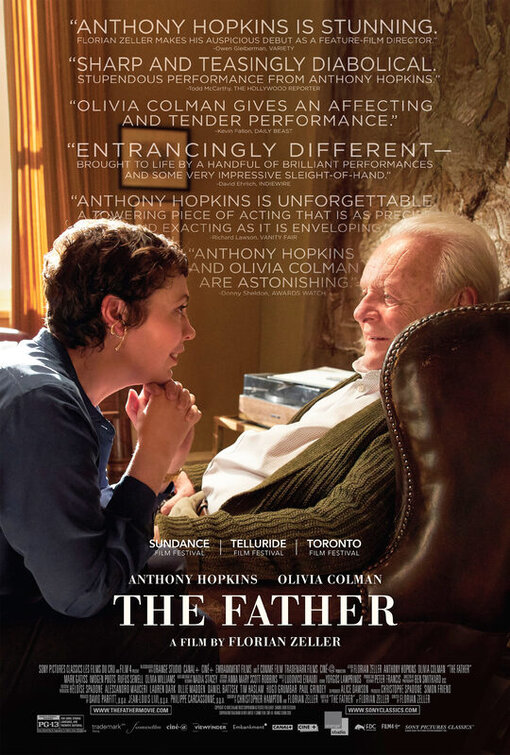

I’ve been thinking a lot about memory lately. Sadly, my grandmother, who is over 90, no longer recognizes me. Just last year, she could recall a few stories from my childhood and share them with affection every time we spoke on the phone. Now, those memories have vanished, and to her, I’m just another stranger. I often wonder if life has become more confusing for her, with new, unfamiliar faces appearing every day. It’s reminiscent of Anthony in “The Father,” where the very fabric of reality shifts incessantly, leaving him bewildered.

This raises the question: does memory loss alter a person’s identity? In my grandmother’s case, it seems her sense of self remains, but she can no longer recognize her family or form new memories. I wonder if, in the future, repairing neurons might allow for the continuation or even restoration of these precious memories.

Related posts: brain replicas, cyborgs, hallmarks of aging.

[Written by Grok]

The relationship between memory, identity, and the continuity of self is indeed philosophically and neuroscientifically intriguing. Here’s how these concepts relate:

Memory and Identity:

- Continuity of Memory: Identity is often thought to rely on a continuity of memory. If memories are not continuous or reliable, one’s sense of self might be questioned or altered. This is because:

- Narrative Identity: Our personal identity is constructed through the stories we tell about our lives, which are based on our memories. If these memories are fragmented or altered, the narrative changes, potentially leading to a different sense of identity.

- Neuroscientific Perspective:

- Neuronal Plasticity: Brains continuously change. Neurons die and new connections form, which might mean that even if memories exist, their context or emotional significance can shift, subtly changing identity over time.

- Pathological Examples:

- Conditions like amnesia or Alzheimer’s show how memory loss can lead to a profound change or loss of identity, where individuals no longer recognize themselves or their past.

The Ship of Theseus Analogy:

- Identity Over Time: The paradox asks if replacing all parts of an object over time still makes it the same object. In the context of identity:

- Gradual Change: If changes are gradual, like replacing one neuron or plank at a time, there might be an intuitive sense that identity remains intact because the change is imperceptible or feels continuous.

- Philosophical Views:

- Locke’s Memory Theory: John Locke argued that personal identity is preserved through memory; if all memories (and by extension, all neurons related to these memories) are preserved or replaced in a way that maintains continuity, then identity could be seen as intact.

- Bundle Theory (Hume): Suggests that the self is not a single enduring entity but a bundle of perceptions or memories. Here, identity might be seen as a process rather than a substance, allowing for changes in components as long as the process continues.

Neuronal Repair and Identity:

- Repair vs. Replacement:

- If neurons are repaired rather than replaced, one might argue that identity is more likely to remain intact because the original cells, with their unique connections, are maintained or restored.

- However, if neurons are replaced, even one at a time, the question becomes whether the new neuron can carry the same memories or if it merely replicates function without the original context.

