scenarios genuinely required fast action. Hesitation was fatal. These biases were calibrated for a world where:

- Most decisions had immediate, visible consequences

- Reversing decisions was difficult or impossible

- Information gathering took time you didn’t have

- Inaction was often the worst option

Today’s important decisions are different:

- Career choices (reversible, long-term consequences)

- Financial decisions (complex, probabilistic outcomes)

- Relationship commitments (require deliberation)

- Political choices (nuanced, far-reaching implications)

These decisions benefit from slow, careful thinking. But your brain still screams “ACT NOW!” because it’s running software designed for escaping leopards, not choosing retirement funds.

Living With an Action-Biased Brain

Understanding why these biases exist doesn’t eliminate them, but it suggests a crucial insight: your brain’s bias toward action was right for most of human history.

The person who acted confidently despite uncertainty succeeded more often than the person who waited for perfect information. The person who persisted despite setbacks achieved more than the person who quit easily. The person who valued their autonomy maintained better life outcomes than the person who accepted control.

The problem isn’t the biases themselves. The problem is context mismatch. Your brain is using emergency protocols for non-emergencies, applying hunter-gatherer decision-making to information-age choices, and treating reversible decisions as life-or-death.

The solution isn’t to eliminate your action bias—you need it for many situations. The solution is to recognize which decisions are genuinely urgent (house on fire, child in danger, time-sensitive opportunity) and which merely feel urgent because your brain defaults to “act fast” mode.

The Gift of Bias

Here’s the profound truth: These “biases” are why humans became the dominant species on Earth.

The confidence to attempt the impossible. The persistence to continue despite failure. The commitment to see things through. The preference for action over paralysis. The protection of autonomy and dignity. The ability to make fast decisions with incomplete information.

These weren’t bugs. They were humanity’s competitive advantage.

Yes, they make you overconfident. Yes, they make you throw good money after bad. Yes, they make you resist change and oversimplify complexity. But they also make you try new things, persist through difficulty, stand up for yourself, and actually do something instead of thinking forever.

The challenge of modern life isn’t to eliminate these biases. It’s to recognize when your brain is shouting “ACT NOW!” whether you need to act now or not—and to have the wisdom to know the difference.

The next time you feel an urgent compulsion to do something right now, ask yourself: “Is this genuinely urgent, or does it just feel urgent because my brain is designed to favor action over thought?” Sometimes the answer is “genuinely urgent” and you should trust your instincts. Sometimes the answer is “just feels urgent” and you should slow down. Learning to tell the difference might be the most valuable skill for a brain built for the savanna trying to navigate the modern world.

3. NEED TO ACT FAST

To stay focused, we favor the immediate, relatable thing in front of us:

- Hyperbolic discounting – We value immediate rewards disproportionately more than future rewards, even when the future reward is objectively better. You choose $50 today over $100 in a year, even though waiting would double your money, because the immediate reward feels much more real and valuable.

- Appeal to novelty – We assume that newer ideas, products, or approaches are automatically better than older ones. Companies market products as “new and improved” because we’re drawn to novelty, even when the “improvement” is trivial or the old version worked perfectly well.

- Identifiable victim effect – We’re more motivated to help a single, identified person than to help a larger group of anonymous people, even if helping the group would save more lives. Millions donate to save one child trapped in a well while ignoring statistics about thousands of children dying from preventable diseases daily.

To get things done, we tend to complete things we’ve invested time & energy in:

- Sunk cost fallacy – We continue investing in something because we’ve already invested in it, even when abandoning it would be more rational. You sit through a terrible movie because you paid $15 for the ticket, even though those two hours of your life are worth more than $15.

- Irrational escalation – We increase commitment to a failing course of action to justify previous investments. A company pours more money into a failing product line because admitting failure would mean acknowledging the initial investment was a mistake.

- Escalation of commitment – This is another term for irrational escalation, where we commit more resources to a decision based on prior commitments rather than current evidence. Governments continue funding unsuccessful programs because stopping would mean admitting the previous years of funding were wasted.

- Loss aversion – We feel the pain of losing something about twice as strongly as the pleasure of gaining the same thing. You’d be much more upset about losing $100 than you’d be happy about finding $100, making you avoid risks even when they’re statistically favorable.

- IKEA effect – We value things more highly when we’ve put effort into creating them. The wobbly bookshelf you assembled yourself seems more valuable and attractive than a sturdier store-bought one because you invested labor in it.

