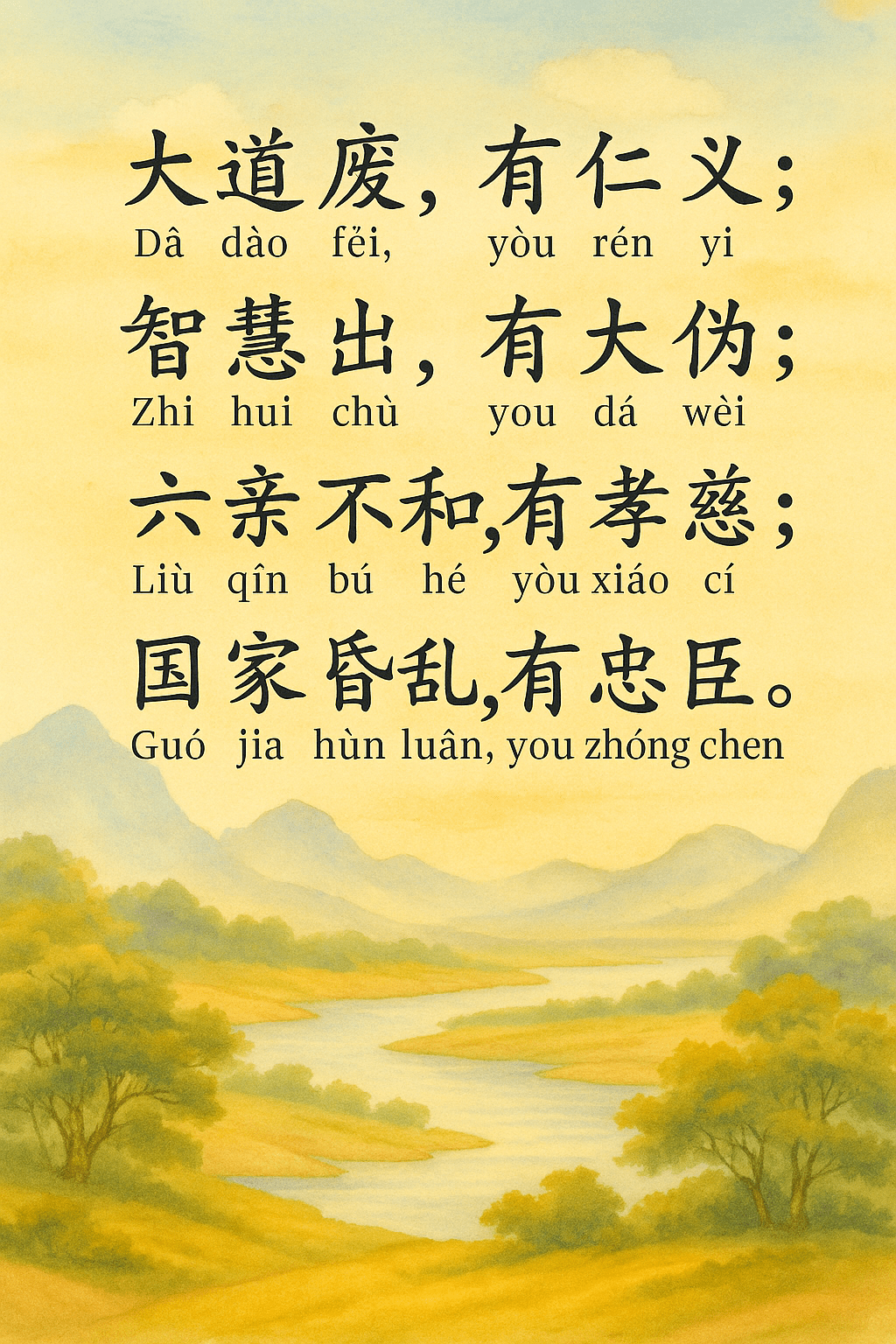

Verse 18 by Lao Zi: 大道废,有仁义;智慧出,有大伪;六亲不和,有孝慈;国家昏乱,有忠臣.

When the Great Way is abandoned, there is benevolence and righteousness.

When wisdom appears, great hypocrisy arises.

When family relationships fall out of harmony, there is talk of filial piety and parental love.

When the state is in chaos, loyal ministers appear.

[Written by ChatGPT]

What if our highest ideals — kindness, wisdom, loyalty — were not signs of a good society, but symptoms of its decline?

That’s the radical message Laozi delivers in Chapter 18 of the Dao De Jing. In this brief but powerful verse, he flips conventional morality on its head. Instead of celebrating righteousness, cleverness, and filial duty as virtues to aspire to, he treats them as symptoms of a world that has strayed from its natural path.

According to Laozi, when the Dao — the “Great Way” of natural balance — is intact, these concepts are unnecessary.

1. “When the Great Way is abandoned, there is benevolence and righteousness.”

When people live in accordance with the Dao — simple, honest, and aligned with nature — they don’t need rules about being “good.” But when that alignment is lost, society compensates with codes of conduct and moral preaching. In other words, the louder the cries for righteousness (yi) and benevolence (ren), the more deeply we’ve lost our way.

We see this today when ethics are loudly proclaimed in politics or corporate mission statements — not because virtue is abundant, but because it is absent and must be manufactured.

2. “When wisdom appears, great hypocrisy arises.”

Here, Laozi warns against cleverness masquerading as virtue. When people pride themselves on being wise, strategic, or intellectually superior, they may also become manipulative or deceitful. True wisdom, in the Daoist view, is silent, intuitive, and humble — not flashy or boastful.

Modern relevance? The rise of “thought leadership” and constant displays of expertise on social media often coincide with performative intelligence and shallow virtue signaling.

3. “When family relationships fall out of harmony, there is talk of filial piety and parental love.”

In traditional Chinese society, the six key relationships — including between parent and child, elder and younger sibling, husband and wife — formed the backbone of order. Laozi suggests that when these relationships break down, society scrambles to restore them through rules and slogans about xiao (filial piety) and ci (parental compassion).

We’ve all seen versions of this: families that proclaim love and loyalty while privately fractured; institutions that emphasize “family values” most when those values are eroding.

4. “When the state is in chaos, loyal ministers appear.”

This line is both ironic and insightful. In times of political decline, those who are called “loyal” are often simply trying to preserve what little order remains. The very appearance of loyalty as a badge of honor implies that betrayal, instability, and conflict are already widespread.

It reminds us that true stability is quiet — when leadership is healthy, loyalty doesn’t need to be shouted from rooftops.

So What Does This Mean for Us?

Laozi isn’t anti-morality. He’s anti-artificial morality.

His point is not that benevolence, wisdom, or loyalty are bad — but that their forced appearance often signals something deeper has been lost. When people must be told to be kind, clever, or obedient, it’s a sign that society is out of alignment with its natural rhythms.

In Daoism, the goal is not to perform virtue, but to live simply and harmoniously, in tune with the deeper order of things.

Key Takeaways for Modern Life

- Don’t confuse loud virtue with real goodness. Often, the best people don’t advertise their values — they live them.

- Watch for overcorrection. When systems collapse, society scrambles to fix the symptoms instead of addressing root causes.

- Return to simplicity. Authenticity doesn’t need ornament. Laozi invites us to restore inner and outer harmony by living with less noise, less cleverness, and more stillness.

Final Thought:

The Dao De Jing doesn’t ask us to do more. It asks us to undo — to shed the posturing, the overthinking, the slogans — and return to what is natural, whole, and quietly powerful.

Because when the Dao is present, no one needs to talk about virtue.

They just live it.

One thought on “The Surface of Virtue vs. the Substance of Harmony”