- Functional Equivalence:

- If new neurons can functionally replicate the role of old ones with the same memories, connections, and emotional significance, then identity might be preserved. But this assumes an exact replication, which is challenging given the complexity of neural networks.

- Philosophical Implications:

- Psychological Continuity: If psychological continuity (which includes memories, personality traits, and consciousness) is maintained through neuron repair or replacement, identity might be argued to remain intact. However, this depends on how one defines “identity” – whether it’s about continuity of substance or continuity of function.

Conclusion:

- Identity as Process: Identity might be better understood not as a static thing but as a dynamic process or narrative that can adapt to changes as long as there’s some form of continuity or coherence in one’s self-perception and social interactions.

- Ship of Theseus in Neuroscience: Just as the ship might be considered the same despite all parts being replaced if its form and function are unchanged, a person might retain identity if the essence of their memories, beliefs, and relationships remain coherent over time, even if the physical substrate (neurons) changes.

This discussion highlights that while memory and the physical brain are crucial to identity, identity might also encompass more than just biological continuity, involving social, psychological, and narrative elements that persist or adapt through changes.

Forever Young?

The Ship of Theseus:

The Ship of Theseus, also known as the Theseus Paradox or the Syn ship, is a thought experiment from ancient philosophy that poses questions about identity and continuity over time. The basic story is this:

- The Legend: The ship in which Theseus returned from Crete was preserved by the Athenians. As the planks of the ship decayed over time, they were replaced one by one until, eventually, all the original wood had been substituted. The question then arises: is the ship still the same ship as when Theseus sailed it?

- Philosophical Inquiry:

- Identity Over Time: If every part of an object is replaced, does it retain its original identity?

- Constitution vs. Identity: Is the identity of an object tied to its material constitution or to its form, function, or history?

Relation to Anti-Aging:

The Ship of Theseus relates to anti-aging in several thought-provoking ways:

- Biological Replacement:

- Cellular Turnover: Just like the planks of the ship, our bodies continuously replace cells throughout our lives. Some cells, like those in the skin or blood, are replaced frequently, while others, like neurons, less so. If we could accelerate or perfect this process, keeping all cells young and functional, would we remain the “same” person?

- Identity and Aging:

- Continuity of Self: Anti-aging might involve replacing or repairing parts of the body (organs, tissues, cells) to maintain health and youth. But if we replace too much, do we lose our identity? If every cell in your body is new, are you still you?

- Functional vs. Substantive Identity:

- Functionality: If anti-aging technologies focus on maintaining or restoring function rather than preserving the exact material of our bodies, we might argue that identity persists as long as the person’s roles, memories, and capabilities remain consistent.

- Substance: However, if we cling to the idea that identity is tied to the original “stuff” (like the wood of Theseus’s ship), then anti-aging might be seen as creating a new person, not merely preserving the old one.

- Neurological Implications:

- Neurons and Memory: If we extend the metaphor to neurons and memories, anti-aging could involve repairing or replacing brain cells. If memories are what give us our sense of identity, repairing or replacing neurons could theoretically preserve or even enhance identity, but it also poses the question of whether those new neurons are “you” or just a functional duplicate.

- Ethical and Philosophical Questions:

- Authenticity of Life: If we could live indefinitely through replacements or repairs, what would that mean for the authenticity of our existence? Would life feel the same if every part of us was periodically new?

- Identity Over Lifespan: If identity is seen as a narrative or process, perhaps anti-aging would just be another chapter in an extended story of self, where the plot (life experiences) continues regardless of the changing cast (cells).

- The Paradox in Practice:

- Gradual Change: Like the gradual replacement of the ship’s planks, anti-aging might involve such slow and subtle changes that at no point would we feel like a different person, maintaining a sense of continuity despite profound biological transformation.

In essence, the Ship of Theseus serves as a metaphor for considering how we might define “self” or “identity” in the context of anti-aging. It challenges us to ponder whether identity is about the continuity of substance, function, memory, or something else entirely. As anti-aging research progresses, these philosophical questions will become increasingly relevant, pushing us to redefine what it means to grow old or remain “young.”