- Processing difficulty effect – We remember information better when it requires more effort to process, and sometimes assume that difficult-to-process information is more valuable. A wine described in complex, flowery language seems more sophisticated than one with a simple description, even if they taste identical.

- Generation effect – We remember information better when we generate it ourselves rather than simply reading it. Students who write their own study notes remember material better than those who just read the textbook, even if the textbook is more accurate.

- Zero-risk bias – We prefer options that eliminate risk entirely over options that reduce larger risks by a greater amount. People pay more to reduce a risk from 1% to 0% than from 10% to 5%, even though the second reduction saves more lives.

- Disposition effect – We’re more likely to sell assets that have increased in value (locking in gains) while holding assets that have decreased in value (avoiding losses). Investors sell winning stocks too early and hold losing stocks too long, hoping they’ll recover.

- Unit bias – We tend to consume an entire unit of something, regardless of its size, believing one unit is the appropriate amount. You eat the entire restaurant portion even when it’s far more food than you need, simply because it’s presented as “one serving.”

- Pseudocertainty effect – We perceive outcomes as certain when they’re actually uncertain if the framing suggests certainty. Choosing a guaranteed $30 refund over a 50% chance at a $100 refund feels safe, even though the second option is worth more on average.

- Endowment effect – We value things more simply because we own them. You wouldn’t pay $50 for a coffee mug, but once someone gives you that mug, you wouldn’t sell it for less than $50.

- Backfire effect – When our beliefs are challenged with evidence, we sometimes believe them even more strongly rather than updating our views. Showing anti-vaccine parents scientific evidence that vaccines are safe can actually strengthen their anti-vaccine beliefs.

To avoid mistakes, we aim to preserve autonomy and group status, and avoid irreversible decisions:

- System justification – We defend and bolster existing social, economic, and political systems, even when they work against our interests. Poor people sometimes defend inequality and oppose redistribution because justifying the current system feels psychologically necessary.

- Reverse psychology – We have an urge to do the opposite of what we’re told when we feel our freedom is threatened. Tell a teenager they absolutely cannot go to a party, and they become determined to attend, even if they weren’t interested before.

- Reactance – We experience an unpleasant motivational arousal when our freedom of choice is threatened, leading us to resist or do the opposite. When a government mandates something, people resist simply because they dislike being told what to do, even if they’d voluntarily choose the same action.

- Decoy effect – Our preference between two options changes when a third, asymmetrically dominated option is introduced. A theater offers popcorn: small for $3, large for $7. Add a medium for $6.50, and suddenly the large seems like a great deal, increasing large sales dramatically.

- Social comparison bias – We favor hiring, working with, or promoting people who are less competent than us to avoid threatening our own status. A manager might prefer to hire less talented subordinates to ensure they remain the smartest person in the room.

- Status quo bias – We prefer things to stay the same; changes from the baseline are perceived as losses. Employees stick with default retirement plan options even when switching would benefit them, simply because the default requires no decision.

To act, we must be confident we can make an impact and feel what we do is important:

- Overconfidence effect – We have excessive confidence in our own abilities, knowledge, and predictions. Most drivers rate themselves as above average, which is statistically impossible, and most entrepreneurs believe their business will succeed despite high failure rates.

- Egocentric bias – We rely too heavily on our own perspective and have difficulty seeing things from others’ viewpoints. During arguments, both people often believe they contributed more to the relationship, listened more, and were more reasonable.

- Optimism bias – We believe we’re less likely than others to experience negative events and more likely to experience positive ones. People think they’re less likely than average to get divorced, have a car accident, or develop cancer, even though these events are common.

- Social desirability bias – We present ourselves in a favorable light, especially in surveys and self-reports. People under-report socially undesirable behaviors (drinking, drug use, prejudice) and over-report desirable ones (voting, charitable giving, exercise).

- Third-person effect – We believe media messages have a greater effect on others than on ourselves. You think advertisements manipulate other people but not you, and propaganda affects others but you see through it.

- Forer effect – We believe vague, general personality descriptions specifically apply to us. Reading a horoscope with statements like “you have a need for others to like you” feels personally accurate, even though it applies to nearly everyone.

- Barnum effect – This is another name for the Forer effect, where we accept vague and general personality descriptions as uniquely applicable to ourselves. Psychic readings feel accurate because they use statements general enough to apply to anyone.

- Illusion of control – We overestimate our ability to control events that are actually determined by chance. Gamblers throw dice harder for high numbers and softer for low numbers, as if their throwing force influences the outcome.

- False consensus effect – We overestimate how much others share our beliefs, values, and behaviors. If you support a political candidate, you’ll likely overestimate their actual popularity, surprised when they lose.

- Dunning-Kruger effect – People with low ability at a task overestimate their ability, while experts underestimate theirs. Someone who’s watched a few medical TV shows might feel confident diagnosing illnesses, while actual doctors recognize how much they don’t know.

- Hard-easy effect – We overestimate our likelihood of success on difficult tasks and underestimate it on easy tasks. Before a difficult exam, students feel oddly confident, while before an easy one, they worry more.

- Lake Wobegon effect – We believe we’re above average on most dimensions, named after the fictional town where “all the children are above average.” Most people rate themselves as above-average drivers, leaders, and friends, which is mathematically impossible.

- Self-serving bias – We attribute successes to our own abilities and efforts while blaming failures on external circumstances. When you ace a test, it’s because you’re smart; when you fail, the test was unfair or you had a bad day.

- Actor-observer bias – We attribute our own behavior to situational factors while attributing others’ behavior to their personality. You’re late because traffic was bad; your colleague is late because they’re irresponsible.

- Fundamental attribution error – We overemphasize personality-based explanations for others’ behavior while underemphasizing situational factors. Seeing someone yell at a cashier, we think they’re a jerk, not considering they might have just received devastating news.

- Defensive attribution hypothesis – We blame victims for their misfortune to maintain our belief that the world is fair and that bad things won’t happen to us. When someone is robbed, we think “they shouldn’t have been walking there” rather than acknowledging that anyone could be randomly victimized.

- Trait ascription bias – We view ourselves as relatively varied in personality and behavior while seeing others as predictable and consistent. You see yourself as sometimes outgoing and sometimes shy depending on context, but view your colleague as “just a shy person.”

- Effort justification – We value outcomes more when we’ve expended significant effort to achieve them, even if the outcome is identical to one requiring less effort. A meal tastes better after spending hours cooking it, and an accomplishment feels more meaningful if it was difficult.

- Risk compensation – We adjust our behavior in response to perceived safety measures, often negating their benefit. Drivers with anti-lock brakes drive more aggressively, and people who wear helmets take more risks while skiing.

- Peltzman effect – This is another term for risk compensation, specifically referring to how safety regulations can lead to riskier behavior that partially offsets the safety benefit. Mandatory seatbelt laws led some drivers to drive faster, feeling protected.

We favor simple-looking options and complete information over complex, ambiguous options:

- Ambiguity bias – We prefer known risks over unknown risks, even when the unknown option might be better. You’d rather bet on a coin flip (50% known probability) than on a sports game where you don’t know the odds, even if research suggests the game offers better chances.

- Information bias – We seek information even when it cannot affect our decision, believing more information is always better. Patients want every medical test available even when their doctor explains the tests won’t change the treatment plan.

- Belief bias – We judge arguments based on the believability of their conclusions rather than on logical validity. If an argument reaches a conclusion you agree with, you’re less likely to notice that the reasoning was flawed.

- Rhyme as reason effect – We perceive statements that rhyme as more truthful and accurate than statements that don’t. “An apple a day keeps the doctor away” seems wiser than “eating apples regularly promotes health,” even though they mean the same thing.

- Bike-shedding effect – We give disproportionate weight to trivial issues while avoiding complex, important ones. A committee spends hours debating the color of a bike shed but quickly approves a multi-million dollar nuclear plant because the shed is easier to understand.

- Law of Triviality – This is another name for the bike-shedding effect, where we focus on trivial matters because they’re easier to grasp. Teams spend entire meetings discussing the lunch menu while rushing through critical budget decisions.

- Delmore effect – We judge solutions as better when they’re expressed in complicated language or technical jargon. A simple marketing strategy sounds more impressive when described using business buzzwords and complex frameworks.

- Conjunction fallacy – We judge specific, detailed scenarios as more probable than general ones, even though adding details always makes something less likely. “Linda is a bank teller active in feminist causes” seems more probable than “Linda is a bank teller,” though the second includes all possibilities of the first.

- Occam’s razor – We prefer simpler explanations over complex ones, assuming the explanation with the fewest assumptions is most likely correct. Hearing hoofbeats, we think horses not zebras—a useful heuristic though sometimes the complex explanation is actually right.

- Less-is-better effect – We prefer a smaller set that looks complete over a larger set that looks incomplete. People pay more for 24 pieces of fine china (a complete set) than for 40 pieces that include the 24 plus 16 mismatched pieces, even though the second option includes everything in the first plus extras.